A not-so-funny thing happened on the way to creating a new award to honor high schools that do a good job preparing students for college: It became impossible.

GreatSchools, an organization that gathers and shares school information to inform parents, wanted to confer its new “College Success Awards” on schools in every state. But a lack of data forced the organization to scale the awards down to just nine states.

In a report released Thursday, GreatSchools lists the 814 winners of its new award, but also describes the difficulty it had assembling all the information it considers necessary to paint a meaningful picture of how well high schools are doing.

In a call with reporters, GreatSchools Chief Strategy Officer Samantha Olivieri said the report celebrates the good work in schools, but also serves as a “call to action” to states to publish a wider variety of metrics, all in one place, to provide parents with “a more complete picture of high school quality.”

Data Missing in Most States

The idea behind the new award was to tell a more detailed story about schools than standardized test scores can convey. GreatSchools judged schools in three categories: how well they prepared students for college, as judged by SAT or ACT scores; the percentage of students who enrolled in college, and how well the students performed once they got there. For this last metric, GreatSchools relied on remediation rates and the numbers of freshmen who stuck around for a second year of college.

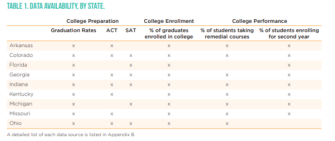

Trouble is, data in all three of those categories were available for only nine states: Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, and Ohio. (Oklahoma, Connecticut, and Minnesota eventually supplied GreatSchools with all the data, but too late to include schools in those states in this year’s awards.)

Olivieri said that of the three categories of data GreatSchools was searching for, information on college remediation and persistence was the toughest one to find. That could be because states aren’t required by federal law to include it on state report cards, she said.

A new requirement in the Every Student Succeeds Act requires states to report, on a school-by-school basis, the percentage of students who enroll in college, if that information is available. In a report last year, the Data Quality Campaign found that college enrollment numbers are indeed readily available to states, and 45 collect and publish them. But only 17 publish them in their school report cards, where parents are most likely to search for information about their schools.

Even among GreatSchools’ nine winners, missing data led some states to be judged on only one data point while others were judged on two. In Florida, for example, college performance was judged on the basis of persistence data, while in Ohio, that category was judged only on the basis of remedial rates.

GreatSchools acknowledged that the winners represent a disproportionately low share of schools with high poverty rates. Only 20 percent of its winners are schools where 40 percent or more of the students quality for free or reduced-price lunch.

The organization surveyed winners to find out what they’ve been doing that might explain their success in not only preparing students for college, but also helping those students do well once they’re on campus. It released videos and articles profiling some of those schools.

It found that its award winners were more likely to provide rigorous academic offerings, both in school and outside of school, and to have systematic ways of identifying and supporting struggling students. They also have “robust” staffs of guidance and college counselors.

But GreatSchools officials used the awards announcement as a platform to make a plea to states to report a fuller set of data to families. It’s particularly important, they said, that every school report data that show how well students do in college.