There is a deep thirst for justice in our schools, and a powerful sense that things are not as they should be. The desire for better outcomes for the less privileged was the original justification for No Child Left Behind, a law that placed the entire responsibility for fixing these problems on the unfortunate staffs who work with these even less fortunate students.

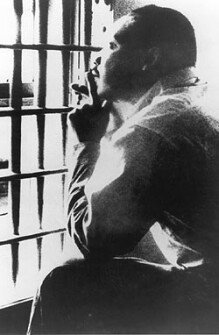

In his speech in Washington, DC, this week, Duncan evokes the ghost of Martin Luther King, Jr., whose Letter from a Birmingham Jail inspired the title of this blog. King was frustrated with religious leaders who counseled patience in the face of intransigent defenders of Jim Crow laws. He demanded action. Here I think we can all agree with Duncan. Something should be done - the question is what.

I started my teaching career studying the words of Martin Luther King, Jr., as they pertained to education. King was a passionate advocate for the poor, and knew very well the deprivations they faced. King advocated desegregation, but much more than that, he was a believer in economic and social justice.

At the conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery march in 1965, King spelled out his vision for the future.

Let us therefore continue our triumphant march (Uh huh) to the realization of the American dream. (Yes, sir) Let us march on segregated housing (Yes, sir) until every ghetto or social and economic depression dissolves, and Negroes and whites live side by side in decent, safe, and sanitary housing. (Yes, sir) Let us march on segregated schools (Let us march, Tell it) until every vestige of segregated and inferior education becomes a thing of the past, and Negroes and whites study side-by-side in the socially-healing context of the classroom.

Let us march on poverty (Let us march) until no American parent has to skip a meal so that their children may eat. (Yes, sir) March on poverty (Let us march) until no starved man walks the streets of our cities and towns (Yes, sir) in search of jobs that do not exist. (Yes, sir) Let us march on poverty (Let us march) until wrinkled stomachs in Mississippi are filled, (That's right) and the idle industries of Appalachia are realized and revitalized, and broken lives in sweltering ghettos are mended and remolded.

In his speech this week, Secretary Duncan described a future for our schools that we can all believe in. He says:

Let's build a law that respects the honored, noble status of educators - who should be valued as skilled professionals rather than mere practitioners and compensated accordingly.

Let us end the culture of blame, self-interest and disrespect that has demeaned the field of education. Instead, let's encourage, recognize, and reward excellence in teaching and be honest with each other about its absence.

Let us build a law that demands real accountability tied to growth and gain in the classroom - rather than utopian goals - a law that encourages educators to work with children at every level - and not just the ones near the middle who can be lifted over the bar of proficiency with minimal effort.

Let us build a law that discourages a narrowing of curriculum and promotes a well-rounded education that draws children into sciences and history, languages and the arts in order to build a society distinguished by both intellectual and economic prowess

.

Let us build a law that brings equity and opportunity to those who are economically disadvantaged, or challenged by disabilities or background - a law that finally responds to King's inspiring call for equality and justice from the Birmingham jail and the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

While these sound like good goals, a closer look reveals that some of them have proven to be mutually exclusive. If you pursue accountability by measuring performance in reading and math, then you get the narrowing of curriculum we have clearly seen in the past seven years. This results in students in impoverished schools having an equally impoverished curriculum - the four hours of scripted reading and math described in the comment here this week by a California teacher.

What is more, there are a few elephants in the room, obscured by this flowery language. According to research by the Civil Rights Project of UCLA, America’s schools are more segregated now than they were in the 1950s.

Latinos and blacks, the two largest minority groups, attend schools more segregated today than during the civil rights movement forty years ago. In Latino and African American populations, two of every five students attend intensely segregated schools. For Latinos this increase in segregation reflects growing residential segregation. For blacks a significant part of the reversal reflects the ending of desegregation plans in public schools throughout the nation.

And these schools, though separate, are definitely NOT equal, as we saw in this blog post last week. The report from the Civil Rights Project states,

Schools in low-income communities remain highly unequal in terms of funding, qualified teachers, and curriculum. The report indicates that schools with high levels of poverty have weaker staffs, fewer high-achieving peers, health and nutrition problems, residential instability, single-parent households, high exposure to crime and gangs, and many other conditions that strongly affect student performance levels. Low-income campuses are more likely to be ignored by college and job market recruiters. The impact of funding cuts in welfare and social programs since the 1990s was partially masked by the economic boom that suddenly ended in the fall of 2008. As a consequence, conditions are likely to get even worse in the immediate future.

Of this re-segregation of our schools we hear not a peep from Secretary Duncan. Only the promise to intensify accountability measures that have resulted in the drill and kill emphasis on reading and math test preparation in the afflicted schools.

Furthermore, even as the schools have become more racially segregated, the gap between rich and poor has widened. The economic crisis has placed even greater pressure on the poor, decreasing school funding, and food and medical programs that serve the poor. It is unconscionable under these circumstances to continue the ritual flogging of schools that has made NCLB such a failure.

President Obama promised a new era of shared responsibility for the school children of our nation. Thus far, however, in spite of the rhetoric, Secretary Duncan’s bottom line holds schools and teachers alone accountable.

What do you think? How can we advance civil rights in the era of NCLB and Duncan?