(This is the third post in a four-part series. You can see Part One here and Part Two here.)

The new “question-of-the-week” is:

What is the biggest mistake teachers make in reading instruction, and what should they do instead?

Contributors to Part One were Diana Laufenberg, Pernille Ripp, Valentina Gonzalez, Jeff Wilhelm, Barbara A. Marinak, and Linda B. Gambrell. You can listen to a 10-minute conversation I had with Diana, Pernille, Valentina and Jeff on my BAM! Radio Show. You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

Part Two‘s guests were Regie Routman, Cindi Rigsbee, Shaeley Santiago, Wiley Blevins, and Dr. Rebecca Alber.

Today’s guest responses are written by Gravity Goldberg, Renee Houser, Tan Huynh, Samantha Cleaver, Jeffrey D. Wilhelm (with his second contribution to this series), Emily Geltz, and Sarah Shanks.

Response From Gravity Goldberg & Renee Houser

Gravity Goldberg and Renee Houser are literacy consultants and authors of the books What Do I Teach Readers Tomorrow? Fiction and Nonfiction (Corwin Literacy, 2017). They blog at gravityandrenee.com and can be reached at @drgravityg and @ReneeDHouser:

Mindset of Mistrust: As we work with teachers around the country, we all want what is best for readers and we all want to get it “right.” The problem is that educational policies and beliefs have created a mindset of mistrust when it comes to reading teachers’ ability to decide what is “right.” This has led to billions of dollars and too-many-to-count hours of program specific training, that forces teachers to outsource their instructional decision-making. Outsourcing decisions tends to look like this: following a prescribed teacher’s guide, using a basal reading program exactly as it was scripted, and handing teachers’ modules to follow to the word. What outsourcing causes us to miss is that getting it “right” is not the same for every school, classroom, or child. Therefore, the only way to do what is best for student readers is to base instructional decisions on what we as teachers have uncovered about our particular students.

The Cause: One cause for this problem is the assumption that there is one right answer when it comes to deciding on what to teach student readers each day. Reading is a deeply personal and idiosyncratic process and, therefore, our teaching must be responsive to who are students are. Another cause is the focus on alignment between classrooms and consistency across a district, which can become rigid, often leading teachers to feel like there is no room for their own authority and agency. It is no easy task to find the right balance between a consistent approach to instruction and trusting teachers to be intentional decision-makers. Despite this challenge we must beware of the person who has “the right answer” for every single classroom as it really does not exist.

The Effect for Students: Teacher’s guides make all sorts of assumptions about what students need each day that rarely match the reality of classrooms. Students are learning strategies that are too advanced for where they are just yet, or they are wasting time being shown strategies they have already mastered without any clear purpose. Students begin to disengage and “check out” when instruction is clearly not aligned to who they are as people and readers. In the end, students don’t feel valued, known, or seen. Students show up to class with a “Just tell me what you want me to do” mentality.

The Effect for Teachers: We have sat with teachers from around the country who explain how uninspired they feel when they are handed a teacher’s guide and told to follow it page by page. Rightly so, when teachers work hard on planning lessons they are told to teach and the lesson totally misses the mark, teachers feel disappointed, frustrated, and it reinforces the mindset of mistrust. In the end, teachers do not feel successful, hopeful, and valued. Teachers show up to class with a “Just tell me what you want me to do” mentality.

The Solution: Teachers must be trusted to use information about their students as the data that informs each day’s instructional decision. For example, if Juan can learn information from the photos in his nonfiction book, but skips all the hard words, his teacher, Maria, will likely decide to teach him how to figure out those complex words. No teachers’ guide will tell Maria what exactly Juan needs. Only Maria, sitting next to Juan each day, will ever know what’s right for Juan. In the most effective reading classrooms, student observations become the next day’s lesson plans.

Mindset of Trust: The more local the decision-making happens, that is, the closer to the student the decision maker is, the more effective it will be. When teachers are trusted with decision-making, they are four times more likely to believe they can make a difference (Quaglia & Lande, 2016). Teachers must be viewed as decision-makers with the knowledge, expertise, and context to know what their particular student readers need next. We can all help create this much-needed mindset of trust.

Reference:

Quaglia, R.J. & Lande, L. L. (2016). Teacher voice: Amplifying success. Thousand Oaks,CA: Corwin Press.

