Morning comes early for 17-year-old Monica Shaffer. She’s outside at 6:40, waiting high on Brown’s Mountain outside of Hacker Valley, West Virginia, with her younger brother, Raymond, when the feeder bus pulls off Replete Road. It’s the first leg of their 40-mile, nearly 90-minute trip to Webster County High School, located almost in the dead center of the state and the only secondary school in this sweeping, mountainous county.

The bus starts down the mountain, the road barely wide enough for it. A few younger kids who attend a preK-8 school in Hacker Valley, a settlement so small there’s not even a crossroads, share space with the high schoolers. The kids talk quietly, doze, or sit silently. No one reads or writes. Country music fills the interior. At the wheel is Clark Mollohan, who has been driving this route since Monica’s family moved to Webster County when she was in 5th grade. Mollohan has a cattle farm on a nearby river where Monica’s mother, Gloria, likes to fish for trout, and he knows their family well.

Monica’s family has “basically nothing,” Mollohan says, and the two teenagers “understand if they’re going to get anywhere, they’re going to do it on their own.” He’s encouraged Monica to continue her education, and on this spring morning, as school enters its final month, she’s already been accepted to Concord University, one of West Virginia’s best private colleges. Clad in a white T-shirt, jeans, and flip-flops, she has a solid case of senioritis and carries no books.

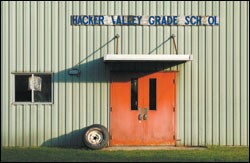

Ten miles on, the bus reaches the valley floor and pulls up next to the Hacker Valley School. But for Monica, another bus waits to take her and the other high schoolers the remaining 30 miles to the county’s high school, which replaced two smaller schools three decades ago.

Long bus rides are commonplace throughout West Virginia and in rural areas nationwide, where dwindling populations and tax bases have prompted districts to build larger schools to replace numerous smaller ones. Between 1990 and 2000, West Virginia’s statewide enrollment fell by 11 percent and 202 schools were closed, despite often vocal public opposition. Armed with the power of the purse, the state’s School Building Authority, which funds school construction, generally requires that facilities have minimum enrollments of between 200 and 800 students to receive state money for renovation, accelerating the push to consolidate aging facilities and build new ones.

“Unfortunately, West Virginia is pictured in national media and national myth as being woefully deficient,” says Craig Howley, an Ohio University education associate professor who studies rural issues. “Having big, shiny new schools is one way that politicians like to counter the image.”

While consolidation is an issue throughout rural America, West Virginia’s rugged topography has made it more emotional here as students spend up to four hours a day being bused to far-flung schools. The state leads the nation in the proportion of its education budget spent on transportation—nearly 7 percent, according to Challenge West Virginia, a grassroots group formed in 1997 to campaign against consolidation.

Rural communities have fought back by filing lawsuits, electing their allies to school boards, and defeating pro-consolidation bond issues. Here in Hacker Valley, community members have played a key role in helping the 75-student preK-8 school stay open—even undertaking much-needed repairs—to spare younger kids long bus rides like Monica’s daily journey.

After Monica and the other older kids switch to the second bus, it starts the long climb up Hodam Mountain and down into the hamlet of Diana, where another of the county’s four preK-8 schools is located. Then it’s on to Webster Springs, the county seat and home of the annual Woodchopping Festival. Timber is by far the county’s chief industry and one of its biggest employers, and the paltry seasonal wages men earn in the woods—some are lucky to earn $8,000 or $9,000 a year—help explain the area’s widespread destitution. With at least one-quarter of its people below the poverty line, Webster is the third-poorest county in a very poor state.

From Webster Springs, the road ascends a series of mountain switchbacks, treacherous in winter weather. Monica says the bus usually is so packed that students are jammed three to a seat, but they have legroom today because some are skipping. Finally, the high school appears, a one-story red-brick building sitting on a hillside. There’s a collection of homes not far away, but even closer to the school are cows grazing across the road.

Webster County High was built in 1974, after the county’s population fell nearly 30 percent in just a decade, to 9,800 people, where it remains today. Webster High has roughly 490 students, nearly two-thirds of whom receive free or reduced-price lunches. But it looks much like a suburban school, nothing about it suggesting poverty. While there are few frills, the library is attractive and well-appointed and the building clean. The achievements of the fine arts department and band are particular points of pride.

