The recent White House Conference on Global Literacy hosted here by first lady Laura Bush coincided with the rollout of a new international assessment that holds the promise of providing a much more accurate picture of adult illiteracy in developing countries than ever before.

It is designed to help countries understand better the weaknesses in their primary and secondary school systems and nonformal education programs in order to reduce high illiteracy rates among all.

At the Sept. 18 conference at the New York Public Library, Mrs. Bush announced a donation of $1 million by the U.S. government to the Literacy Assessment and Monitoring Program, or LAMP, of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. (“President, First Lady Back Global Literacy to Fight ‘Hopelessness,’” Sept. 27, 2006.)

The United States is the first country to pledge money toward implementing the assessment that LAMP just finished crafting with $3.5 million of UNESCO funds, according to T. Scott Murray, the director of the Learning Outcomes Program of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, based in Montreal. He is hoping the White House support for literacy will attract other donors and boost the list of countries participating in the study, also called LAMP.

“The first thing you do to solve any problem is to understand it better,” said Mr. Murray, “This gives countries a tool to do that.”

The support for literacy by the first lady and President Bush, who both gave speeches at the conference, comes at a critical time, Mr. Murray said. “Countries are starting to wake up to the fact that the [LAMP] study exists,” he said, “but like any sort of advertisement, this is a very powerful endorsement, and it should help us secure higher levels of participation than we otherwise would have.”

The U.S. Department of State will distribute the $1 million donation. Last year, the U.S. Agency for International Development committed $250,000 to help Egypt administer the LAMP test.

Mr. Murray said UNESCO is now seeking donors to pay for all or part of the implementation of the assessment in 53 developing countries while at the same time trying to recruit those countries to take part. He estimates it will cost $250,000 to $500,000 for each country to carry out the test, depending on the sample size. El Salvador, Kenya, Mongolia, Morocco, Niger, and the Palestinian Autonomous Territories are participating in a pilot. Thirteen other developing countries, including Egypt, India, Jordan, Namibia, and Vietnam, have sent letters to UNESCO saying they intend to take part, he added.

Fine-Tuned Assessment

Experts in adult literacy say the new assessment holds the promise of telling much more about the level and nature of people’s literacy skills in developing countries than has been possible previously. The LAMP is an adaptation of an adult-literacy assessment that has been conducted only in industrialized countries.

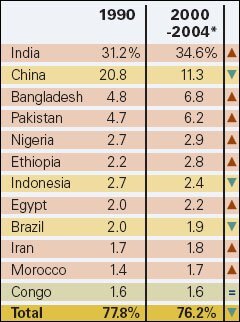

Three-quarters of the world’s illiterate adults live in a dozen countries; a third live in India.

* Data were collected between 2000 and 2004

SOURCE: UNESCO

UNESCO’s “Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2006” notes that 771 million adults in the world can’t read, and that 76 percent of them live in only 12 countries. Two-thirds of illiterate adults are women.

Up until now, most developing countries have counted anyone who goes to school as being literate, based on census surveys, literacy experts say. Yet, just because someone went to school doesn’t mean he or she learned to read, those experts point out. People who only went to school for a month or who were in a classroom with 90 children and had an unprepared teacher, for example, might be counted as literate.

“[The new test] will not only tell countries in a gross fashion, ‘Your school system isn’t producing enough people who can read,’ but ‘Here’s where your system is breaking down,’ ” said John Comings, the director of the National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy, located at Harvard University’s graduate school of education. The assessment could tell a developing country, for example, that its schools teach children to sound out words but do little to develop vocabulary, he said.

The assessment takes about 1½ hours, including a half-hour for questions about the test-taker’s background; it will be administered to adults who are at least 15 years old, according to Mr. Murray. It gauges both numeracy and a variety of reading skills, ranging from letter and word recognition to understanding the meaning of a text. It reports five different levels of reading proficiency in its results.

Base of Stability

In addition to citing the role of the White House conference in raising possible interest in the new assessment, literacy experts applauded the event for featuring panelists who described their work to improve literacy rates in their own countries. The projects combined literacy with other goals, such as teaching women about health or providing job opportunities for poor people.

Hasina Mojadidi, the instructional-development coordinator for a program in Afghanistan called Learning for Life, told how her country’s current government is trying to make up for six years in which girls and women were forbidden by the former Taliban regime to go to school. Her organization teaches women to read and about good hygiene practices at the same time. Ms. Mojadidi said many of the program’s learners have also been trained as midwives or traditional-birth attendants.

A facilitator for the Family Literacy Project in South Africa, Florence Molefe, said her group teaches mothers how to help their children learn to read, even if they can’t read themselves.

“They learn how to help prepare their children to read,” she said. “For example, mothers are encouraged to talk to their children when they go to the river to fetch water.” After the trip to the river, they can review what they have done, so the children can learn new vocabulary and sequencing, Ms. Molefe explained.

Janet Stahl, an international training consultant for SIL International, a Dallas-based Christian international organization, who has been working on literacy in Vanuatu, a nation in the South Pacific, said the conference highlighted projects that seemed to have succeeded in making literacy relevant.

She said she appreciated how some of the presenters, such as Gonzalo Fiorilo, the director of ALFALIT, a literacy organization in Bolivia, stressed the need to teach people to read in their native languages.

“We work in rural communities where multilingualism is a way of life,” Ms. Stahl said. “The people who tend to lose out on formal education are the ones who don’t acquire the official language very well, and would benefit from starting out in literacy in their own language and then transitioning.”

Ms. Stahl, and her husband, Jim Stahl, are working with the government of Vanuatu to set up teacher training and design materials to help 1st graders learn to read in their native languages. The country’s two official languages are French and English, and its national language is Bislama; its people speak 110 vernacular languages, she said.

As a follow-up to the White House conference, UNESCO plans to hold three regional conferences around the world in the next 18 months that will offer a chance for people there to discuss policies, research, and model programs that improve literacy, Peter P. Smith, UNESCO’s assistant director general for education, said in a telephone conversation last week from Paris. UNESCO was a partner in hosting the conference with the White House, along with the State Department, the U.S. Department of Education, and USAID.

“What we are trying to do is much more difficult than making a splash,” Mr. Smith said. “What we want to do is embed in political and policy dialogue globally, regionally, and nationally that education and literacy lie at the base of economic and social stability.”