Academic scholars, as well as educators, have debated the link between students’ enthusiasm for academic work and its connection to learning. If an activity can be made fun, will that help a child pick up new knowledge?

David Geary, a professor of psychological sciences at the University of Missouri, explores this topic in a recent, provocative study in the journal Educational Psychologist. Some of you may be familiar with Geary through his work as a member of the National Mathematics Advisory Panel, but he has an extensive background in cognitive developmental psychology. His study, published late last year, examines what he calls “evolutionary educational psychology,” or the connection between evolution and culture, and the role the schools play in helping students acquire new knowledge.

The process of evolution, Geary says in the study, has resulted in students being able to acquire certain types of new knowledge and skills in a relatively “effortless” manner, through processes that are “child-centered” and fun. These evolutionary processes have helped ease students’ acquisition of language, for instance, and their understanding of living and nonliving things. Children are “motivated to develop social relationships and learn social skills from their peers, because we are a social species and thus biases to learn social skills are built-in and evolved,” Geary explained to me in an e-mail.

Schools have attempted to use child-centered and fun methods, in the belief that students’ natural curiosity will lead them to take on certain, more difficult tasks, like learning to read or do fractions, in the same way they learn language or how to count, he says. But Geary argues that explicit, teacher-directed instruction will be needed for many children to learn more unfamiliar and difficult, or “evolutionarily novel information.” Evolution “has not provided the scaffolding for this learning,” Geary told me. And so “the scaffolding must come from instructional materials and teachers.” Schools should not expect students to be motivated to learn this evolutionarily novel information in the same way they are motivated to learn through social relationships. “There is no such inherent motivation to learn linear algebra or Newtonian physics,” he said. If schools help students understand that effort is necessary and important, children will have a “greater sense of personal control over their learning,” and more sustained focus and motivation as they get older, he writes in the study.

Geary noted that he is not arguing that classroom activities such as strict repetition are always the best way to teach all “evolutionarily novel” knowledge and abilities, only that they will be needed in some cases. Here’s a press release from the University of Missouri that explains some of the study’s main points. Geary fully acknowledges that the study’s conclusions have proved controversial. He’s had a number of researchers challenge his arguments since his paper was published, and he’s responded to them.

Educators—and evolutionary biologists: What do you make of Geary’s arguments?

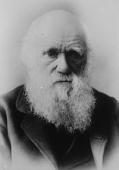

Photo of the godfather of evolution, Charles Darwin, to the right.