Charter school teachers tend to have fewer years of experience, and work longer hours than their counterparts in public, non-charter schools, a new analysis suggests.

Yet by another measure—the hiring of teachers from “highly selective” colleges—both charters and traditional public schools lag well behind the private school norm.

Many of those findings are consistent with past research, notes the author of the paper, Marisa Cannata of Vanderbilt University, whose work is included as part of a newly published book, Exploring the School Choice Universe: Evidence and Recommendations. But the analysis provides fresh insights into who goes to work in public and private sector schools, and what kinds of conditions they encounter when they get there.

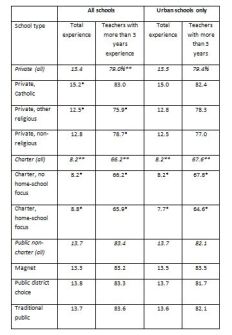

Cannata, who culls data from the federal Schools and Staffing Survey, finds that charter schools, both in urban and non-urban areas, employ a smaller percentage of teachers with more than three years of experience on the job than do both regular public and private schools:

One asterisk means the results are significantly different from the length of time on the job among teachers in traditional public schools; a pair of asterisks means the results are significantly different from public non-charter schools.

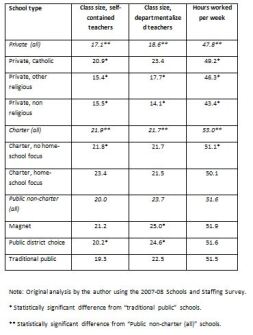

Teachers in charters also tend to spend more time per week on the job than their non-charter public school peers—and on average, their hours also exceed those put in by their private school counterparts by an even greater margin:

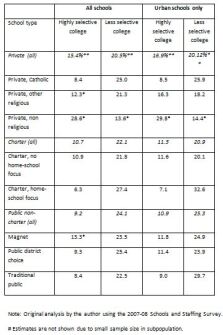

What are the educational backgrounds of teachers working in charters, private schools, and regular public schools? The paper finds that nearly 11 percent of charter-school teachers are likely to have attended “highly selective” colleges, and 8.4 percent of traditional public school educators did so. Public magnet school teachers, meanwhile, were more likely than either group to have attended a top-ranked college. (Cannata uses Barron’s rankings of colleges, which in turn are based on undergraduate admissions data, for this part of the analysis.)

But by far, the teachers most likely to have attended elite colleges are those working in private, non-religious schools, with nearly 29 percent having done so. Interestingly, teachers in one class of private schools—Catholic schools—were not nearly as likely to have attended a highly selective institutions. Only about 8 percent have that educational background.

Cannata speculates that these numbers may say more about non-religious private schools’ hiring priorities than they do about those of Catholic schools. Catholic and regular public schools today are likely to hire educators from a similar pool of individuals who have been trained through teacher-education programs—presumably while attending colleges that, whatever their merits, don’t fall in the highly selective category.

Many non-religious private schools, on the other hand, serve a relatively affluent population of parents who assume that their children are bound for elite colleges, Cannata suggested in an e-mail. As a result, leaders of those non-sectarian schools may be more inclined to place an emphasis on hiring teachers from the most selective colleges, she says. (If readers have an alternate explanation for the disparity between Catholic and non-Catholic private schools in this area, feel free to send them along.)

Of course, it’s reasonable to question whether having attended a “highly selective” college matters to teachers at all. Educators are judged not just on what they know, but on how well they can impart that knowledge to students, including those with very different sets of abilities.