A recent book assembles a collection of studies on one of the great mysteries of contemporary American education: Why did national progress in narrowing the achievement gap separating African-American and white students stall from the late 1980s until 2004?

Steady Gains and Stalled Progress, published by the Russell Sage Foundation of New York City, offers no solid answers to that question. But the volume’s studies do whittle down some popular explanations and point to a lineup of likely suspects.

“I don’t think they found the smoking gun,” said Derek A. Neal, a University of Chicago economist who has reviewed the research and studies achievement gaps. “But neither have I.”

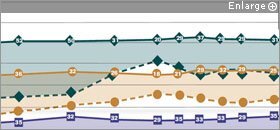

Scores on the long-term trend tests in reading and mathematics from the National Assessment of Educational Progress suggest that black children made strides in catching up to their white counterparts from 1975 until the late 1980s, but that progress then halted and remained largely stalled until 2004.

Reading

Math

Notes: Numbers on trend lines for white children represent gaps between their scores and those of black children at the same age.

Source: Russell Sage Foundation

The story of the black-white achievement gap is one of progress for most of the 20th century, experts say.

Long-term data from National Assessment of Educational Progress tests in reading and mathematics, for example, show that blacks made strides in catching up to their white counterparts from 1975 until the late 1980s. That’s when progress halted, remaining largely stalled until 2004, when results from the latest round of NAEP long-term trend tests suggested the gap might be narrowing again.

While federal education officials have attributed that uptick to the No Child Left Behind Act, most experts say more time is needed to tell whether those results mark the start of renewed progress or just a blip. Results from the 2008 long-term assessments are due out this spring.

Steady Gains and Stalled Progress, released in November, is among only a handful of research volumes to explore racial achievement gaps since 1998, when the book The Black-White Test-Score Gap by researchers Christopher Jencks and Meredith Phillips drew national attention to race-based patterns in test scores.

Like that influential predecessor, the Russell Sage Foundation book empirically explores various hypotheses for the test-score trends. Those possible explanations include: growing income inequality, differences in quality among teachers of black and white students, growth in racial isolation in schools, trends in parental education, and cultural differences.

“We were really trying to refocus attention on an issue that people hadn’t grappled with in a long time,” said Katherine A. Magnuson, an assistant professor of social work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She edited the book with Jane Waldfogel, a professor of social work and public affairs at Columbia University.

In his chapter, for instance, University of Virginia scholar David W. Grissmer argues that differences in the levels of skills—both cognitive and noncognitive—that young children bring to school might be at play.

Gaps at the Start

Science has long shown that strong academic skills and so-called “executive function” skills, such as paying attention or keeping information in mind while switching from one task to another, can predict children’s future academic success. But Mr. Grissmer’s analysis suggests that other kinds of school-readiness skills might be equally, or more, important.

In fact, he says, noncognitive and cognitive skills, taken together, might account for as much as one-third to one-half of the black-white test-score gap.

In particular, Mr. Grissmer points to fine motor skills—the ability, for example, to draw or use building blocks to replicate a model. Drawing on data from a federal longitudinal survey, he and his co-author find that black children’s fine motor skills tend to lag behind those of white children at the start of kindergarten.

The disparities are probably not genetically based, Mr. Grissmer says, because twins growing up in different families also show sizable differences in fine motor abilities.

“I think two things might be going on: You have to develop those things before you start school, and schools don’t address them very well,” Mr. Grissmer said in an interview.

Progress in closing the achievement gaps may have stalled, he surmised, because schools and preschools waged a “direct attack on cognitive skills in recent decades”—referring to ongoing efforts to teach academic skills, such as reading, at younger ages—“while ignoring the underlying building blocks that children need to master cognitive tasks.”

Education Levels Eyed

Trends in the numbers of black and white parents who go to college after high school also offer clues, several of the authors note.

“What happened was that during the original period of gap closing, black parents were making gains on white parents in terms of higher education,” said Ms. Waldfogel. “In the later period, both whites and blacks started increasingly to attend some college,” but at parallel rates.

Another possible explanation: the growing income gap, from the 1980s into the 1990s, between society’s haves and have-nots. But increases in income inequality, several authors say, may not play as big a role as some might guess.

In their chapter, Ms. Magnuson, Ms. Waldfogel, and their co-author contend that growth in income disparities over that period depressed test scores for both black and white 9-year-olds at similar rates. If income inequality had remained at 1978 levels, they calculate, the average math score for that age group in 2004 would be only 1 test-score point higher than it was.

Likewise, differences in the quality of the teachers who teach black and white students don’t completely explain why the gap stopped closing, said Sean P. Corcoran, an assistant professor of economics at New York University. Using data from the latest round of the federal Schools and Staffing Survey, Mr. Corcoran and his chapter co-author discovered that, while it’s true that the average black student is statistically more likely than the average white student to have teachers who are inexperienced, uncertified, and unhappy with their career choice, that’s been the case for decades.

The quality of teachers teaching African-American students declined from the late 1980s into the 1990s only at the elementary level, but the black-white achievement gap was widest over that period in secondary schools, Mr. Corcoran said.

“We suspect that might have had something to do with class-size-reduction policies, which might have brought an infusion of less-qualified teachers,” he said in an interview. “That all happened at the elementary level.”

Trends in the racial composition of the schools that African-American students attend also seem to play a role in black-white test-score patterns, several of the authors say. But the extent of that role depends in part on the yardstick that researchers use.

In her chapter of the Sage Foundation book, Ms. Phillips, an associate professor of public policy and sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Mr. Jencks’ co-author on the 1998 book on test-score disparities, sifts through national data for any shifts in youth behaviors, such as reading habits and TV watching, that might explain the slowdown in the narrowing of the gap.

Both before and after the gap stopped closing, she found, black and white 13-year-olds spent similar amounts of time reading for pleasure and doing homework, and got into similar amounts of trouble at school.

Gaps in problem behavior among black and white 17-year-olds widened, however, between 1988 and 1994, mostly because of an uptick in the numbers of African-American students who reported getting in trouble in school. There were no changes over that time, though, in the amount of time 17-year-olds spent in leisure reading.

The bottom line, writes Ronald F. Ferguson, the faculty director of Harvard University’s Achievement Gap Initiative, is that “there’s not a single story of stalled progress.”

“But it’s a hopeful story,” he added in an interview, “because we can see clearly that the achievement gap and achievement levels are not written in stone, and seem to be responsive to a range of things we have done and can continue to do.”