Cecil J. Picard walks confidently and purposefully to his seat, using a cane to support his weakening right leg. The widow’s peak and his graying hair are signs that he’s lived 68 years, and the cane serves notice that he isn’t as strong as he used to be.

Mr. Picard is here today for one in a series of public meetings on solving the biggest problem he’s taken on in 40-plus years as an educator and politician: rebuilding the storm-ravaged New Orleans public schools.

At the same time, he’s fighting a personal battle that he almost certainly won’t win: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

In his career, he’s led two high schools through desegregation. He’s pushed to improve teacher quality and hold schools accountable as a state legislator. He’s built Louisiana’s nationally recognized system of testing and accountability as the state schools chief.

Now, he must open 35 schools here by August. That won’t be easy in a city where rubble piles are ubiquitous and utility service is still spotty almost 10 months after Hurricane Katrina struck, and where the federal bureaucracy has yet to deliver the money to finance school repairs.

Yet, Mr. Picard says the state will have the schools ready for students this summer. Within five years, he hopes to transform the city’s schools—which were nearly bankrupt, academically and financially, even before Katrina’s floodwaters overwhelmed the city last August—and make them the best urban schools in the nation.

Today, he’s attending a meeting of the board he formed to advise him on the process of rebuilding education in New Orleans. Paul G. Pastorek, the chairman of the board, says he told the state superintendent to skip the meeting—one of many efforts by the chief’s admirers to help him conserve his energy.

But Mr. Picard came anyway, traveling 80 miles from the state capital, Baton Rouge, to hear what the advisory panelists and members of the public have to say about the plan.

“For the first time, in the past couple of weeks, things are starting to come together,” he tells the group. “It’s not too early to let the people know” what’s happening, he says.

He also reminds them that the emergency legislation that gave the state control over most of the district’s schools didn’t create such an advisory board. Mr. Picard did so as a way to get input from city leaders and statewide groups. In the end, the state board of education—working on advice from Mr. Picard and his handpicked acting superintendent in the city—will decide on how to run the schools that had been New Orleans’ worst before the flood.

In the 10 years Mr. Picard has been Louisiana’s superintendent, the state’s schools have made dramatic progress. Louisiana regularly receives some of the highest grades in Quality Counts, Education Week’s annual report on state education policies and performance. The state is nationally recognized for setting challenging academic standards and building a testing and accountability system to measure whether students are meeting them.

Cecil J. Picard in his 1955 high school graduation photo. His father was a school principal in Superintendent Picard’s hometown of Maurice, La., where the Picards lived in a house provided by the school board.

Photo courtesy of Cecil Picard.

That work has paid off in student achievement, as measured by the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Louisiana was one of seven states in which low-income students’ reading scores rose at faster rates than those of other students on NAEP reading tests between 1996 and 2005. On the national math exam, Louisiana was one of six states whose percentage of low-income students scoring at “basic” or higher grew by 20 or more points between 1998 and 2005, according to an analysis by the Washington-based Council of Chief State School Officers.

“That state has probably made more progress than any other state, especially any of the states that started as low as they did,” said Kati Haycock, the executive director of the Education Trust, a Washington-based group that promotes school improvement for disadvantaged students.

“Cecil’s not always leading the charge, but he’s certainly been at or near the front,” she said.

Mr. Picard and his team now face a tougher challenge. In New Orleans, where the state is in charge of most of the city’s public schools, they are starting over with an urban school system that had long been on the ropes and full of substandard school facilities—and now walloped by one of the worst natural disasters in the nation’s history.

No one has written a blueprint for doing that.

The draft plan circulated at the May 25 meeting says the state wants to build “a fundamentally different school system that will set higher expectations, and deliver higher-quality support to schools and students than ever before, where everyone in this new system will have an important role and responsibility to support student learning.”

It also explains how the state will work with the patchwork of schools throughout the city, with some run by the city’s school board and others operating under charters granted either by the city or the state.

By this summer, the state projects, 34,000 students will be attending public schools in the city—little more than half the pre-Katrina enrollment.

Even Mr. Picard acknowledges that the document is just a starting point. “This is a golden opportunity to build a first-class system from the ground up,” he says later in an interview.

Mr. Picard (pronounced “PEA-card”) has faced difficult situations at other points in his career.

In 1966, he became the principal of Maurice High School, succeeding his father who had died shortly before the school year began. At the age of 29, he oversaw the integration of black and white students in the rural community of Maurice, just outside Lafayette.

That job was relatively easy, he says in the interview, because he was working in the community where he grew up, the son of the principal of the town’s school for whites. “We all grew up together,” he says of black and white children. “We all—not socialized—but had good acquaintances.”

When he moved to Abbeville High School—in a bigger town 10 miles away, but still in Vermilion Parish—the white and black communities didn’t coexist as well as in Maurice.

In 1969, his first year there, one of the school’s 250 African-Americans was elected to the homecoming court. But the next fall, none won that honor. After a riot broke out in the school’s parking lot in protest, the school board pushed Mr. Picard to add a black student to the court. He said he’d rather resign. It would ruin his credibility with the school’s 800 white students, he said.

