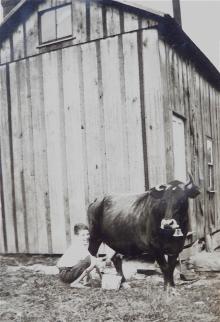

My late father, Fred Cody, (pictured at right, milking the family cow) was born more than 90 years ago in Scott’s Run, West Virginia, a coal hollow in Monongalia County. His mother, a high school graduate, taught school there in a one room schoolhouse. Following his service in World War II, he was able to complete his PhD at the University of London thanks to the GI Bill. He would never have had that chance were it not for the generosity and foresight of the taxpayers.

As a result, I have a great affection for the GI Bill. This law is credited with expanding the middle class in the US, and it certainly helped my family – so the idea of expanding the ranks of those able to attend college is very important to me.

That said, I have been struggling recently to sort out the rhetoric from the reality in the education “reform” movement. According to many of our leaders, all students must be prepared to enroll in a four-year college because all students should attend and graduate college. That will in turn result in the highly educated workforce the US needs for the 21st century.

Many public school reform efforts today are guided by this big idea. In California the Governor has led us to enact a mandate that all 8th graders take Algebra, and many districts across the state are working to match high school graduation requirements to the University of California’s “A to G requirements.”

There is certainly a civil rights issue involved in access to higher education. Students of color, and those raised in poverty have numerous unfair disadvantages, including the quality of their schools. We should do everything we can to strengthen their schools and build the effectiveness of their teachers. We should work to close the achievement gap, and provide opportunities for as many students as possible to attend college.

But is it reasonable to propose that everyone will or should go to college? The reality of our economic straits has begun to cast the shadow of doubt on this vision. I have some basic questions for those who are pushing the system to prepare all students for college.

Currently about 25% of the adults in the US are college graduates. Statistics regarding the economic advantage conferred by a college degree are based on that proportion. What would be the effect on wages of college graduates if that number were to increase substantially? The middle class in the US is shrinking in the current economy, and a college degree in the future may not be as precious as it has been in the past. There do not seem to be enough jobs for the graduates currently emerging from college -- will those jobs expand if the number of college graduates expands? Or will wages simply drop?

We ARE increasing the number of students eligible for college. This week an article in the San Francisco Chronicle reports that the number of students eligible for public universities has expanded by 11 percent – with Latinos showing the largest increase. Now 33% of California’s high school graduates are eligible. But have we addressed the other systemic barriers to them actually successfully completing their studies? The state’s budget mess means the universities will be DECREASING the number of slots available for new students by ten thousand.

As the slots diminish in proportion to applicants, the colleges simply raise the bar for admission – so our schools and students are pursuing a moving – and shrinking – target. And the overall economic picture means that fewer families will have the resources to send their children to college. A recent article in the Wall Street Journal describes the tough choices facing families (including my own) as college tuitions increase, and state subsidies and college endowments shrink. The New York Times reported just ten days ago that:

Among the poorest families — those with incomes in the lowest 20 percent — the net cost of a year at a public university was 55 percent of median income, up from 39 percent in 1999-2000. At community colleges, long seen as a safety net, that cost was 49 percent of the poorest families’ median income last year, up from 40 percent in 1999-2000.

Does it make sense for these students that we are molding their entire K-12 experience around an opportunity that may be an illusion?

This seems like a fraud.

We have a very tricky dilemma. We want our schools to prepare as many students as possible for the most advantageous opportunities, but we also want to prepare them for the actual future they will be facing. It seems to me that our exclusive emphasis on college preparation does a disservice to the many students who will not be on that path. It also points to the trouble with treating K-12 schools as if they are a stand-alone fix for society’s ills. Unless we connect a solid K-12 education to genuine opportunities in our students’ futures, we are not going to accomplish much, and we may actually harm those we are trying to help.

I do not have all the answers here. One of the scary things about the discussion around these issues is that sometimes people behave as if they DO have all the answers, and dismiss the very real qualms being raised. So I end this post with a request for real dialogue.

Should a K-12 education be designed around preparing everyone for college? Should we raise our high school graduation requirements to match the university admission requirements? How will this serve the two thirds of our students who do not go on to college?