Response From Tan Huynh

Tan Huynh is a Teach For America alumnus and the head of the English Language Acquisition Department at Vientiane International School, an International Baccalaureate World School. He shares his classroom-tested, research-supported strategies on his blog:

Often, reading instruction is like a cake laid before judges at a baking competition. It’s tested, probed, questioned, ranked, and scored. Well-meaning teachers spend so much time designing and sequencing well-crafted questions to assess comprehension and elicit critical thinking.

This is a mistake.

Offer Process-Based Reading Instruction

Reading is more about the process than the product. If students don’t understand the text, then asking the most thoughtful question is fruitless. Therefore, the biggest mistake of reading instruction is thinking that reading should be an outcome tested rather than a process experienced.

We need to teach students how to interact with the text, not worry about how we’re assessing it.

Recognize the Two Levels of Reading

- Understanding what happened and

- Understanding the meaning of what happened

Students must first comprehend the text before they can analyze it. To develop their comprehension, we need to teach them strategies for constructing meaning. To show how, I’ll use this text from the Guardian as an example:

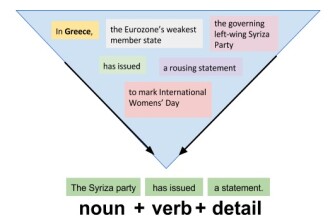

“In Greece, the Eurozone’s weakest member state, the governing left-wing Syriza Party has issued a rousing statement to mark International Womens’ Day” (Smith, 2017).

Teach Sentence Deconstruction

Model the process of deconstructing this complex sentence:

- Read aloud one section—stopping at punctuation

- Identify the facts

My students usually report that the author wants us to know that something is happening in Greece. When I ask students what new information they learned from before the second comma, they say that among the states in the Eurozone, there’s one that’s weakest.

- Connect the dots

I instruct the students to take the “In Greece” part and connect it to what we just read. When students combine the two sections, they realize that Greece is the weakest state in the Eurozone.

- Repeat Steps 1-3 until the full-stop.

- Identify the verb and its subject

I ask students to find the verb, and they identify, “has issued"; to which I ask “Issuing what?”. Students respond that a statement has been issued. Then I guide them to find who or what organization is issuing the statement. They identify that it was the Syriza Party.

- Simplify the Sentence

Once we deconstruct all the essential parts of this sentence, I asked students to simplify the sentence, putting together its essential components in this order: noun + verb + detail.

My students are able to reconstruct the sentence to mean that the Syriza Party in Greece issued a statement. By modeling how proficient readers interact with the text, we can empower ELs to independently construct meaning.

Spot the Signposts for Analytical Reading

Just like how the majority of an iceberg is unseen, a text’s deeper meaning lies beneath its literal details. Analytical readers pay attention to things such as characterization, literary devices, different perspectives, repeating symbols, and figurative language as seen on the infographic below:

As I read aloud a piece of literature, I will:

Stop at a point in the text when a symbol we’ve seen before reappears.

Point out to students that sometimes when we see a symbol or color showing up repeatedly, it might be of significance.

Reread a section of text to find the repeated symbol, and then

Discuss its meaning to the text.

For example, in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, I have them focus on the color red. By paying attention to what happens to a character when red shows up and what events or objects are associated with red, they learn to infer the meaning of red in Morrison’s novel. Once students become more competent at spotting these signposts, I withdraw my prompts. When I read a section of text aloud and pause to ask, “What details do you notice?”, without fail, student mention the items on the Literature Iceberg.

Describing reading as a finished product is the biggest mistake well-meaning educators commit when teaching reading instruction. We need to shift away from asking questions that test comprehension and shift to demonstrating how meaning is constructed. Additionally, we have to raise students’ awareness of the deeper analytical signs critical readers keep on their radar.If we honor reading as a process to experience, students will abandon the belief that some are born as proficient readers while others are doomed to grasping at words

Smith, H. (2017, March 08). International Women’s Day 2017: Protests, activism and a strike - live.

Response From Samantha Cleaver

Samantha Cleaver is a doctoral candidate in special education at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and the research assistant with Read Charlotte where she is focused on improving 3rd grade reading outcomes. She is also the author of articles for teachers on topics from teaching close reading to encouraging high-achieving students. Her book, Every Reader a Close Reader: Expand and Deepen Close Reading in Your Classroom, was published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2015:

Take the Time to Build Bricks

Look around any classroom and you’ll see students with a range of reading skills—students who are strong, avid readers; those who have figured out what they need to do to get by; and those who struggle to “get the words off the page.”