But as at other consolidated schools across West Virginia, Webster kids are often unable to join athletic teams or other extracurriculars because of difficulty getting home after games or activities on nights and weekends. Parent involvement is also often lacking. Monica, for example, has been shut out of nearly all extracurricular activities. She had to give up band midway through 9th grade because, after traveling to football games or music competitions held out of the county, she wouldn’t get back to Hacker Valley until anywhere from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m., and then her parents would have to drive down the mountain to fetch her. The school offers late buses leaving at 6 and 7:30 p.m., but they only go as far as Hacker Valley School, and the Shaffers, both of whom are medically disabled and live on a fixed income, can’t afford the 20-mile round trip to pick up Monica in their 14-year-old gas-guzzling truck. Getting to the high school for parent functions would cost $20, she says, so they almost never do.

While Monica holds the second-highest position in her school’s JROTC unit, battalion executive officer, she hasn’t been able to participate in the color guard or drill team. It wasn’t until Monica became a senior that she did anything else extracurricular, joining an after-school program that gave her time to study and to learn photography. An evening job at a fast-food eatery helps pay for the gas her parents use to meet the late bus.

Webster works hard to accommodate its far-flung students. Many extracurricular activities meet during lunch. Theater, choir, dance, and band rehearsals are often held in class. Teenagers do not split into cliques based on their hometowns (a Hacker Valley girl was elected prom queen by peers from across the county this year), largely because nearly everyone lives so far away from the school that riding the bus holds no stigma. The dropout rate has declined steadily in recent years and is below the state average, thanks in partto an alternative center for adolescents who would otherwise leave.

Principal Paula Varney, who’s been at the school since it opened, credits the school’s size and the stability of its teaching force. “Everybody knows everybody by name,” agrees social studies and law teacher Cara Phillips. Teachers help sew costumes for the drama department or assist the track coach for no extra pay. When teams stop to eat on trips to games, coaches shell out for players who have no money, and kids frequently invite athletes, band members, and cheerleaders who return late from away games to spend the night at their homes. And the school’s adviser system keeps the same 12 to 15 adolescents meeting weekly with the same counselor for four years.

There’s a sense of community despite the long distances students travel. In August 2004, two football players driving home from practice were killed and another badly injured. Within hours, coaches, students, teachers, parents, and counselors started gathering at the school, and plans were made for a candlelight service a few days later. “It was probably 1, 2 in the morning before everyone left,” says Varney.

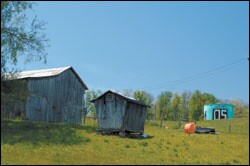

There’s a similar feeling of community at Hacker Valley’s school. But the only store left in town is a grocery that makes sandwiches and sells gas. There’s also a small diner, two churches, a senior citizen center, and a volunteer fire department spread out for a mile along the road. A few regulars sit around most days and talk for hours at Holly River Grocery. Otherwise, it’s very quiet.

At one end of the village is a large sawmill. In Hacker Valley’s heyday in the 1920s, there was also a company store and boarding house for men who worked at the mill, according to local historian Stanley “Judd” Anderson. A nearby enclave was nicknamed Little Italy for its ethnic makeup. Mail was delivered on horseback to surrounding communities, and people rode in the caboose of a freight train across the mountains to another town.

That was the era of the one-room schoolhouse, but because of its size, Hacker Valley had a two-room school. It closed in the 1960s, when the school’s three present-day buildings were erected for the area’s preK-8 students. At that time, Anderson says, the school bus only followed the main road, and students who, like Monica, lived miles away in the mountains would board with a family closer to the road.

Today, Hacker Valley School is so small that faculty teach two and three grades in the same room, the principal and special education teacher spend half their time at another preK-8 school, the guidance counselor, nurse, and speech and gifted teachers come just once a week, and Mollohan keeps staff apprised of family problems along his bus route. “You wear a lot of hats,” says Kennetha Howes, who teaches 3rd, 4th, and 5th grades. So do community members, including a core group of volunteers who often spend the entire day at the school. Monica, who attended the school from 5th through 8th grades, liked the one-on-one attention. “A little school like HV, they’re really there for you,” she says.

