Amid the recent wave of large-scale teacher protests over pay, states should be supporting districts to strategically rethink teacher compensation, one report says.

A new policy brief by the National Council on Teacher Quality, a Washington-based think tank, examines teacher pay for each state and the District of Columbia—and concludes that states should be doing more to make sure teachers are “meaningfully compensated” for exemplary teaching.

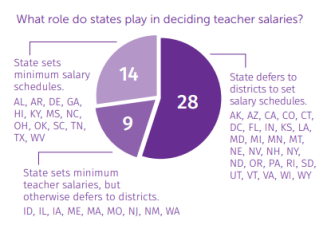

Typically, decisions about teacher pay are left up to individual school districts. Most districts have a “step and lane” salary schedule—teachers earn a “step” increase in pay for each additional year of experience, and can earn a “lane” increase by having more education. In most states, these salary schedules are determined through collective bargaining, which is a process in which local teachers’ unions negotiate salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other factors with the school district.

See also: Teacher Pay: How Salaries, Pensions, and Benefits Work in Schools

Only a handful of states have a statewide salary schedule that establishes a minimum salary for teachers (though districts can go beyond what the state requires).

But NCTQ wants states to go beyond counting years of experience and degrees earned, and consider rewarding teachers for other factors. The group counts just nine states that require districts to consider performance in their teacher compensation—and only three states that require districts to consider new teachers’ relevant, non-teaching work experience when determining starting salaries. Thirty-five states explicitly support additional compensation or incentives for teachers who work in high-needs schools and/or subjects—a practice supported by NCTQ.

While NCTQ supports differentiated pay structures and linking salary increases to teacher evaluation, those policies are controversial and have been hotly debated for over a decade. Past research has been mixed on how performance-pay initiatives affect student achievement, although a recent study found that in schools that offered pay-for-performance bonuses, students got the equivalent of four weeks of additional learning.

The report lists a few states that NCTQ considers to have promising practices regarding compensation. School districts in Louisiana establish salary schedules based on teacher effectiveness; prior experience; and demand (certification area, the particular school, geographic area, and/or the subject-area need). Districts can provide stipends to teachers in shortage-area subjects and low-performing or high-poverty schools, and can compensate new teachers for their prior relevant, non-teaching experience—so an engineer who wants to become a high school science teacher, for example, will get credit on the salary schedule for his prior work as an engineer. Louisiana also says that any teacher who was rated ineffective may not receive a salary increase the following year.

Meanwhile, Utah requires districts to base their compensation systems on annual teacher evaluations. Teachers who score well on their evaluations receive raises and teachers who are rated ineffective do not receive any salary advancement. Effective teachers can receive an additional stipend to teach in high-needs schools and subjects.

NCTQ also points to North Carolina as a state that’s doing something right: The state gives financial rewards to highly qualified teaching graduates who teach in a shortage-area subject or in low-performing schools during the first few years of their careers. North Carolina also moves teachers with relevant, non-teaching experience up one year on the salary schedule for every year of experience after earning a bachelor’s degree.

However, despite those policies, North Carolina teachers are still engaging in a widespread protest over pay and school funding. Teachers there are requesting leave in mass for May 16 to protest at the state capitol, forcing districts across the state to cancel classes. North Carolina is the latest state to see such large-scale teacher activism: Teachers in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona all went on strike over low pay, and in each case, they ended the work stoppage with a salary increase. Teachers in Colorado have also closed districts across the state as they protested at the capitol for higher wages and more school funding.

It’s important to note that in all of these walkouts and protests, teacher evaluation and other performance-related policies have been conspicuously left out of the narrative. As my colleague Stephen Sawchuk reported, lawmakers are not trying to attach any performance-related strings to the salary increases they have awarded striking teachers.

“Even supporters [of teacher-performance policies] want to keep those efforts under the radar screen, and that’s why you’re not seeing people connecting the issue of teacher compensation and performance in this outbreak of labor unrest,” Martin West, an associate professor of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, told Sawchuk for the article (which was published before NCTQ’s report came out).

See also: The Teachers Are Winning. What Does It Mean for the Profession?

NCTQ recommends that states should set parameters for districts to develop compensation systems, including taking into account teacher effectiveness, the school and subject area the teacher is working in, and relevant, non-teaching experience. The group also encourages states to work with districts to identify funding for these practices.

“Even in a resource-constrained environment, every state has the opportunity to be strategic about how compensation resources are allocated,” the report concludes. Readers can examine the compensation policies in each state here.

Image via Getty, chart courtesy of the National Council on Teacher Quality