Thinking about that classroom using the analogy of the Three Little Pigs, each student has a reading “house.” Some of those houses are made of brick—think students that have strong skills that will help them read any book. Some students have houses made of sticks—not perfect, but they will do for now. And, some students have houses made of straw—flimsy and weak, their skills are not strong enough to help them tackle even the most basic reading tasks.

There are students in every grade who are working with straw; the mistake that teachers make is spending more time trying to cover the straw using interventions that have not been proven effective, rather than building bricks by shoring up students’ reading skills through the use of evidence-based practices (EBPs).

Making Bricks

Evidence-based practices are those that have been proven effective with struggling readers through strong research (Cook & Cook, 2011; Cook & Odom, 2013). These are important for struggling readers—those students living in straw houses—because these students need instruction that accomplishes more in less time. Online clearinghouses like What Works Clearinghouse (https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/), Best Evidence Encyclopedia (www.bestevidence.org), and the new Evidence for ESSA database (www.evidenceforessa.org) are designed to give teachers information about the programs they use or want to use. With evidence from WWC, for example, for a child who needs to work on phonics and word reading, choose a proven program like Sound Partners (an intervention for early reading) over another, perhaps more popular, intervention.

Finding and figuring out how to implement EBPs may sound tedious, but it is time well spent. To be sure, the most valuable commodity that teachers have is time, and interventions with strong research support are those that will have the greatest impact in the shortest amount of time.

Returning to the Three Little Pigs, students with straw houses—those who struggle to learn to read—need focused, systematic interventions (Fuchs et al., 2015) now more than ever. These students don’t need just a load of bricks, but an expert bricklayer to help them create better houses at a faster pace and with more precision than students who have mastered reading skills. Teachers can pull evidence-based practices to address the needs of struggling readers, and help all students build a house of bricks.

References

Cook, B. G., & Cook, S. C. (2011). Unraveling evidence-based practices in special education.

The Journal of Special Education, 47, 71-82. doi: 10.1177/0022466911420877

Cook, B. G., & Odom, S. L. (2013). Evidence-based practices and implementation science in

special education. Exceptional Children, 79, 135-144.

Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Compton, D. L., Wehby, J., Schumacher, R. F., Gersten, R., & Jordan,

N. C. (2015). Inclusion versus specialized intervention for very low-performing students: What does access mean in an era of academic challenge? Exceptional Children, 81, 134-157. doi: 10/1177/0014402914551743

Response From Jeffrey D. Wilhelm

Dr. Jeffrey Wilhelm is currently Distinguished Professor of English Education at Boise State University and regularly teaches middle and high school students. He is the founding director of the Maine Writing Project and the Boise State Writing Project, and author of 32 texts about literacy teaching and learning. He is the recipient of the two top research awards in English Education: the NCTE Promising Research Award for “You Gotta BE the Book” (TC Press) and the Russell Award for Distinguished Research for “Reading Don’t Fix No Chevys":

The biggest problem with reading instruction: We DON’T TEACH reading (beyond decoding)

It sounds provocative, I know: but data on classroom instruction indicates that teachers rarely ever actually teach reading—at least after second grade. And reading is way more complicated than almost anyone, even teachers, seem to think. We assign and assess, but as students move through their schooling, teachers rarely ever actually get inside the reading process to model, mentor and monitor students’ strategic progress as they read more complex content in ever more complex forms of text.

Several years ago, I heard the famous reading researcher Dick Allington speak. Based on his review of research, he argued that American schools tend to stop teaching reading after 2nd grade because we define reading as decoding. Two 2nd grade teachers were sitting in front of me. They began to whisper to each other. Then one of the teachers raised her hand and said: “We don’t teach reading in 2nd grade—we expect the 1st grade teachers to have done that.” Allington roared: “The problem is even worse than I thought!” His argument was that reading is much more than decoding, and is complex enough that the reading process needs to be actively taught and supported throughout the whole of schooling. Think about it. Students are taught how to decode very early in their schooling, while almost exclusively reading simple stories, and then are expected, entirely on their own, to learn how to use complicated strategies like inferring and identifying main ideas in a variety of expository and informational texts, as well as more complex narratives.

