Latinos have been the most visible group at the wave of immigrant-rights rallies across the country this spring. But youths of South Asian heritage in New York City want America to know that they and their families are the face of immigration, too.

Eighteen-year-old Sahmina Rahman, the U.S.-born daughter of immigrants from Bangladesh, is one of a small number of South Asian high school students here who have joined protests against federal proposals to crack down on illegal immigration.

Her family lives here legally, but Ms. Rahman says she knows that some South Asians are undocumented. She believes that they should be able to stay in the country, and that her city can’t function without immigrants, whether legal or not. Those beliefs prompted her and six other South Asian high school students to join an immigrant-rights rally in Manhattan last month.

“It’s our way to let everyone know we exist,” Ms. Rahman said in a recent interview. “I’d rather have more people from my country to make a difference—stand up for our rights.”

Of the estimated 11.1 million people in the United States illegally, about 8.7 million are from Latin America, according to the Washington-based Pew Hispanic Center. Nearly 500,000 are from South Asia; of them, about 400,000 come from India.

Simply given their smaller percentage, it’s not surprising that South Asians don’t have a higher profile in the immigration debates now roiling U.S. politics and society. But experts on South Asia also note other likely explanations.

“The community is very divided, both ethnically, religiously, and otherwise,” said Walter Andersen, the associate director of South Asia studies for John Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, located in Washington. “There are very few issues that unite them.”

Local group urges youths to be active in social issues

He added that many South Asians have been more active around the issue of H1B visas for skilled workers than federal policy dealing with illegal immigration.

Here in New York, Ms. Rahman had a little help before deciding to join in the upsurge of immigrant activism, which began in response to a bill passed by the U.S. House of Representatives in December with tough measures against illegal immigration.

Reaching Out

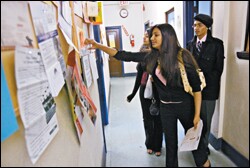

It was by being part of South Asian Youth Action, a nonprofit advocacy group operating out of a church basement in this diverse neighborhood of Queens, that she and her friends were urged to attend the April 10 rally.

Staff members of the group, which calls itself SAYA!, acknowledge that while many South Asians would be affected by new policies to stem the influx of illegal immigrants into the United States, they’ve been less vocal about the issue than Latinos have.

“In the Latino population, it’s being talked about,” said Tara Devineni, an Indian-American and the girls’ program coordinator for SAYA. “In the South Asian community, there’s a lot of silence about being undocumented. There’s a lot of fear about being deported.”

SAYA organizes education and leadership activities for students from the South Asian countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The organization also works with youths of Indian descent whose families emigrated from Guyana, a country in South America, and Trinidad, a Caribbean island northeast of Venezuela.

SAYA staff members and local educators say they don’t ask students if they are undocumented, but some youths share that information when they seek ways to go to college, even though it means they can’t get federal financial aid. New York is one of nine states, though, that let undocumented students pay in-state tuition rates.

One of the schools SAYA works with is Johns Adams High School, located near John F. Kennedy International Airport in Queens. The school’s principal, Grace Zwillenberg, says students who are undocumented come from a cross section of immigrant communities. About 90 percent of the school’s 3,500 students belong to minority groups, almost equally divided among African-Americans, Latinos, and South Asians, she says. Students of Indian descent whose families came from Guyana form the largest group of South Asians at the school.

So far, though, it’s John Adams’ Latino students, who have been the most active in pro-immigrant efforts, say teachers and students.

Graciela Gomez, a Spanish teacher, said only one of the 50 Latinos in her Spanish for Native Speakers classes came to school on May 1, the day that immigrant organizers called for immigrants to dramatize their contribution to the U.S. economy by staying home from work or school and not buying anything.

Breina Lampert, a teacher of English as a second language, also noted that while some Latino students in her classes were absent that day, her South Asian students came to school.

“The South Asian kids aren’t as aware as to what’s going on,” she said. “The focus on Mexico makes them feel they can pull away—‘That doesn’t speak to me.’ ”

South Asian students active in SAYA say that in their family culture, it is a really big deal to miss school, so youths in their community are likely to express their views in a different way.

Washington Watch

Immigrants from all backgrounds will likely get more opportunities to weigh in.

President Bush drew renewed attention to the issue in a nationally televised speech last week, in which he endorsed a plan that would include a path to citizenship for many people who are living in the United States illegally and meet certain criteria. He also called for 6,000 National Guard troops to be sent to the U.S.-Mexican border to help with efforts to curtail illegal immigration.

Meanwhile, members of the U.S. Senate continued work last week on crafting an immigration bill that would include a path to legalization for many undocumented workers as well as stepping up enforcement of border security.