I recently wrote about an analysis of Michigan’s education system that concluded that charter schools—contrary to what some of their backers claim—spend more on administrative costs, and less on instruction, than traditional public schools.

But you didn’t really think that would be the final word on the subject, did you?

This week, a consultant writing for a charter school association takes issue with that claim, put forward in a study released by the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education. In a blog post written for the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, Larry Maloney argues that the authors’ research does not present a true comparison of administrative spending in charters and traditional publics, particularly in urban areas, such as charter school-rich Detroit.

The debate matters, because it speaks to one of the critical questions about charter schools—whether they do a better job of cutting through the so-called educational bureaucracy and administrative clutter in schools and direct more money to the classroom, where presumably it would have a greater impact on instruction. Many charter school backers say such schools can—and often do—act as efficient models for delivering education, while others say those claims are overblown.

Maloney, the president of Aspire Consulting, LLC, says that spending patterns for charters and traditional publics in urban areas tend to differ significantly from states as a whole. Detroit charters, for instance, receive less funding than traditional district schools. In fiscal 2011, for instance, Detroit public schools averaged 14 percent more in per-pupil revenue than charters, says Maloney. But when it comes to per-pupil spending on instruction, Detroit charters are spending more of the dollars available to them than traditional publics do, writes Maloney. That’s consistent, he says, with patterns across other cities.

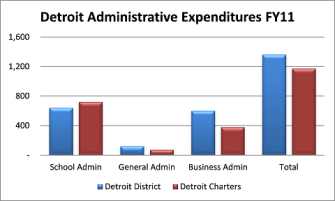

It’s true that charters do outspend traditional publics on administrative costs—$722 per-pupil for charters, to $641 for traditional publics—but only when costs are measured a certain way, Maloney argues. He explains that urban charters must pay relatively high wages to attract talented administrators, and, if those schools have fewer students over which to spread that cost, a per-pupil analysis will show that they have higher administative expenses. But when it comes to other administrative cost categories, such as general administration or business administration, Detroit schools log lower costs than traditional publics, the author concludes. (See the chart, below.) Aspire Consulting is based in Washington, D.C., and its clients include foundations, think tanks, and universities. It is neutral on charters, specifically. It has conducted research on charter school funding for the pro-charter Thomas B. Fordham Institute, among others, and is currently analyzing spending on those schools in Detroit.

Detroit schools, adds Maloney, have taken steps to hold down costs in their administration: 86 percent of them had no salaried business manager on staff in fiscal 2011, relying instead on consultants and contractors to perform those duties.

The earlier study by the national center “is a point in time indicator alone,” for judging administrative and instruction spending in charters, contends Maloney, who says that researchers need to consider that funding and spending “will vary within a state’s largest cities where many charters provide services.”