The Infamous Fourth Grade Reading Slump

The “4th grade reading slump” is a well-documented phenomenon (the term was coined by the researcher Jeanne Chall). In early grades, students generally demonstrate a strong enthusiasm for reading and a robust sense of self-efficacy as readers. But then, as my co-researcher Michael Smith and I found, they fall off the cliff right around 4th grade. In our study of the literate lives of boys one informant told us that “I used to be a pretty good reader, but then I just got stupider.” When we asked when he got stupider, he replied, “Pretty much right around 4th grade.” Well, certainly this young man did not get stupider. What did happen was that the reading he was asked to do suddenly became markedly more difficult. In early grades he was primarily reading straight narratives, typically supported by pictures and other visuals. Narrative, as the brain researcher Barbara Hardy maintains, is the primary mode of mind. Then, around 4th grade, students are asked to read informational text structures, often in textbooks (the densest source of information known to humanity!), and to make matters worse these structures are often embedded one in another. At the same time, a double whammy: even the straight narratives kids read in early grades get more complex with chapter books including symbolism and subverted by irony or unreliable narrators and unreliable characters.

Teaching general process strategies of reading is a big help: activating prior knowledge, predicting, summarizing, questioning, monitoring, etc. because these strategies are used by every successful reader every time they successfully read. Though these strategies are necessary to all comprehension, they are insufficient to comprehending more complex texts in various genres. For that, readers need task-specific strategies for noticing and interpreting elements that can appear in any more complex text, things like unreliable narration or symbolism. As Smagorinsky and Smith have eloquently demonstrated, readers also need text-specific strategies for noticing and interpreting the navigational devices used by specific genres like arguments of judgment and embedded text structures like comparison or definition.

The National Assessments of Educational Progress (the NAEPs)

The abstract of the reading section of the 2013 NAEPs reports that: “A full 25 percent of 12th-graders in 2013 scored below basic, compared with 20 percent in 1992, and just 37 percent scored at or above proficient, compared with 40 percent in 1992. Those scoring at the proficient level could answer questions requiring them to recognize the paraphrase of an idea from a historical speech and the interpretation of a paragraph in such a speech.” When it came to inferring across a longer text, or reading for a main idea across a more complex text or data set—and then explaining and justifying that main idea, the number of graduating seniors who were proficient was in the single digits. This trend goes back to the 1990s.

What’s at stake?

There is a lot at stake here. This is not only a crisis in literacy, this is a crisis of civil rights and a threat to democracy. Think about it: If only 37 percent of our graduating seniors can read at the literal and simple interpretive level, and if fewer than 10 percent can elicit and justify a main idea from complex text, then all they can do is repeat the literal information they read or are told. They are not able to construct or critique meaning through text, and cannot think with or about text. And that means that students cannot actualize their full potential as human beings. They cannot participate mindfully in a democracy as an informed citizen. If I were living in Canada I’d be making a call to build a border wall!

What to do

We need to teach reading and composing at every grade level and in every subject (as is actually required by law in states that have adopted the Core, the NGSS and many other next generation standards documents).

How to do it: Teach students how to use rules of notice

Reading is knowing what to notice, and then knowing how to interpret the patterns of key details or features that have been noticed.

In our recent book DIVING DEEP INTO NONFICTION, Michael Smith and I promote four aspects of text that expert readers always notice and attend to: topics, key details, genre (macro-structures), and text structures (micro embedded structures). They notice these elements in order to deeply understand how content and textual structuring work together to express meaning and effect. We highlight four kinds of rules of notice that guide noticing and interpretation of these textual aspects: direct statements/generalizations, calls to attention (thing like titles and italics, but also figurative language, repetition, etc.), rules of rupture (surprises and shifts), and rules of readers’ response (the reader’s agreement, emotional charge, questions, etc.).

Thinking aloud to model and teach expert reading

We provide seven different instructional strategies for modeling and then mentoring students into deliberately practicing how to read complex text written in different structures. One of these strategies is “Thinking aloud” which is a way for teachers to discover their own expert reading strategies, and then to deliberately model, then mentor and monitor students in mindful and deliberate practice using the rules of notice. As they do this, students are developing and consolidating many reading strategies that are also powerful cognitive and problem-solving strategies.

The power of instructing with think-alouds is in the deliberate and concrete modeling: demonstrating how to notice that a strategy is called for, enacting the strategy in a context of real use (not a worksheet), and in monitoring lapses and navigating the inevitable fits and starts involved in expert reading. Teachers extend learning by mentoring and monitoring students’ deliberate practice with the same focus strategy (like inferring, or using the topic-comment strategy to read for main idea) as they think aloud. Through such deliberate practice students can learn how texts are structured to communicate particular meanings and achieve certain effects. By mindful teaching and deliberate practice with noticing and interpreting we can solve the problems of not teaching, and of students not learning how to read complex text.