Howes, a casually dressed, good-natured woman, gives her students a considerable measure of freedom. This morning, she took her kids outside to plant flowers along the school’s sidewalks, then turned them loose on the school grounds for more than 30 minutes. Special ed teacher Renee Anderson says that because of the school’s size and laid-back atmosphere, there’s not much bullying, even among students who’ve been kicked out of larger schools elsewhere. “These kids tend to feel they’re part of things,” she says.

Hacker Valley’s academic credentials are sterling—this year, state education officials granted it exemplary accreditation status, the only school in the county to be so honored. Anita Pugh, who teaches math to most classes, attributes its success to knowing individual students’ strengths and weaknesses. Were Hacker Valley to close, she says, “they would not have that somewhere else.”

In the early 1990s, Webster County’s cash-strapped school board, citing the school’s small enrollment, sought to do just that. The community rallied behind a local group called Put Children Firstto fend off the immediate threat, then later lobbied state lawmakers to help cover the school’s operating expenses. But the aging, poorly insulated buildings, originally intended to be temporary, have been falling into disrepair. Community members installed a new roof on the classroom trailer and, in 2001, began a drive to build a new school themselves. Led by Put Children First, residents commissioned a local architect and gathered pledges for $54,000 in cash and 3,200 hours of manpower, according to Cindy Miller, the county’s Challenge WV rep, who also helped organize the local effort. Still $100,000 short, the build-it-yourself campaign continues.

Miller, whose family has lived in a nearby area known as Panther Lick for six generations, understands the strong emotions that tie the community to its school. The daughter of a logger, Miller became a teacher, as did her husband, Kevin. But local jobs are scarce, and for years he has arisen before dawn and driven nearly two hours to a government job in Clarksburg. “One of the main reasons we stay,” Cindy Miller says, “is so our children can attend a small community school.”

At 3:40, the bus back to Hacker Valley leaves Webster High School for the day. Talking loudly and joking, the teenagers are far more lively than they were this morning. Not far from Webster Springs, the bus gets stuck behind a slow-moving logging truck, but once Arden Wilkins, the driver, skirts the truck and clears town, he shows why he’s known for making time.

It’s around 5 when the feeder bus lets off Monica and Raymond at their home. They live in an unpainted, gunmetal gray frame house with walls that don’t fully connect. There are few windows. Family photos and American Indianart adorn the main room, but there is no wallpaper, no running water, and little in the kitchen but a cook’s table. Once home, “you really don’t have time to do anything except homework,” Monica says.

These long days have begun to influence state politics. Democrat Joe Manchin, who, like his opponent, ran in support of small schools, was elected governor of West Virginia in 2004. He supported a bill to set time limits on bus rides, largely written by Challenge WV, which later died in committee. Linda Martin, the group’s director, says Manchin has since backed away from supporting the bill. Martin calls the situation urgent because more than 150 schools, many of them primaries, are still in danger of closing. “We’re going to have thousands of 5-year-olds riding school buses two hours one way,” she says.

In the meantime, Monica is preparing for life after graduation. Proud of her time in JROTC, she was once determined to join the military after high school, but she also applied to Concord, hoping financial aid would somehow make it possible. Now that she’s college-bound, she’s been able to line up two grants and plans to take out loans and work afternoons in Concord’s admissions office.

She’s also the family wage-earner; when her father developed cancer, she helped pay for his treatment. Living in the mountains and with animals means a lot to Monica. She is always bringing home stray dogs, and the Shaffers now have cats, ferrets, hamsters, and sugar gliders, a marsupial resembling a flying squirrel. She grew up hunting and fishing with her dad, Ray, who keeps her car running.

“We have hardship,” Ray says, “but we have love, and love overcomes a lot of hardship.”

As summer approaches, Monica plans to spend the season working at two fast-food restaurants to help make ends meet. One of her teachers, Jane Gamble, recalls that Monica recently complained to her about the job. “She said, ‘I don’t know if I’m going to make it till August. ... It’s the pits.’ ” But when Gamble asked what work had taught her, Monica replied that “come September, I’m going to be in college, and I’m going to get a degree, so I’m not going to be working at Kentucky Fried Chicken for the rest of my life.”