The Norfolk, Va., school district won the Broad Prize in Urban Education last week for its outsized progress in improving achievement, especially among disadvantaged and minority children.

Eli Broad, the founder of the Los Angeles-based philanthropy that has bestowed the award annually since 2002, said Norfolk’s accomplishments derived in part from strong leadership and good relations among the school board, labor unions, and community.

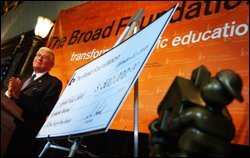

“It is clear that they have made education a priority for all students, and that commitment is evident in their academic results,” Mr. Broad said at the ceremony in Washington where the prize was given on Sept. 20.

The winner receives $500,000 to be used for college scholarships for students. Each of the four finalists—the Aldine, Texas; Boston; New York City; and San Francisco districts this year—receives $125,000 in scholarship money. The Houston; Long Beach, Calif.; and Garden Grove, Calif., districts have won in the past.

In some education circles, Boston was viewed as the favorite to win, since it has been a finalist in all three prior years and Thomas W. Payzant, its superintendent of 10 years, is about to retire. The Norfolk district was a finalist for the last two years, and has been singled out for acclaim by other education groups as well.

Stephen C. Jones, the superintendent in the 36,000-student Norfolk district since July, credited his predecessor, John O. Simpson, who led the district for six years before retiring last year, with leading the work that earned the prize. He said he hoped Norfolk would offer guidance for others.

“This award will really demonstrate that Norfolk was a place that really got its arms around what it needed to do,” Mr. Jones said. “The beauty of these things is not keeping them a close secret, but sharing them so they can help improve instruction for kids across the country.”

The Broad Foundation makes the award after extensive analysis of a district’s practices and achievement data.

Mapping Success

In a Sept. 19 symposium here, leaders of the five finalist districts outlined their strategies for success.

Norfolk officials rely heavily on frequently gathered data to assess how individual children are progressing, how effectively teachers are teaching, and whether the curriculum needs adjustment, said Denise K. Schnitzer, who served as the interim superintendent before Mr. Jones came aboard.

Taking the Virginia Standards of Learning tests as their starting point, district and school leaders forged curricula that included that information, and more. They “backmapped” what students would need to know in each subject by the end of each grade. And they reworked course content “vertically” to ensure that each grade delivers students to the next grade fully prepared. (“One Subject at a Time,” Feb. 2, 2005.)

Schools are encouraged to see themselves as “communities of learners,” where staff members read and discuss books that enrich their philosophy of schooling, and collaborate in grade-level and subject-matter teams to plan their teaching, said Ms. Schnitzer.

The result has been steadily rising test scores, especially among African-American students, who make up two-thirds of the student population.

Only 40 percent of black 5th graders, for instance, met state standards in reading in 1997-98, but by 2004-05, that figure had risen to 77 percent. Among white 5th graders, 90 percent met the standard last school year, compared with 67 percent eight years earlier.

The performance gap between black and white students has shrunk from 27 percentage points to 13.