On a typical day, I might spend the morning teaching 4th or 7th graders, then move to a university undergraduate methods students in the afternoon, then teach highly accomplished teachers and graduate students at night. These are very different populations with some very different needs. But they all share this same common problem: they are all faced with texts they do not YET know how to read. These texts are complex and can be very opaque in their operation. For example, the 5th graders might be reading scientific graphs, or stories with a twist. The undergraduates might be reading a research brief. The graduate students might be reading abstracts and literature reviews. So what follows? I have to teach them how to recognize the features and demands of the challenging text they now face, then model and mentor them into using the kinds of specific stances and strategies necessary to navigating and reading that particular kind of text. If I do not, they will struggle and probably not achieve conscious competence with expert strategies, and they will be denied the conscious strategies for composing this same kind of text. It is therefore incumbent upon me to explicitly teach them how to do so.

Response From Emily Geltz

Emily Geltz is a 6th grade ELA teacher at Oyster River Middle School in Durham, NH in her fifth year of teaching:

The biggest mistake teachers make in reading instruction is teaching reading as a series of separate parts instead of the whole. I am guilty of this. Every year, I looked at the Common Core State Reading Standards and tackled them one-by-one. For a few weeks we worked on identifying theme, for a few others we explored character development. I was so confused with why my students didn’t seem to be making progress in their development as readers. Wasn’t I teaching exactly what I was supposed to?

Then I took a class with Vicki Vinton and read her book Dynamic Teaching for Deeper Reading. She had us take a look at our own reading process and use what we learned to teach reading as a whole. I realized that literary terms are abstract, kids should experience reading first before the concepts are named.

I learned that reading is as much of a process of drafting and revising as writing is. In the beginning of books, we are trying to figure out what kind of world we are in, who the characters are, what is happening. Reading is the thought behind being able to make meaning and figure these things out as a whole&madsh;not thinking individually about theme or character development. We think about what things in stories “might be” and we revise our thinking if something proves us wrong. We find patterns authors left for us in our reading that allow us to identify a bigger message.

Teaching reading as a whole allows me to teach reading authentically and it makes so much more sense.

Response From Sarah Shanks

Sarah Shanks and I has been an EAL (English Is An Additional Language) teacher for over 15 years. She has worked overseas, mainly in Asia, and is now Head of EAL at Warminster School in the UK. Her EAL passion is finding new and exciting ways of engaging EAL learners:

In preparation for answering this question, I looked at my own biggest mistake when teaching reading—too much teacher talking. On reflection, I may introduce a reading text or topic and find myself talking and explaining it before the students have had a chance to get to grips with the text. Therefore I would suggest the following to ensure that teacher talking is kept to a minimum.

Firstly, teachers need to consider the topic of the text and the students’ previous knowledge of the topic. I tend to teach students of different cultures. This alone means that consideration has to be given to reading topic choices, as the teacher wants to educate the students but also not cause offence, especially when dealing with topics which could potentially cause a lot of class discussion. However, the teacher also wants to provide reading topics which are going to spark interest. The teacher also wants to ensure that the topic isn’t so far out of the students’ range that they spend more time explaining it that than the students do reading about it.

Secondly, when the students are given the text, it is vital for the teacher to step back and allow the students to digest the material. Again, to ensure that my talking time is kept to a minimum, I provide the students with just the heading, sub-headings and any pictures. From this minimal information, the students are then able discuss what they think the article will be about and brainstorm the key vocabulary that they would expect to read. Furthermore, they can discuss what type of information to expect within the text, for example any research, historical data or assumptions, which will in turn guide the students in regards to the grammar being used.

Finally, once the reading text has been read, the teachers need to give the students time to reflect and feedback on the text. This could be done in a number of ways, for example looking for topic-related texts from their own countries or cultures or from current media or preparing presentations or debates about the topic read.

Thanks to Gravity, Renee, Tan, Samantha, Jeff, Emily and Sarah for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo.

Anyone whose question is selected for this weekly column can choose one free book from a number of education publishers.

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching.

Just a reminder—you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email or RSS Reader. And, if you missed any of the highlights from the first six years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. They don’t include ones from this current year, but you can find them by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Best Ways To Begin The School Year

Best Ways To End The School Year

Student Motivation & Social Emotional Learning

Teaching English Language Learners

Entering The Teaching Profession

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributers to this column.

Look for Part Four in a few days..