Students in U.S. urban school districts are the latest to have their academic skills measured on a global scale in a study that shows them achieving mixed results when judged in math against their counterparts in foreign nations.

Children in American cities generally fared better at the 4th grade level in the global comparison, and performed more unevenly in 8th grade, according to the analysis, published last week by the Washington-based American Institutes for Research.

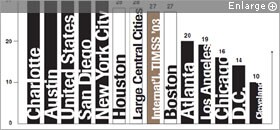

Six of the 11 U.S. city school systems evaluated performed at or above the average for developed nations in 4th grade mathematics, according to the study. Yet only two of the 11 districts—Charlotte-Mecklenburg, N.C., and Austin, Texas—reached the 8th grade international average for developed nations.

The study statistically links urban districts’ 2003 scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress with country-by-country results from the same year on the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study. After linking those test results, the authors compared the TIMSS scores against the 2007 NAEP Trial Urban District Assessment, as well as overall state NAEP results, which provide national U.S. averages.

In addition to Charlotte-Mecklenburg and Austin, other districts in the study are Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles, New York City, and San Diego.

Four big-city districts performed signiicantly better than the overall international average of 24 countries at the 4th grade level. Five performed below the international average.

SOURCE: American Institutes for Research

The study compares the percentage of U.S. and international students reaching the NAEP “proficient” level in math in grades 4 and 8.

Holding American students to a high bar is crucial, the authors argue.

The international workplace demands that an American student perform at a mathematically “proficient level, at the minimum,” they write, or he or she will face a “quantitative headwind in his or her adult life.”

The report was written by Gary W. Phillips, a chief scientist at the AIR, a nonprofit, independent research group, and John A. Dorsey, a professor of mathematics at Illinois State University in Normal. It is a follow-up to a 2007 analysis Mr. Phillips conducted, which compared individual U.S. states with foreign nations, using the same methodology but different data.

8th Grade Drop-Off?

U.S. urban students fared relatively well when compared against both industrialized and developing nations that took part in TIMSS, Mr. Phillips noted in an interview. But when compared with students just in industrialized countries—those with economic conditions similar to those of the United States—American students’ showing was not as strong, a finding that should trouble policymakers, Mr. Phillips said.

In a separate measure of the entire U.S. student population, 4th graders were more successful against developed nations in math, topping the international average, the study found. But U.S. 8th graders did not do as well, performing at roughly the same level as the average for industrialized nations.

In explaining 8th graders’ relatively poor performance, Mr. Phillips said it was possible that they simply didn’t match up as well academically as 4th graders in the international comparison. But it also could be that the 8th grade proficiency standard on NAEP was higher for 8th grade than for 4th grade. Federal officials score those students on different scales, Mr. Phillips pointed out.

Michael D. Casserly, the executive director of the Council of the Great City Schools, said he wished the study had documented the strong gains made by city districts on the trial urban NAEP, which his Washington organization was instrumental in creating. The value of the urban NAEP is that it provides school officials with data to gauge improvement, rather than pitting them in a “horse race” against nonurban or foreign students, he said.

While calling the international study “interesting,” he said he wasn’t sure it would shape policy in big-city districts in the way that other analyses might.

It’s difficult “to know what to do with these results,” Mr. Casserly said. “If you’re [a district] above Latvia, and you’re below Hungary, what do you do?”