Americans of every state and stripe are having fewer children, reports the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yet a new international study suggests the trend may provide a counterweight to the country’s stubbornly high poverty rate if the United States also makes sure that the children we do have are better educated than the generations that came before.

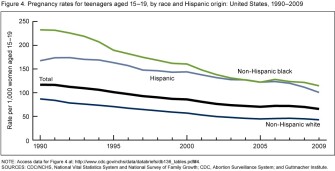

According to a new CDC report on birth rates, U.S. pregnancies and births are at a 12-year low, and for married and unmarried women alike, the pregnancy rate dropped 10 percent from 1990 to 2009. Moreover, the rate of teenage pregnancy is also at a 20-year low: It fell from 77 to 37 for every 1,000 women ages 15-17 and from 168 to 107 per 1,000 women ages 18 and 19. CDC researchers suggested the “steep declines” in births to teen parents could be coming from a long-term reduction in the numbers of sexually active teenagers and a simultaneous increase in the percentage of teenagers using contraception from the first time they have sex. In fact, CDC researchers found across the board, more women shifted to starting families after age 30 and having fewer children.

How is that likely to affect American progress? A separate, international study of more than 100 countries suggests it may depend on how well we educate the children who are being born. The study, published in the current issue of the journal Demography, finds that economic gains in other countries which had been credited simply to lower birth rates actually came from improving education levels.

Prior studies found that as a country’s birth rate drops, it often revs up into a period of rapid economic growth, commonly called the “demographic gift.” For example, studies in the 1990s showed that smaller family sizes explained a large chunk of the rapid growth of East Asian countries during that time.

Researchers at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital in Vienna, Austria, looked at economic and demographic changes in 105 countries, including the United States. They then controlled for more subtle changes, such as shifts in the size and age of the working population, overall educational attainment, and the change in education over time.

In the end, it wasn’t enough for countries to lower their family size. Countries which had fewer children but rising overall education levels had faster and better economic growth than countries that did not increase their peoples’ overall educational attainment as birth rates fell. Wolfgang Lutz, a study co-author and Wittgenstein Center director, said the results “demonstrate the decisive role of investments in universal education in bringing countries out of poverty.”

That’s something to think about, considering that the bulk of the American South, Southwest and West Coast now have a majority of their public schoolchildren in poverty.