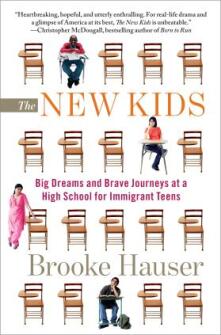

I almost didn’t read Brooke Hauser’s new book, The New Kids: Big Dreams and Brave Journeys at a High School for Immigrant Teens (Free Press, 2011), which was published last fall to critical success. It has actually spent the last six months under my computer monitor, raising the screen to eye level along with a number of other books (placed there by someone else!).

I can’t tell you how glad I am that my editor pointed out the odd placement of the book before finally suggesting that I consider interviewing Hauser.

I recently spent two evenings inhaling The New Kids, and I highly recommend that you run right out and pick up a copy yourself to read. The paperback edition just came out, making it even easier to do so.

In general terms, The New Kids is about the desire and effort of recent immigrants to fit in—both as adolescents and as newcomers—and their efforts to mesh their expectations of America with the reality that confronts them once they arrive and begin their “American” lives. But Hauser, who is 33, has done this by focusing on the stories of specific individuals, bringing to the forefront what those experiences say about education, growing up, being part of a family, and, ultimately, future dreams.

The high school that Hauser focuses on is unusual: Students must have lived in the United States for less than four years and be new English-language learners at the time of intake. All prospective students must take an English-language assessment test to be considered for the school. The only catch, Hauser writes, is that they must fail the test in order to get in. The school itself is home to students from more than 45 countries who speak more than two dozen languages.

— — — —

As I have already said enthusiastically, I really enjoyed reading The New Kids and the light you shed on the education and the immigrant experience. I’m curious: How did this book come to be and how did you select the International High School at Prospect Heights, in Brooklyn, N.Y., as the focal point?

Before I wrote The New Kids, I wrote an article for The New York Times about the same school. For the article, “This Strange Thing Called Prom,” I spent months following a group of seniors as they attempted to plan their first prom, a foreign concept to most of the kids. All of the students at the school are recent immigrants still “learning America” and American high school traditions. They are typical teenagers in most ways—everyone worries about pimples and where to sit at lunch—but some of the students have survived unimaginably difficult journeys to make it to the United States. The prom article only scratched the surface, and after I had finished reporting it, I felt a tug back to the school, which I knew was teeming with amazing stories. I spent the summer working on a book proposal, and in September, with the principal’s permission, I showed up for the first day of school.

I chose to focus on the International High School at Prospect Heights simply because it was close to my apartment at the time. I could walk there if I wanted to, and I often did.

The book dives so deeply into the students’ experiences and lives, which you accomplished by in-person interviews and fly-on-the-wall observations—I’m curious: After a year, was it challenging to remain an observer, rather than a participant in the lives of the students you were following?

At times, yes, it was challenging to stand by and watch a story unravel, as opposed to getting more involved. But sometimes even the act of observing can change a dynamic or a situation. I spent so much time with the students I followed that it was impossible not to become a part of their lives for a short time, but I had boundaries. I tried to refrain from giving advice to students, at least any major advice. For the most part, I let the teachers, administrators, and social workers do their jobs, and I stuck to my job, which was telling the students’ stories. Some of the kids may have seen me as a friend, but I don’t think they ever forgot that I was a reporter. They rarely saw me without a pen and notebook or a tape recorder.

How did you decide which students you would follow in depth? Was it always your intention to focus chapters on specific students’ lives and experiences?

At the beginning of the school year, I asked the 12th grade teachers, “When you go home at night, who are the students you can’t stop thinking about?” One teacher told me about Jessica, a Chinese girl who been kicked out of her father’s apartment during her very first week in America, and who was now living in a rented room in Chinatown. Another teacher told me about Yasmeen, a Yemeni girl whose parents died around the time of her senior year, forcing her to consider marriage when it was her dream to go to college. I found out about other students by reading essays they shared with me. A Tibetan boy named Ngawang wrote his college essay about the time he spent 24 hours trapped inside of a suitcase, being smuggled in the trunk of a car to the border of Nepal. His story is now its own chapter, “Twenty-Four Hours in a Suitcase.”

