This post is by Patrick Yurick, lead MOOC instructor for the High Tech High Graduate School of Education.

Deeper learning experiences are needed by our students. Not in two years, not in six months, and not next week. Deeper learning experiences are needed by our students today. This very moment. We need to structure environments where students are deeply engaged in their lives as they are living them.

I know this is true because during the last days of the 2010/11 school year, I experienced every teacher’s worst fear. My student was murdered. Sean and his younger brother Kyle tragically died in a murder/suicide, killed by their own father. Sean was my favorite that year. In fact, Sean was my favorite student of all time. He was the kid I wished I could have been at fifteen. He swaggered into school with confidence, intelligence, and a never-ending stream of comic book superhero references. Sean and I became close immediately. This closeness in our relationship only increased as we spent many hours together selling comics statewide at conventions in my after-school Graphic Novel Project.

I am still processing the fact that Sean’s death, which affected me so much as a person, has also affected my understanding of pedagogy. Deeper learning is a direction that feels right because it allows for a truly student centered pedagogy. Take this case in point:

On one afternoon session of the Graphic Novel Project I asked Sean along with two other students to generate four-panel funny strips. We were getting ready to attend a comic convention the following day to sell our comics and I wanted to try a new marketing gimmick to get customers to our student-run sales table. I told them to each make a black and white comic strip on a piece of copy paper. The funniest one would be the winner. “The winner of what, Yurick?” the kids asked. I told them to get to work so that they could find out. While the rest of the group was packing, the three team members in charge of marketing worked hurriedly on their comic strips. A half hour passed and I demanded to see the comics. Two team members handed me their strips. They were funny, but not what I was looking for.

Sean handed me his comic strip. At the top it said, “Muffin-Eats-Man.” Four panels were laid out. In the first panel a man was holding a muffin in his hand and both were looking at the reader (the muffin had eyes). In the second panel the man and the muffin looked at each other. In the third panel the muffin suddenly transformed into a muffin-monster and leered at the frightened looking man. In the fourth panel the muffin, minus the man, rubbed its full stomach, satisfied. I laughed out loud and instructed the three students to go to the copier and make a hundred prints of the comic. Sean’s eyes went wide, “A hundred copies...why?”

“Tomorrow, the first hundred people we see will get a free comic—your comic!” Sean looked really excited. Later after class he approached me and said that he had never seen his art copied a hundred times. He felt incredibly honored. The next day he and the other students distributed the comic to everyone at the convention as they urged attendees to visit our booth.

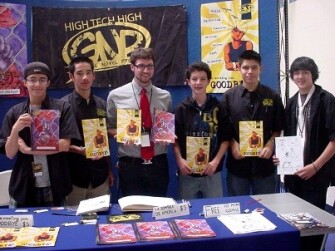

Sean, far right, holding his comic “Muffin-Eats-Man” at the Socal Comic Convention in Oceanside, CA in 2010.

The “Man-Eats-Muffin” comic may not seem like a deeper learning experience, but it was. Through a rapid iteration process, Sean was able to communicate his vision and see how his work had value, not just to himself, but to others too. What I received was a reminder that laughter, silliness, and creativity are accessible to all my students. The most powerful part of the entire experience for me was when I laughed. I hadn’t expected to. In that moment, my pedagogy shifted. It reminded me to get out of the way of my students and to be open to surprises.

Facilitating deeper learning experiences is a risky endeavor. The tenets surrounding the practices of deeper learning are new to educators. How are we supposed to know how to successfully balance a “mastery of core academic content” with “collaboration” or “problem-solving and communication”? We know that the goals of deeper learning are ones our students need, but oftentimes we are afraid to take risks because we are unsure that they (and we) will be successful. We are afraid to fail. But this is a fear we must confront. While it is important to give students access to content, it is equally important to facilitate experiences that connect them to a love of life. This is the heart of deeper learning practices—a pedagogy centered in student engagement, enrichment, and love of learning.

I counseled a lot of our students after Sean’s death to help them process the terrible experience. I would say to my students, “You know, if Sean died one year earlier we never would have known him. He would have never been my student or your classmate. If I had to choose between not knowing Sean and reading about a tragedy that happened to an anonymous high school student, and knowing Sean and having to deal with this pain—I choose knowing Sean.” This idea, the idea of choosing Sean, is my motivation. Not only do I want to make sure that kids like Sean, the ones who are weird and love comics, are lifted up within our system, I also want to ensure that we remember that the lives of our students are happening right now. Death is the one guarantee we have in this existence, but life is something we craft. We need to craft experiences in the classroom that are worthy of our students’ time, because now is the only time we really have.

Photo by Michael D. Hamersky.