Sunday’s New York Times featured an article on the growing practice of visualization among Olympic athletes. Medalists like Mikaela Shiffrin, the 18-year old American who is arguably the best skier in the world, imagine every vivid detail in advance--tight turns on an upcoming luge course, the moment of impact as their skis strike snow after an aerial jump.

The article noted that “athletes who were adept at imaginary play as children--'imaginary friends, make believe'--were better at imagery.”

Can visualization help our students learn new skills and concepts?

Consider the three examples below. I’d love to hear more from any of you who have used visualization in your teaching.

1. Reading

I teach 2nd grade, generally the year when students move from picture books to chapter books. In picture books, the illustrator has already done much of the work involved in making mental images. The reader sees the characters, setting, and action on every page.

Chapter books are different. For the first time, kids need to imagine what Esperanza’s face looks like when her family loses their vineyard. They conjure up the barn in Charlotte’s Web with its “wonderful sweet breath of patient cows.” It’s up to them to imagine the battle between Narnians and the White Witch’s minions. There are a handful of illustrations --the cover, sometimes a few drawings for each chapter--but the progression toward reading as an interaction with print alone has begun.

Comprehension rests in large part on a young reader’s ability to imagine scenes and images. That process by which inked squiggles and dots become a story is mystical, in a way.

Adult readers who have found themselves in the grip of a story long after midnight on a work night can relate. On the surface, we’re just converting visual symbols into meaning. But the process is more dramatic than that. We see a black sky streaked by lightning, hear Voldemort’s unearthly laughter, feel our heart clench as Nazi guards lead Sophie’s daughter away.

When I’m teaching kids to transition from picture books to chapter books during Read Aloud, I’ll often read a passage a couple of times, then have them draw the picture they conjure in their heads. Kids flip this process during Writers’ Workshop; in mini-lessons on descriptive writing, we talk about a writer’s goal to “make a movie” in the reader’s mind.

Other senses come into play, too. When I read Owl Moon and The Polar Express to my 2nd graders, we turn off the lights and open the windows to the cold breeze to set the solemn, midnight mood of those books. Reading is often most engaging when it becomes a sensory act, and our minds can conjure sound, smell, taste, and touch along with visual images.

2. Math

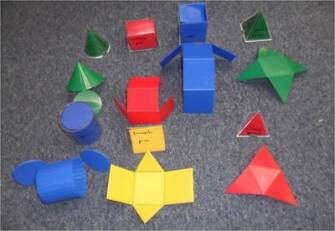

One of my favorite geometry lessons involves manipulatives of 3-D solids--pyramids, cylinders, prisms--that unfold into their 2-D faces, or nets. The kids first try to visualize what the 3-D solid will like once it’s unfolded. They draw their prediction, then unfold the manipulative to see how close they came.

My students use visualization in almost every math lesson, whether they’re imagining the objects and actions described in a word problem, mentally decomposing a large number by visualizing place value blocks, or picturing the quantities for a measurement question involving volume. Number sense often begins with tactile experiences, and visualization is a logical next step once students no longer need manipulatives for a given concept.

3. Imaginary Field Trips

Most kids learn better when we engage their senses, whether they’re tearing apart an old log to see which insects scurry out or making motions for new vocabulary through Total Physical Response. Linking senses to imagination can be powerful, as most Olympic athletes can attest.

Having kids close their eyes and imagine sensations can be a central part of perspective taking. With fiction, we might ask our students to experience the physical trembling that overtakes the child in Roald Dahl’s The Witches when he realizes he’s trapped in a roomful of bald, child-sniffing witches. With Social Studies lessons and historical fiction, we might have them imagine the salt spray off the ocean as they arrive at Ellis Island at the turn of the century.

As part of an international unit at our school, each grade level set up a display in the hallway to represent a different country: Mexico, Egypt, the Marshall Islands. The kids had passports to stamp as they entered each country, and when we lined up to visit the nations scattered across the school, I asked the 2nd graders to pretend they were boarding an airplane.

Many of my students had never been on a plane, but they happily suspended disbelief. They found their seats, reclined to a comfortable angle, and settled in to enjoy the journey. I asked them to sip the sodas from their imaginary plastic cups, and they did; to look down at the mountains and rivers 30,000 feet below, and they did. For some reason, though, when I asked them to open their little foil bags of peanuts, Salvador’s skinny arm shot into the air.

“Mr. Minkel! We don’t have any peanuts.” He was deadly serious.

I just looked at him in disbelief and said, “Salvador, we don’t have an airplane, either--this is all make believe.”

Part of what I love about teaching seven- and eight-year olds is that they’re simultaneously capable of swooping flights of imagination and stubborn immersion in the tangible world of what can be seen, smelled, tasted, and touched. Visualization is a way to link those two traits in the service of anything we want to teach.

By bringing an imagined sensory experience into Science, Read Aloud, Writers’ Workshop, Social Studies, Math, or any other subject, kids can experience a simulation that might stick with them long after a teacher lecture has evaporated.

Emily Cook, the American Olympic aerialist, said, “You have to smell it. You have to hear it. You have to feel it, everything.” Canadian bobsledder Lyndon Rush shared a thought worth imparting to any child: “It’s amazing how much you can do in your mind.”

Note: The unfolding geometric shapes in the photo I took are available from Learning Resources.