From the start, I knew I wanted to break out a few “main characters” and focus on individual stories in different chapters. Most of those chapters use the student’s name in the title: “Chit Su’s First Day,” “Dinner for Jessica,” “Capturing Yasmeen,” “The Life and Times of Mohamed Bah.” I wanted readers to remember these kids. I also felt that it worked structurally. The book is set during the school year, and much of it is told chronologically, but I like how everyday high school scenes in Brooklyn are juxtaposed with personal narratives that take us all over the world.

What was the most surprising thing you found out during your year at the school?

Generally speaking, I was surprised to learn how many students were already married or about to get married. Some of the students, girls in particular, were coming from cultures that encourage girls to marry and start families at a young age. As a result, there were a few students who seemed more mature than some of their teachers. In America, we tend to think of teen pregnancy as taboo, but I met a couple of girls from West Africa who were proud mothers as well as capable students. There were many cultural differences that I found challenging and, in some cases, unnerving.

In your mind, what are the book’s most significant take-aways for readers? How about for educators who might work with English-language learner populations without the level of ELL resources available at the International High School?

Education Week‘s Learning the Language blog just published a post about the fact that the population of foreign-born people living in the United States has reached an all-time high at 40 million. There are “new kids” in classroom across the country, not just in Brooklyn, and if we are failing to meet the needs of these students, we are compromising our own country’s future. The New Kids is not a book about politics or policy, but I hope that in reading these personal stories of young immigrants coming of age in America, more people will come to care about a population of students that has been underserved and, in some cases, ignored.

It’s true that the International High School has access to exceptional resources for helping English-language learners, but the most powerful resource of all is a teacher who cares. A few of the educators profiled in this book would go to the ends of the earth to help a student in need, finding a kid a job or a place to live. Others have made a difference in a student’s life simply by staying a couple extra hours after school to tutor or host a special-interest club. They all understand that as new immigrants these students need support in several different areas, not just academics. They also understand that cultural differences can play a huge part in how a student adapts to life in America and at school.

One of the most meaningful letters I’ve received came from an ESL teacher named Megan Andersen in Aurora, Colo. She wrote to say that her students, who usually struggle to read in English, loved The New Kids because they related to the challenges faced by the students in the book. She actually designed an entire curriculum around The New Kids.

The same teacher had her students write their own “immigration stories” for one assignment. What a great idea. From what I’ve seen, encouraging English-language learners to share their unique experiences and cultures through writing not only empowers them, but often inspires them.

A question about the future: It has been almost a year since the book came out, are you still in touch with the students and teachers whom you highlighted in the book? Any plans for a follow-up volume in, say, five or 10 years?

I don’t have plans to write a follow-up. That said, I do keep in touch with many of the students. Some have friended me on Facebook. Most of the kids who I shadowed for the book have kept me in the loop about major developments in their lives. I enjoy hearing updates, but I have chosen not to share them publicly. My agreement with the students was that I would follow them for approximately a year, and I don’t want to infringe on their privacy.

I can say that I’m very excited about this summer. The New Kids was chosen as the summer reading selection for freshmen at the University of Vermont, where currently a handful of International High School graduates are gearing up for their senior year in college. I’ll be heading to Vermont in August for convocation, and I look forward to seeing a few terrific kids, now on the brink of adulthood, who I first got to know back in Brooklyn. It should be a fun reunion.

If you’d like to read more about Brooke Hauser’s thoughts on ELL education, check out my colleague Jaclyn Zubrzycki’s two-part piece in Education Week‘s Learning the Language blog, detailing a conversation she had with Hauser last year. You can find the first post here, and the second post here.