As economic and political inequality grows all around us in America, we look to schools for help. Our leaders talk about it every day. Usually they say there should be opportunity for all Americans, and especially for all American children. President Barack Obama offered an example in 2009, early in his presidency:

“Providing a high-quality education for all children is critical to America’s economic future. Education has always been the foundation for achieving the American dream, providing opportunity to millions of American families, newcomers, and immigrants. Our nation’s economic competitiveness depends on providing every child with an education that will enable them to compete in a global economy that is predicated on knowledge and innovation.”

But stop and think about it. Creating opportunity and social mobility doesn’t reduce inequality. Education may help a child move up in the world, but the world they move up in is increasingly unequal. One child moving up means they get ahead of another child who must move down.

This may sound like heresy in a nation devoted to Horatio Alger. The “creating opportunity” platitudes are so pervasive that it can be unsettling to subject them to the kinds of critical thinking that we ask of our students. But take things step by step, and think about three different kinds of inequality:

- educational,

- economic, and

- political.

The exasperating story of America in 2015 is that schools can reduce the first kind of inequality (if we really want them to), but they can do little about the second or the third.

Educational Inequality

We know children start school unequal, with some having grown up thriving in supportive and stimulating environments that prepare them for success on Day One. Others come to school without those advantages, and start out behind. For one example of our work to reduce this kind of inequality, look to the U.S. Department of Education’s “Ready to Learn” literacy program.

We also know that children have deeply unequal schooling opportunities, with some attending high-quality schools with excellent teachers, engaged peers, and supportive communities. Other children attend schools segregated by race and income, surrounded by struggling peers and often provided with crowded classrooms, inexperienced teachers, and shoddy facilities. The Education Trust and others have long documented these disparities.

Increasingly in the United States, we respond to these inequities not by desegregating students, but by intensifying our expectations of segregated schools, especially segregated urban schools. Such schools must somehow perform like non-poor suburban schools or risk being closed, “turned around,” or replaced by similarly segregated charters. U.S. News reports that the Stanford University CREDO center’s most recent research on charter schools finds "[u]rban students comprise only a quarter of students nationally, but 56 percent of those enrolled in charters.”

Finally, we know that children come out of school unequally. Graduation rates vary by race, class and region. Test scores vary along the same lines: we often hear about “the achievement gap,” by which we mean test score inequality across racial, ethnic, and income groups. EdWeek reports that, as captured by the National Assessment of Educational Progress since 1971, the test score gaps shrank rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s, then grew in the 1990s before stabilizing.

Not a month goes by without someone claiming this or that educational reform will reduce educational inequality. The Civil Rights Project at UCLA has long documented the educational benefits of desegregating schools by race and class. Most recently, EdSource in California reported claims that Common Core State Standards will reduce the gap.

The most promising current effort to reduce educational inequality began in California last year. As we have often reported here, the state of California enacted a Local Control Funding Formula that steers money toward the students who will most benefit: low-income children, English Learners, and those in foster care. If we use these funds wisely, we will make progress toward reducing educational inequality in the state. That’s a big “if,” of course: Carrie Hahnel of EdTrust West reported that during the first year of implementation, many school districts tried to use the extra money to “back fill” losses incurred during the budget cuts of the Great Recession.

So, one cheer for schools: they can reduce educational inequality, if we really want them to.

Economic Inequality? Schooling Doesn’t Make Much Difference

But Americans are talking more about other kinds of inequality these days. Economists Emanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty have documented soaring economic inequality for years. It has gotten so bad that that even conservative Republican presidential candidates are expressing concern.

How might schooling affect that kind of inequality?

The usual explanation is that more education enables workers to become more productive, which helps them move up in the world because employers will pay them for that increased productivity. Thus, more schooling leads to higher pay, and enables the have-nots to become have-mores.

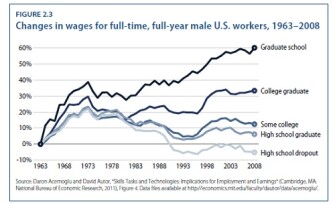

There is some evidence for some of this. A group of economists led by Larry Summers and Ed Balls recently led a “Commission on Inclusive Prosperity,” and the Center for American Progress published their report in January. The figure on the left, taken from their report, shows that workers with higher levels of education do indeed have higher incomes. On the other hand, look closely: for all but those with graduate degrees, wages have been stagnating since the late 1990s. And the data in this chart is from before the Great Recession.

This stagnation in American workers’ incomes is not because they haven’t been gaining education and becoming more productive. On the contrary, the blue line in the figure below, taken from Atif Mian’s and Amir Sufi’s blog “House of Debt,” shows that American worker productivity has increased more or less steadily since the late 1940s. Disturbingly, however, the red line in that graph shows median income for American families has been pretty much stagnant since the early 1970s in real terms, despite this increasing productivity. Workers are getting more education and producing more wealth, but they take home a decreasing share of the wealth they produce.

To put it bluntly, the link between worker productivity and worker income has been broken in the United States.

So no cheers for school there: schooling can’t stop the 1% from taking home virtually all the economic gains of recent years. Increasing the supply of skilled workers hasn’t increased the demand for them or their compensation. Economic inequality has increased even as schooling has improved.

Political Inequality? Schooling Doesn’t Help There, Either

Money isn’t everything, though, right? We still live in a democratic republic, where every adult citizen gets one vote, and civic engagement empowers people to govern themselves.

This is what scholar David Labaree calls the “democratic equality” goal of schooling in his recent books. Schools help children learn about their country, gain the skills necessary for effective civic engagement, and build personal commitments to participate in our public life.

You probably won’t be surprised to hear me tell you things aren’t so great on that score either. You don’t need someone from Occupy or the Tea Party to tell you that, although we have thousands of governments in the United States, the people running those governments don’t necessarily care about the civic engagement of ordinary people.

Political scientists Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page got on Jon Stewart’s program last year after publishing research showing how wealthy voices are pretty much the only ones heard in Washington, DC. In his 2012 book Affluence and Influence, Gilens found that

“On the policy questions on which low- and middle-income respondents’ ... views differ from those of more affluent Americans, government policy appears to be fairly responsive to the well-off and virtually unrelated to the desires of low- and middle-income citizens.”

To put things bluntly again, political power in the United States pretty much reflects economic resources. Growing economic inequality means growing political inequality.

So no cheers for school on this count: political inequality has grown even as schooling has improved.

What Should We Do, Then?

I don’t want this post to be a complete downer. I consider myself to be a fairly optimistic person. I’m old enough to have seen dramatic and constructive transformations in the world around me that have led to greater equity and more genuine equality: the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965; increased inclusion of disabled people in our schools and our public life; the fall of the Berlin Wall; the release of Nelson Mandela and the end of apartheid in South Africa; the legal freedom of lesbians and gays to marry those they love.

But none of those transformations were advanced by people who simply mouthed platitudes and kidded themselves about how the world works. It’s not enough to say “education is the civil rights issue of our time,” or that “children are our future,” especially if the one saying such things doesn’t come to grips with the growing inequality that undermines that future.

Public schools are important and we should support them. They deserve one cheer: they can give all children the best chance they’ll have to thrive in a difficult world. But while they can reduce educational inequality, under the current circumstances they can’t reduce economic or political inequality.

We have to stop averting our eyes and hoping schools will solve the problem for us. The only way to reduce inequality is to reduce inequality.

[This post draws on “Can Education Solve Growing American Inequality? Getting Beyond Platitudes,” a presentation I made at the Economic Inequality Forum at Pomona College in Claremont, California on March 3rd, sponsored by the American Institute for Progressive Democracy.]