I co-authored this post with Sabba Quidwai (@AskMsQ), the director of innovative learning at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California PA program.

In our EdTechTeacher workshops, we often have a similar conversation with teachers—especially at the middle and high school level. Teachers express frustration with digital note taking and organization. In a pre-digital world, their students could theoretically open a notebook and have everything in one place. Now, they seemed to have a collection of files scattered throughout Google Drive as well as paper-based notes. These teachers express a valid concern that their students no longer possessed a centralized home to archive all of their learning. Tony Wagner describes today’s economy as an “innovation economy” where people care more about what you do, than what you know. However, if students are to be successful at solving problems and identifying gaps that present opportunities for design, a strong interdisciplinary foundation of curated knowledge that they can access when needed will serve them well.

In a completely analog, paper-based environment, a three-ring binder proved to be an amazing resource. Notes could get organized into sections and include both printed materials from the teacher as well as personal, hand-written reflections. Students could cordon their knowledge into subject-specific notebooks and easily retrieve it. With this model, students not only consumed content but also curated it.

Fast-forward to today’s hybrid environment. Teachers may post their class resources to a web site or learning management system. Students collect a hodge-podge of media projects, web sites, Google Docs, digital files, and paper notes. Without a system and strategy in place, their learning quickly becomes decentralized and discombobulated. However, when students consciously curate all of their learning into a single place—whether it be Google Drive, Evernote, or OneNote—they can ultimately have a searchable database of their accumulated knowledge that would allow them to see connections not only within individual subjects but across them.

In a webinar this fall, Sabba made an incredibly profound statement. She said that she encouraged her students to tag their reading, research, and notes as a means to incite deeper inquiry. Sabba explains:

In medical education, the content students are presented with is often described as water coming out of a fire hydrant. Such an overwhelming amount of content makes it difficult for a student to take time to synthesize and make connections across the curriculum. We began by asking them to think back to the boxes of textbooks and notebooks that are stored away, too valuable to throw out and yet too inconvenient to access when needed most. As students started graduate school, we asked, "how could you create a space where the valuable information that you will be creating over the next three years could be accessible within seconds?" We found that whether students were using paper, whiteboards, or digital tools to take notes they were working with information in a very linear fashion. This year as our program went 1-to-1 with iPads, we introduced students to apps like Notability, Paper53 and Explain Everything to make their thinking visible and introduced Evernote as a place to synthesize, connect and curate their learning. At the end of each week, month, or module, depending upon how the student wished to organize it, we encouraged them to look across their courses, articles or outside experiences for connections and themes. As they found topics that related to each other, we encouraged them to create tags or keywords that described the relationship. Furthermore, they were encouraged to share these tags during discussions using the visible thinking routine, "What makes you say that?" Justifying their choice and the reasoning behind their choice of tags led to deeper conversations and allowed other students to make contributions, possible additions, and extensions. As students move into their clinical clerkships, this process is encouraged as they will be able to connect real world stories and experiences to content they have learned, encouraging students to create lifelong habits of inquiry and ultimately asking more questions. This process was shared with faculty who were also encouraged to generate tags for their courses. In doing so, conversations about collaboration with other courses came about. These conversations also revealed levels of redundancy of content being presented, which led to looking at how courses can further complement one another to extend learning.

That concept stuck with me as I read, researched, and annotated sources for an annotated bibliography project. First, I tagged articles as I read. This helped me to see broad categories and commonalities as well as to add context to my work. However, these tags added little meaning. As Sabba describes in her process, they were really just keywords rather than reflections.

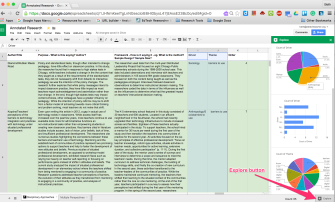

However, I used those tags to identify themes for organizing my sources. As I went back and summarized each article in a Google Spreadsheet, pure magic occurred. By happenstance, something led me to click on the Explore button. At that moment, my tags became quantifiable and trends presented themselves to me.

Sabba’s comment transitioned from being an abstract statement to a concrete set of graphs as I analyzed the various themes in my spreadsheet. In an effort to consolidate the bars on my graph, I looked for commonalities among themes, reorganized my sources, and recognized holes in my research. Through this visualization, my tags led me to ask deeper questions and to consider the resources in a new light.

Often times digital tools for taking and curating notes are seen as a substitution for pen and paper. However, the opportunities to create and synthesize information through multiple modalities allow students to make their thinking visible, self-assess strengths and weaknesses, and connect ideas across the curriculum, placing students in a more poised position to ask deeper questions and construct new knowledge.