While it might not signal the breakdown of the social compact, the fact that scarcely more than a third of all Detroit high school students graduate indicates that all is not well with America. (Diplomas Count, June 5, 2008.) We are not all Detroit, but the problem is everywhere, and the fact that dropouts often opt out of society as well adds to our concern. Theories and remedies abound, usually centered around the quality of instruction, student motivation, the home, poor facilities, and inadequate supplies.

All these elements play a role, and yet there must be more. Failure also touches large numbers of students who attend well-appointed schools, who come from stable families, and who are anxious to complete their education.

I believe we should also be looking at the traditional high school curriculum, which in large measure has little relevance to anyone—dropout or not.

How many of us remember much of Euclidian geometry, logarithms, or trigonometry? Would we trust ourselves to calculate the interest of a loan over a period of time?

There are powerful outcomes associated with a three-year sequence of secondary mathematics. Students develop intellectual skills, powers of abstraction, a sense of confidence in moving from simple procedures to problems requiring the application of principles to new situations. There is personal growth and a sense of achievement, among other outcomes that transcend the content but include transferable skills so important in later life.

High school mathematics accomplishes all this—and those students who successfully master the subject are certainly the better for it. But is it necessary?

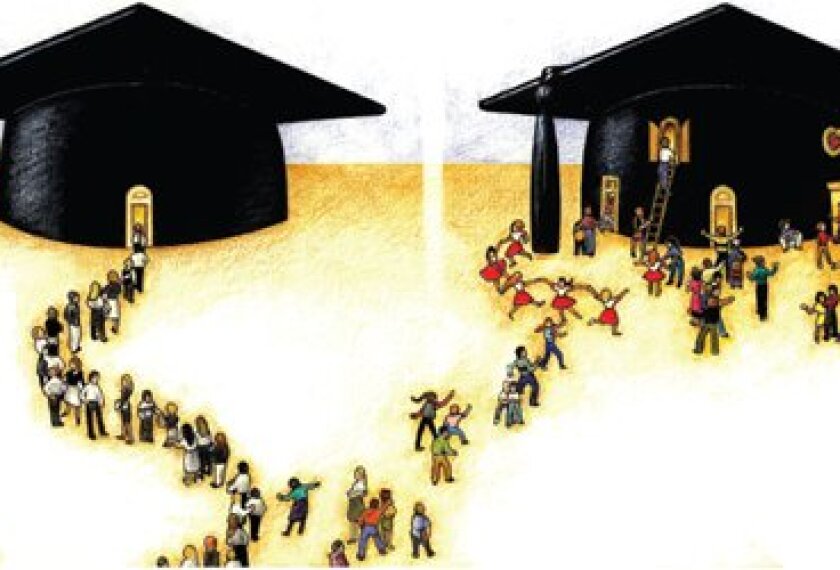

We have created an educational structure that is convenient for government, convenient for teachers, and convenient for society— but seemingly highly unsuitable for many young people.

Is it possible to achieve such qualities of mind in some other way? Are there other content areas that could also serve, yet be more relevant, more accessible to students?

There was a time when content was important for itself, and precedent played a major role in determining what was to be taught in high school. But the Internet has changed everything.

Thus, the facts of history are no longer the province of the scholar alone. A few clicks of the mouse produce what 35 years earlier was the acquisition of knowledge of a lifetime. We must seriously re-examine the role of history in the high school curriculum, particularly since so many students who go on to college also display a lack of knowledge of the basic chronology of events. This, in spite of an intense focus on their knowing what happened, when, and by whom.

Maybe high school students should learn how to evaluate facts, to place them into perspective, and to detect trends. The student of history examines influences, causes, and reasons for success; he or she notes patterns that can help society avoid errors of the past. Perhaps students need to learn to see broad schemes that transcend centuries to appreciate structures and place ideas and facts in context.

This is not to say that such an approach would guarantee more successful learning outcomes. But such alternatives are certainly worth examining.

Curriculum is not dogma. In the same way that colleges re-examine their offerings periodically, secondary schools should review their mandates regularly and dispassionately. We should all welcome experimentation, and acknowledge successful alternatives.

As it is, we have created an educational structure that is convenient for government, convenient for teachers, and convenient for society—but seemingly highly unsuitable for many young people. We must keep in mind that the frustration which brings a student to leave school is often accompanied by a disavowal of community and its norms. Is this not a possible source of our unemployed, our unemployable, our young people in the streets?

Admittedly, we cannot create a separate school for each student. And removing mathematics, for example, from its place in the secondary school curriculum would cause immense dislocation. But no, it would not hamper our efforts to remain scientifically and technologically advanced. The students who must be forced into the K-12 mathematics box are not the ones who will go on to careers in science and technology. Far better to seek out those with a propensity for math and raise them to international standards, and help others succeed in different areas of learning.

Perhaps a more promising model is that of postsecondary education. There have been marked changes in the standard college curriculum—indeed, so different are the courses as to call into question any orthodoxy with respect to course content at any level. American history has been replaced in many instances by a more global approach to the development of civilization. And the classics of English literature no longer rule: Area studies have sometimes replaced specific core courses as a platform to develop ideas and foster intellectual, critical-thinking skills.

The study of French gave way to Spanish, which in turn is being replaced by Arabic and Chinese. Yet the college degree has not been cheapened in any way. Quite the contrary, we have increasingly discovered that the quality of a college experience is largely content-independent.

Different content requirements, different emphases, different distributions are all part of that marvelously heterogeneous, unorganized panorama that is American higher education. This is why colleges flourish, and this is one of the reasons independent high schools generally serve their students so much more effectively than do public schools. Public secondary education, on the other hand, generally offers a rigid, largely one-size-fits-all, and unchanging curriculum.

There was a time when content was important for itself, and precedent played a major role in determining what was to be taught in high school. But the Internet has changed everything.

The diversity of learning at the college level is at times breathtaking, with initiatives taking advantage of changing demographics as well as changing technology (producing superb engineers whose training never required them to lift a soldering iron), changing needs (a regionally accredited college offering a work-related baccalaureate degree in 28 months), changing theories (the Bologna Accord nations’ three-year curriculum), and changing population patterns (the delivery of courses online).

And we should certainly be taking note of the vastly changed 14- to 18-year-old cohort that occupies our nation’s high school desks. In sophistication, exposure, experience, and self-image, this group is entirely different from the high school body of a generation or more ago.

Even as we consider moving away from a single secondary curriculum, we must be aware that high school students, or their families, may not be able to make as wise a selection of courses as do college students. But this is only one facet of a large question that deserves to be placed on the table.

In addressing this question, we must be certain to seat everyone around that table. Educators, of course, but not educators alone. Those who know how to teach are not always the ones who know what to teach. We need people who have succeeded in life in spite of a bad secondary school experience, and high school successes whose careers were not particularly rewarding ones. We need experts who will advocate for the status quo, as well as those who will ask searching questions.

This is not a call to dismantle ongoing, successful (even moderately so) systems. It is a call for a new sense of openness, of flexibility, of engagement in a healthy examination of policy and practice where there is no success.

It is a call, too, for experimentation, and for diversity where there has been evidence of success. And it is a plea for the recognition of alternatives that may or may not be part of the canon.