Washington, D.C.

When it comes to helping teachers and education leaders use research, U.S. advocates may have something to learn from how their colleagues across the pond connect research to practice.

The Society for Research in Educational Effectiveness’ annual conference here last week highlighted new ways the United States is learning from the United Kingdom both in research development and the use of research in the field. Attendees heard about British practices on everything from protecting student privacy in linked governmental data to helping district leaders find evidence for better school improvement to building a pool of districts interested in working with researchers.

The discussion comes as states and districts work to implement evidence requirements in the Every Student Succeeds Act, and as Congress debates the future of research in public policy.

In fact, lawmakers have already started moving to adopt one British innovation for giving researchers secure access to linked government data: the National Secure Data Service. The service—one of the innovations proposed in the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act, which has passed the House and is working its way through the Senate—is modeled on the UK Data Service.

The British data service creates temporary, privacy-secured datasets linking from some 6,000 national datasets in areas from basic demographics to employment, education, and healthcare. The service helps researchers run secure data studies without creating a central data warehouse, which privacy watchers in both the United States and Britain long have opposed because of the risk of students’ private data becoming identifiable.

“If we can get the data service, we would get the use of all those data systems without the downsides” to privacy and spending of a central repository, said Ron Haskins, former co-chair of the Congressionally appointed Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, whose report is the basis of the bill, and co-chair of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Evidence-Based Policymaking Initiative.

But U.S. education researchers also think the policymakers could take a page from the British playbook on how to help school leaders and practitioners make better use of research to improve schools.

“A lot of the advantage in linking these massive data systems is to be able to monitor change over time and develop hypotheses that could be tested over time,” said Adam Gamoran, the president of the William T. Grant Foundation, in a symposium on the future of the commission. “Not just to test program impact, but to develop policies. ... And for that, we need to build capacity for building and using evidence in the federal government.”

Making Research Easier to Use

“Whether our work is closely connected with policy and practice is an existential issue,” said Ruth Curran Neild, in a keynote speech at the Society for Research on Education Effectiveness conference here. “In the long term, the field cannot expect to continue to receive support for its work ... unless there is credible evidence that findings from carefully designed and executed research regularly inform and influence education practice and policy to good effect.”

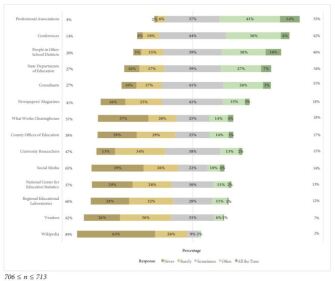

For example, Neild, the director of the Philadelphia Education Research Consortium and a former acting director of the federal Institute of Education Sciences, pointed to a 2016 study, which suggested district and school leaders look to professional groups more than university or governmental groups to find evidence for making decisions. Fewer than 1 in 5 of them frequently used the federal What Works Clearinghouse or regional laboratories for help in finding research.

By contrast, Neild later pointed to the UK-based Teaching and Learning Toolkit—which categorizes the evidence supporting interventions in 13 different areas, from school organization and parent involvement to literacy strategies and student behavior. More than 65 percent of school leaders in the country report using it to find evidence for school improvement strategies. The tool, supported by the government but operated by the nonprofit Education Endowment Foundation, includes ratings on the average costs and quality of the research on the topic, and lists the average effects translated into months of additional learning:

The site focuses on studies with at least 100 schools, and more than 90 percent of the studies are randomized controlled trials. The overall page uses only average effects to estimate the effectiveness of interventions, but school leaders can click on different interventions to get more information about their effects in local contexts or specific student groups.

For every school in England, the foundation has created a set of 49 schools matched on student demographics, resources, geographic context and other factors, that allow school administrators to compare their own practices and results against similar schools.

“At some point when using evidence, you have to ask the question, is it working here?” said Kevan Collins, the chief executive of the foundation. As part of the site, school leaders who are interested in testing out interventions can sign their sites up for active or forthcoming studies, creating a pool of available schools for researchers, as well as a network of practitioners with similar interests.

The group now is developing a database of 15,000 studies on teaching and learning topics from around the world. “The evidence on phonics is just as interesting if you are trying to teach English in New Delhi as if you are a teacher in Lancashire in England,” Collins said.

Chart: A 2016 report from the National Center for Research in Policy and Practice finds school and district leaders are most likely to turn to other practitioners to find research. Source: “Findings from a National Study on Research Use Among School and District Leaders”