Tyler Cowen asked doctor and author Atul Gawande what’s missing in medical education. He said doctors needed to learn to work in teams:

“I think the number one thing is an education around the fact that we are no longer a craft. It’s no longer an individual craft of being the smartest, most experienced, and capable individual. It’s a profession that has exceeded the capabilities of any individual to manage the volume of knowledge and skill required. So we are now delivering as groups of people. And knowing how to be an effective group, how to solve problems when your group is not being effective, and to enable that capability—that, I think, is not being taught, it’s not being researched. It is the biggest opportunity to advance human health, and we’re not delivering on it.”

Every profession has crossed the threshold of individual capability--medicine, law, engineering, computer science and education. Most of us work on projects in teams--and those teams are increasingly augmented with smart machines and automated processes.

Seth Godin said two important skills should be central to preparation: how to lead and how to solve interesting problems.

Gawande and Godin suggest that core to preparation is the ability to take on a big problem and break it into component parts, distribute work to a diverse team, work through challenges, and sprint to a public deliverable.

Research Into Good Teams

Google research into effective teams uncovered something unexpected that is key to better teams--group norms. In particular, creating psychologically safe environments stood out. Teams that encourage safe discussions and different viewpoints succeed more.

On good teams, members spoke in roughly the same proportion--what researchers referred to as ”equality in the distribution of conversational turn-taking.” On some teams, everyone spoke during each task; on others, leadership shifted among teammates from assignment to assignment.

The good teams had high social sensitivity. They had team members who could sense how others felt based on their tone of voice, their expressions and other nonverbal cues.

Prepping For Work In Teams

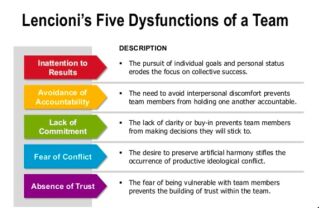

As Dr. Gawande suggests, preparation in every field should include much more about the science of working in teams. That preparation could start with studying what goes wrong. Patrick Lencion’s Five Dysfunctions is a useful summary of what can go wrong.

Work in teams requires a broad sense of awareness and the skills and dispositions of collaboration.

Awareness. Given the inevitability of an augmented future with teams including human and machine intelligence, preparation should start with experiences that promote meta-awareness: self, team, context, quality and tools--that’s social and emotional learning plus strategic awareness and digital literacy.

Given the subtle but important way that smart tools and platforms are curating our view of the world, it’s increasingly important to help young people develop algorithmic awareness. Almost everything they see on a screen was selected by a machine learning algorithm which can be great but also results in a filter bubble.

Collaboration. After awareness, young people should experience success in collaboration including design (design thinking), project management, decision-making, presentation and communication.

Buck Institute editor John Larmer suggests developing clear criteria for teamwork; create a collaboration rubric or another list of expectations/norms and post guidelines on the classroom wall.

Form teams by carefully considering who would work well together. If a particular student needs extra support or understanding (or, shall we say, special handling) put him or her with the right teammates. Team members can write and sign a contract that spells out their agreements about working together, and the steps to be taken when they don’t.

“We constantly talk about collaboration and working in teams with students,” said Randy Hollenkamp, principal at Bulldog Tech in San Jose. Teachers at the New Tech Network affiliate encourage students to create team norms and build contracts with each other prior to every project.

Hollenkamp stresses how trust is crucial to work in teams. “It is as important to students doing the lion’s share of the work as it is to the students not doing the lion’s share,” he said. “If someone in the group is doing more work, then there is a group trust issue that needs to be discussed. This idea is carried into our ‘culture of critique’ as well. The norm here is to be ‘kind, specific and helpful’ when givin a critique. In doing this, our students build trust and seek and expect critiques with each other and adults.”

Conclusion

The nature of work is changing in every profession. New knowledge is being incorporated to attack emerging challenges and solve persistent problems. Teams are developing and delivering solutions with sophisticated tools

Our recent Project-Based World series made the case that managing projects and working in teams should be priority learning outcomes for students, teachers and leaders.

School districts and networks should hold community conversations about how work is changing. These conversations lay the groundwork for updated graduate profiles that name project management, collaboration and social awareness as priority learning outcomes.

As many schools develop an antiseptic version of personalized learning, it’s important to note that project management, social awareness and collaboration arise from extended challenges, not digital worksheets.

After making working in teams a priority, build the infrastructure for success at scale. Schools in the New Tech Network uses a learning platform build for project-based learning. The degree of collaboration and student agency are assessed for each project. These assessments could lead to a sequence of microcredentials and a portfolio of evidence.

It’s time to make project management and skills, and dispositions of awareness and collaboration, priority outcomes.

For more, see: