American children spend about six hours a day in their schools, much of that time in buildings that are decades old, deteriorating, and in need of significant repairs.

Those conditions are a direct result of the nation’s underinvestment in public school facilities—a lack of support that falls short by $46 billion annually, according to a new report on the state of America’s K-12 infrastructure.

“It is totally unacceptable that there are millions of students across the country who are learning in dilapidated, obsolete, and unhealthy facilities that pose obstacles to their learning and overall well-being,” said Rick Fedrizzi, the CEO and founding chairman of the U.S. Green Business Council, whose group co-authored the report with the 21st Century School Fund, and the National Council on School Facilities, groups that push for modernizing school buildings.

“U.S. public school infrastructure is funded through a system that is inequitably affecting our nation’s students, and this has to change,” Fedrizzi said.

While the physical conditions of schools—the average age of a U.S. school is 44 years old—are known to have some effects on how students do in the classroom, the topic has not garnered as much attention as other factors that weigh heavily on student learning.

But concerns over lead-tainted drinking water in schools and communities in recent months—most notably in Flint, Mich., and Newark, N.J.—are bringing renewed attention to the age and conditions of buildings.

In Detroit, teachers have been staging periodic sickouts this year, in part to draw attention to that city’s dilapidated and unsanitary building conditions. And air quality also is a major concern in many school districts.

The last in-depth, federal examination of the condition of K-12 facilities was released more than 20 years ago, in 1995, by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

At that time, the GAO said that public schools needed to spend an estimated $112 billion to repair or upgrade their facilities to “good condition,” and about 14 million students were attending schools that needed “extensive repairs.”

And with widely varying funding models and levels of need among states and local jurisdictions, it remains challenging to collect comprehensive and accurate information on how much is being spent on K-12 facilities, the new report finds.

Funding Varies State to State

The authors drew from two decades of publicly available state and federal data on public facilities spending, as well as data from the U.S. Census, the National Center for Education Statistics, and districts. They noted that capital construction investment data in 18 states might have been underreported.

At the same time that school buildings are aging and resources to maintain and update them are running short in many districts, enrollment growth in some states is putting new pressures on K-12 officials to build new schools.

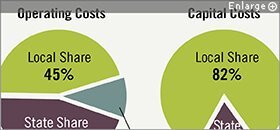

Source: 2016 State of Our Schools: America’s K-12 Facilities

To keep buildings in good working order and upgrade existing building stock, districts should be collectively spending at least $145 billion each year, the authors said.

From 1994 to 2013, only three states—Texas, Florida, and Georgia—met or exceeded the minimum industry standard for capital construction investment, the report said. Vermont, Montana, and Rhode Island were among the states that, on average, spent the least on capital construction during those years.

Districts spent $925 billion in 2014 dollars on maintenance and operations during the years 1994 to 2013—an average of about $46 billion annually.

School districts also had heavy debt loads from capital spending, with about $409 billion in long-term debt at the end of 2013 that was largely attributable to capital facilities projects. They reported paying $17 billion that year in interest on those projects, or about $8,465, on average, per school child, according to the report.

Infrastructure spending also varied from state to state, and districts reported receiving only small amounts of directed federal aid to help with construction.

Hawaii, for example, which has a single school district for all of its schools, shoulders all capital costs associated with school facilities. Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Wyoming contributed more than half of district’s capital investment dollars. A dozen states, including Indiana and Michigan, have no direct state support for capital facilities expenditures, according to the report.

Reliance on Local Support

That means districts often rely on local taxpayers to approve pricey bonds to pay for needed upgrades.

In Fort Wayne, Ind., a district of roughly 30,000 students, school officials know this well. The district’s buildings, many of them built cheaply in the 1950s, ‘60s and early ‘70s to accommodate Baby Boomers, started to show their age in the early 2000s.

Some had no air conditioners, used dull, outdated lighting, and had windows that were not energy efficient, said Krista Stockman, the district’s spokeswoman.

In 2007, the district asked voters to approve a $500 million bond issue over 20 years to address those problems, pay for adding space for nursing offices, and for prekindergarten and kindergarten classrooms, and to make security and technology upgrades. Voters said no.

“It was hard for people to see that this was a 20-year span,” Stockman said. “They thought there were things [included] that we didn’t really need.”

After that rejection, district officials spent the next five years working to convince voters that the spending was necessary, and in 2012, a smaller, $119 million bond measure passed. The money was used for renovations on 36 buildings with significant problems.

“Classrooms are brighter,” Wendy Robinson, Fort Wayne’s superintendent for 13 years, said in an email. “Air quality is better. Students are able to focus on their work and not on wildly fluctuating temperatures.”

But because Indiana does not have a dedicated funding source to help districts with such projects, the Fort Wayne district is going back to voters in May to approve a $130 million bond to pay for more upgrades.

Robinson said that while reliance on local taxpayers appeared sound in theory to maintain local input over K-12 spending, it has created a system of haves and have-nots.

“Wealthier areas with higher property values and residents who have more ability to afford additional taxes will be better able to support capital needs, including technology updates,” she said.

“Areas with more poverty, meanwhile, will collect less in property taxes, resulting in fewer building and technology improvements,” Robinson continued. “This has created a situation where over time, school districts have fallen behind in routine maintenance, which then requires spending more on an emergency basis, only exacerbating the funding problem.”

A Bigger Pie?

The new report bears out some of Robinson’s concerns.

It cited previous studies that indicated that schools in wealthier ZIP codes tended to make more capital investments in schools, while those in less affluent areas tended to spend a bigger portion of their operational funds—the same bucket of money used for teacher salaries and instructional materials—for repairs and maintenance.

The groups behind the report called for more accurate and accessible data on infrastructure spending to help citizens and local officials; strategic planning that encompasses both maintenance and operations and capital outlays; leveraging public and private partnerships; and finding new public funding to support school facilities.

Even as many districts can’t keep spending on pace to maintain buildings, they also are facing growing pressures to add space for predicted enrollment increases, which the report estimates would cost $10 billion annually through 2024.

More money is needed, but planning is also important, said Mary Filardo, the executive director of the Washington-based 21 Century School Fund.

“We do need new public dollars; there aren’t enough public dollars out there,” she said, adding that it was not just a matter of shifting things around.

“The pie itself needs to be bigger.”