Many children whose parents didn’t go to college aim for degrees in higher education, but they’re far less prepared to go to college than their peers who grew up with college-educated parents, according to a new report.

The Condition of College & Career Readiness 2014: First-Generation Students, released last month by ACT and the Council for Opportunity in Education, repeats what we’ve long known: Family education background exerts a powerful influence on students’ readiness for college. But a look at the hard numbers is a bracing reminder of how much support first-generation college students need, and how often our schools are falling short of providing it.

Looking at the “first-generation” students—the students whose parents didn’t go to college—you can see right away how they’re a step behind their high school classmates. Ninety percent of the first-generation students who took the ACT said they planned to go to college, but 52 percent didn’t reach a single one of the score points on the ACT that are associated with the likelihood of success in college. In the bigger pool of all students who took the ACT in 2014, 31 percent failed to reach any of those “college-readiness benchmarks” on the test.

Only 9 percent of first-generation students meet all four of the college-readiness benchmarks, and the trend line isn’t promising, either: It’s been stuck at 9 percent since at least 2011. Even worse, the proportions of first-generation students who have met the benchmarks in English, reading, and math have declined in the last four years. There is one bright spot: More first-generation students are reaching the college-ready score in science—from 12 percent in 2011 to 17 percent in 2014.

The flat or declining trend lines could be explained in part by the diversifying pool of test-takers. As greater numbers of traditionally underserved—and typically more academically struggling—students take such tests, the overall scores drop. And the numbers of first-generation students taking the ACT has indeed been rising, from 10 percent of the overall pool in 2011 to 18 percent in 2014, according to the report.

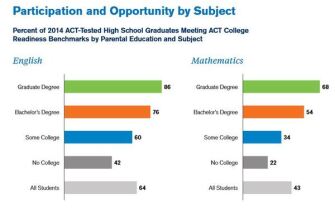

We know that parents’ educational attainment predicts students’ achievement, but this chart from the ACT report drives the point home in bold and painful ways.

Knowing what we do about these patterns, one can’t help but wonder whether flagging parental education level as an early warning indicator for students could bring additional resources to bear. Six years ago, I wrote about Chicago’s work to have middle schools send signals to their high schools about each rising 9th grader’s risk factors, on the theory that the students who are at high risk could get additional academic and counseling support as they enter high school. The risk factors they used included grades, attendance, and behavior. But what if we used parental education level in a similar way, as part of a needs profile for students?

As the ACT report—and many other reports—point out, students who start early with rigorous coursework are more likely to be well prepared for college and work. Of course, they need the right supports in school to encourage them to take such courses, and help them through the rough parts. And providing the right supports often proves more difficult for schools than identifying the students who need them.

The first-generation report is one piece of a flurry of reports that ACT produces on the college-readiness of students who take its signature college-admissions test. Click here for the overall national profile of test-takers, and here for a state map that you can use to examine trends and profiles for each state. There are also reports that focus on Hispanic and American Indian students, and on students who express an interest in careers in education.