He restored order by expelling 14 students who had either assaulted a teacher or destroyed property during the riot. He also installed a strict code of conduct and clamped down on student loitering in the halls and smoking on school grounds. “All basic things,” he says. (More than 30 years later, propriety still matters. The Louisiana education agency under Mr. Picard has one of the strictest dress codes in the state government. Men must wear ties and dress shoes, for example, and women can’t wear Capri-style pants or flip-flops.)

The next year, though, he convinced Abbeville’s white community that African-Americans should be on the homecoming court, even if it meant leaving off a white student who had more votes. “They saw it as the only way we could save the school,” he says now, confident that he did the right thing.

Desegregating a school in the Deep South was probably the toughest job an educator could face in the 20th century. Today, in New Orleans, Mr. Picard may have the toughest task facing any educator in the country. Is it more difficult than desegregating a high school in 1969?

“Yes,” he says in the interview, “because the amount of corruption and the amount of distrust and the amount of tragedy that this city has experienced makes the job greater.”

Even before the storm, the legislature had given Mr. Picard the authority to take over the district’s finances because audits had found fraudulent paychecks and other graft in its records.

But Mr. Picard says he’s using many of the same tactics to rebuild the New Orleans schools as when he was a local superintendent and since becoming the state chief in 1996. He took the job after then-Gov. Mike Foster, a former state Senate colleague, nominated him and the state board formally appointed him.

For example, by forming an advisory board that includes New Orleans officials—including two members of the Orleans Parish school board, a mayoral adviser, and a charter school principal—he’s given city leaders a voice in the process.

He also told the state team drafting the plan to hold three public hearings on the plan in the week before the May 25 advisory board meeting.

Still, he has critics in the city, many of whom take issue with his move to dismiss the district’s employees and make them reapply for their jobs.

“To operate these schools from Baton Rouge doesn’t make sense,” said Willie Zanders, a lawyer who is suing the state to end the school takeover.

But Mr. Picard says such critics have gained little traction because the state has given city leaders a voice in the state’s plans.

“They don’t have anything to hold on to,” he says of opponents. “We have disseminated the information, and we are saying there will be a school for everybody who comes back in August. The only thing they can say is, ‘The state is taking over our schools.’ That doesn’t hold any water with the good, solid families who have been calling me for months saying, ‘Please, take us over.’ ”

His cellphone, sounding like an obnoxious teenager, announces another call: “Hey, your phone is ringing!” He grabs the phone as he sits in the passenger seat of his black Chevrolet Suburban. While his assistant drives him back to Baton Rouge, he’s fielding and making calls, occasionally sipping water.

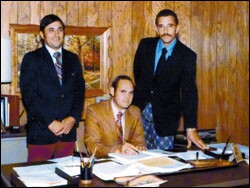

After a three-year stint as the principal in his hometown school, Mr. Picard, seated, moved up the road to be the principal of Abbeville High School, where he dealt with racial tension as the school was desegregated.

Photo courtesy of Cecil Picard.

On the phone, Mr. Picard is short and to the point. Will the state Senate be in session tomorrow, he asks a switchboard operator at the Louisiana Capitol. Find out whether a Senate committee adopted any amendments to a bill it approved this morning, he tells a staff member.

It’s nearing 3 p.m.—the time of day that Mr. Picard says fatigue induced by ALS starts setting in.

The A in ALS stands for amyotrophic. In Greek, a means no, myo means muscle, and trophic means nourishment. No muscle nourishment. That’s what happens when ALS attacks, according to the ALS Association’s Web site.

The brain neurons of people with ALS lose the ability to communicate with muscles through the spinal cord, and their muscles slowly waste away. Doctors haven’t found a way to reverse the steady and sometimes rapid slide. Few people live longer than five years after being diagnosed.

Mr. Picard sought treatment in early 2005 for an unexplained weakness in his right leg and hip. Doctors told him he had ALS. In May of last year, he announced his disease to the public and said he would stay on the job.

He was 67—an age when most people are retired and enjoying family. Mr. Picard and his wife, Gaylen, have two children and four grandchildren.

“There is no treatment, there is no cure for ALS,” he says from the front seat.

A pause.

“My therapy is going to work every day.”

His right leg is getting weaker, but he doesn’t feel any pain in it. His left leg hasn’t lost any of its strength. The only other symptom he notices is a slight hoarseness in his voice—something someone meeting him for the first time wouldn’t notice.

Because the disease doesn’t affect his acumen, he adds, he’s able to do all the strategic thinking and political maneuvering that’s required in his post.

Those who work with him say he hasn’t lost any of his ability to look at problems and quickly decide what needs to be done to fix them. With those skills intact, he says he wants to stay in his job until his contract expires on Dec. 31, 2007—the day before his 70th birthday.

He’ll be at the end of a long career during which he changed the face of schools in his home parish and gained national recognition for dramatically improving schools throughout his state.

By the end of next year, he’ll possibly get credit for turning around one of the worst school systems in the country.

He’ll be ready to retire.