This week I have read two points of view about school change that both appeal to me, yet seem mutually exclusive. First I read Sheryl Nussbaum-Beach’s essay, The Fabric of Community- The Key to Transforming Education. She argues that we get stuck reforming our schools, when in fact we should actually be transforming them. Then I read Mary Kennedy’s Education Week commentary, Solutions are the Problem in Education . She describes how the well-intentioned drive to solve problems in our education system is resulting in teachers being deluged with solutions – and becoming exhausted by the resulting constant turmoil. How can we reconcile the desire to improve with the reality that teachers are getting burned out?

Let’s start with a closer look at each perspective. Nussbaum-Beach quotes Phillip Schlecty, who draws the distinction between reform and transformation:

REFORM usually means changing procedures, processes, and technologies with the intent of improving the performance for existing operating systems. The aim is to make existing systems more effective at doing what they have been always been intended to do.

TRANSFORMATION is intended to make it possible to do things that have never been done by the organization undergoing the transformation. It involves metamorphosis: changing from one form to another form entirely. In organizational terms, transformation almost always involves repositioning and reorienting action by putting the organization into a new business or adopting a radically different means of doing the work it has traditionally done. Transformation by necessity includes altering the beliefs, values, and meanings- the culture- in which programs are embedded, as well as changing the current system of rules, roles, and relationships- social structure- so that the innovations needed will be supported.

REFORM in contrast, means only installing innovations that will work within the context of the existing structure and culture of schools.

Nussbaum-Beach relates that in her work, most leaders she encounters are satisfied to be reformers, not willing to take the risks involved in attempting transformation. She concludes:

Personally, I believe that the secret to change lies in developing the social fabric, capacity and connectedness found in communities of practice and learning networks. I believe that by focusing on a strengths-based model of education, looking at possibilities rather than problems, by using inquiry to ask the kinds of questions that reveal the gifts each of us bring to the table, by realizing that "none of us is as good as all of us" and somehow leveraging all of that to shift the conversations toward building a new future- one that focuses on the gifts each teacher, student, parent and leader has, that we have all we need to create an alternative future for schools.

Mary Kennedy, on the other hand, focuses on the often overlooked downside of our drive to improve the schools. She explains that

…we live in a time when reforms and fads have become so commonplace that every new board member or superintendent feels a need to make a personal mark on his or her district by introducing something new. As these policymakers come and go, teachers are buffeted by the raft of competing new ideas they leave behind. So routine turnovers in leadership reignite this continuing series of distractions, further reducing teachers’ chances of finding time for reflection and maintaining a stable environment for intellectual work.

I have experienced this firsthand working in a struggling urban district, which only very recently partly emerged from a seven-year-long state takeover. We have had top-down reform initiatives come and go. Sometimes it seems like the perpetual state of change prevents us from digging in to the real problems at each school site. Instead, we close the school down and start all over, or send the whole staff off to be re-educated.

So what is the answer? I think it is a mistake for administrators to think they can reform schools simply by putting teachers through professional development workshops, no matter how good they are. The transformation that Nussbaum-Beach describes is essential to real school change. Teachers need to develop leadership through being challenged to solve problems, and given some decision-making authority. Teachers need to decide on the process they will follow to develop their inquiry, and implement their solutions. And they need time, and compensation for their efforts. But teachers need to be careful as well, because our students and parents are our partners in this endeavor, and we need to make sure their voices are heard, and their leadership is developed alongside our own.

Thinking about this systemically, the trouble is that teachers and administrators -- let alone parents and students -- are not really expected to undertake this kind of work, and it is very time-consuming. We DO have official mandates to give all sorts of benchmark tests, to align our instruction to standards, and to focus on student outcomes as revealed in the state tests. Administrators are swamped dealing with student discipline, complying with state and district mandates, parent communication, and teacher evaluations. And with current budget shortfalls, administrators and teachers have even more work, as nurses, counselors and librarians are laid off, and class sizes grow. It is difficult to find time for teachers to even meet to accomplish the mandated tasks, let alone the sort of collaboration needed to bring our practices to the next level, or accomplish the sort of transformation envisioned by Schlecty.

So it should not be a shock that the level of stress, and resulting turnover for our teachers and administrators is high. The ones who go beyond mere survival are able to develop sustaining networks of colleagues, to share the work, and provide some mutual support. Wise administrators see that no particular protocol is magic. The key is that teachers have real ownership and leadership in the process, and that they are truly engaged in active reflection on their practices, and working together to improve. That could take the form of Lesson Study, or Action Research, or the National Board’s Take One portfolio process, or any number of other processes and protocols. What matters is that they are actively engaged in an ongoing collaborative process, they are looking closely at student learning, and challenging themselves to improve.

If this sort of transformation is going to be undertaken, we need recognition from policymakers that this is beyond what has traditionally been expected of teachers. We need to recognize teachers as leaders of this work, invest some trust in their ability to tackle this challenge, and compensate them accordingly. Likewise, if we want our parents and students to be involved and developed as leaders, we need to create roles and provide funds to support this work. Without this kind of systemic support, this kind of transformation is likely to be rare and short-lived.

What do you think? Are you a reformer, a transformer or a survivor? How can we sustain educators through this process?

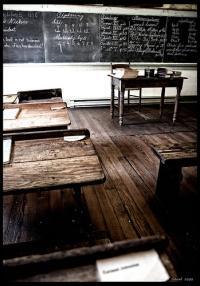

Photo by Rob Shenk, used by permission through Creative Commons.