Teachers in schools that participate in a program that overhauls their professional lives, in part by orienting their pay toward performance, are more likely to significantly raise student achievement than similar teachers in other public schools, the first broad evaluation of the Teacher Advancement Program has found.

Released last week, the report on the program launched five years ago by the Milken Family Foundation uses teacher-effectiveness data developed by researcher William Sanders, a pioneer in examining the “valued added” by individual teachers. The study itself was undertaken, however, by Lewis C. Solmon and colleagues at the National Institute for Excellence in Teaching, which operates TAP. Both the foundation and the institute are located in Santa Monica, Calif.

The program uses the value-added information to give varying awards to teachers and schools that have performed better than the state average over three years in raising student test scores.

Looking at Mr. Sanders’ calculations of learning gains for the students of 610 TAP teachers and more than 2,300 teachers in a comparison group on state tests taken in 2004 and 2005, the authors conclude not only that TAP teachers were more effective overall, but also that those schools do significantly better on average than other schools in producing learning gains.

The findings for TAP, which founders view as a comprehensive school-improvement program, come as many teacher-compensation models vie for the attention of policymakers. TAP did well last fall in a competition for $42 million in federal grant money earmarked for new forms of teacher pay. (“Teacher-Incentive Plans Geared to Bonuses for Individuals,” Nov. 15, 2006.)

Still, just over 130 schools in 14 states use the program. Other kinds of performance-pay plans—initiated by the Houston school board and the Florida legislature, for instance—affect many more schools.

Read the related story,

For teachers, the analysis showed that more of those in TAP schools had students scoring above the average amount of achievement growth estimated for the school year, based on Mr. Sanders’ data, and fewer had students scoring below the average amount. Twenty-five percent of TAP teachers had well above the average gain, compared with 14 percent of their non-TAP peers, for example. Thirty-eight percent of TAP teachers had smaller gains; for the comparison teachers, it was 26 percent.

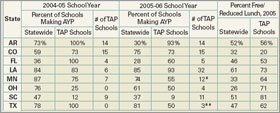

In some states, schools operating under the Teacher Advancement Program model were more likely to make adequate yearly progress than other public schools, and in other states, less so. TAP schools tend to enroll a greater percentage of students from poor families.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: National Institute for Excellence in Teaching

A comparison for schools showed that 40 percent of TAP schools and 32 percent of other schools in the study had gains above the average in test scores, while 26 percent of TAP schools and 18 percent of comparison schools racked up the larger increases. TAP schools were more likely to outperform their counterparts in reading than in math, the study found.

“What we’re seeing is that TAP teachers are getting more value added, in general, from their kids, and … TAP schools [are getting] more value-added gains from their kids than from similar schools,” said Mr. Solmon, the president of TAP’s parent organization and a former dean of the education school at the University of California, Los Angeles. “That’s what people want to know when making decisions about whether to go with TAP.”

Participant Satisfaction

The report’s authors also considered how well TAP schools met the goals set for students in the 2004-05 and 2005-06 school years under the No Child Left Behind Act, compared with other schools in the eight states with enough data to consider. In most cases, the authors said, TAP schools were at least as successful in making adequate yearly progress for students overall and for various subgroups defined in the federal law, even though they tended to have more students from poor families than the other schools.

Finally, the report looks at what teachers think of the program by way of annual surveys, especially compared with the attitudes of teachers generally. According to the researchers, most teachers in TAP schools endorsed the pillars of the program: opportunities for more responsibility and additional roles; ongoing, applied professional development; and evaluation and compensation tied to teaching accomplishment. The longer teachers were in the program, the stronger on average was their support, the authors found.

The report, “The Effectiveness of the Teacher Advancement Program,” is available from the National Institute for Excellence in Teaching.

Overall, according to the study, TAP teachers reported more satisfaction with professional development than their colleagues nationwide, as gauged by two national surveys. The program enhanced rather than undercut collaboration, the teachers said, despite the implementation of pay that varies by perceived accomplishment.

Still, TAP teachers were similar to teachers nationwide in disliking the idea of basing pay on student test scores. In fact, just 6 percent of the TAP teachers believed that standardized-test scores accurately represent the academic achievement of their students.

“I think we can get past about half the objections if we can [explain the value-added system] well,” said Mr. Solmon. “The fact that a kid has a bad day or you have low-achieving kids is not going to [negatively] affect you.”

‘The True Test’

Experts in teacher performance commended the worth of the study, while stopping short of calling it definitive.

“The evaluation of TAP schools shows clearly that teachers in the program are significantly better than the average teacher in regular public schools,” wrote Eric A. Hanushek, a prominent economist at Stanford University’s Hoover Institute, who has extensively studied the effects teachers in Texas have on student achievement.

“The finding is very notable given the importance of teachers for student achievement,” he added, in a review of the research he wrote for the authors and agreed to make public.

Matthew G. Springer, who directs the National Center on Performance at Vanderbilt University’s education school in Nashville, Tenn., said the study provides “preliminary evidence that TAP improves student outcomes in a number of comparisons.”

But, he cautioned, “as the authors themselves point out, the true test of the program” would involve a study independent of the program that randomly assigned half the participating schools to TAP and half to a control group.