It happened so quickly. Last year, I Am a Pencil, my memoir about teaching creative writing to immigrant kids in New York City, was published. Within weeks, a publisher in Japan had purchased the rights, and six months later, the Japanese translation was nearly complete. The publisher had such high hopes for the book that he did something rare: He invited me to Tokyo, all expenses paid, to promote it. I accepted with pleasure but scratched my head: Why was Japan so excited about my book?

I got my first inkling in an e-mail that arrived several months before my trip:

Dear Mr. Swope:

I AM A PENCIL is just a Wonder-ful book. I enjoyed it so much and I wish to thank you for having written such a splendid story. (Of course I know it’s a memoir, a non-fiction, but I often felt as if I was reading a fairy tale! MR. SWOPE AND 28 IMMIGRANT FAIRIES!) Every episode is touching, often funny, and hilarious. ... I really appreciate if you would kindly reply to this e-mail. I have something more to talk to you!

Would-be best friend of yours,

Kim (59, Korean male born in Japan)

This communication raised a couple of questions. Why was a 59-year-old Korean reading a book about kids in the United States? And why did he want to be my best friend? I replied briefly to offer my thanks, and the next morning this confession appeared in my inbox:

I have to tell you something I should have written in my last letter. As a matter of fact, I am the translator of your book. Please don’t be offended at my withholding this fact. I just wished to write to you first as a reader and a friend.

My translator had chosen an odd way to introduce himself, but I wasn’t offended because he’d taken my book’s characters, both students and teachers, so much to heart. He’d even asked after my cat, Mike, who appears in the book, and when I told him Mike had died, he replied:

I am so sorry about Mike, and I believe she lived her life as the happiest cat in New York! Every morning I do a ceremony and burn a stick of incense for my parents, who came to Japan from Korea 70 years ago, and both passed away when I was only a kid. So tomorrow I will burn an additional one for Mike.

| |

| (Requires Macromedia Flash Player.) |

And so began my friendship with I-kwang Kim, whose moving life story I’d learn in bits and pieces, first through e-mail and later in person. Nothing he’d tell me, however, shocked me more than this: Although born in Japan to Korean parents, Kim wasn’t a citizen of either country. Japan denied him citizenship because his parents were Korean, and Korea, for reasons of its own, didn’t claim him, either. With only permanent resident status in Japan, Kim can’t vote and is legally barred from certain professions. Given such state-sanctioned discrimination, it’s not surprising there’s anti-Korean sentiment throughout Japan, a circumstance which further limited Kim’s opportunities and broke his heart many times.

Of course, not all Japanese are bigots. Kim’s wife is Japanese, as are many of his friends. What’s more, he’s found much to love in Japanese culture, including the language, which is his mother tongue, and he enthusiastically urged me to see many wonderful sights: Mount Fuji! Kamakura! Kyoto!

He seemed puzzled, however, when I mentioned I wanted to visit Hiroshima and donate my services by giving a workshop at a school. “Why do you want to visit a Japanese school, especially in Hiroshima?” he wrote.

The answer had to do with complicated feelings about my country’s use of the bomb. The mushroom clouds that obliterated Hiroshima and Nagasaki cast a shadow each time I ducked and covered during school air raid drills in the 1960s. Ever since, I’ve lived with a nagging background dread of apocalypse. Of course, I understand my country’s rationale for dropping the bomb—that it ultimately saved lives, both Japanese and American, by ending the brutal war Japan had started. Nevertheless, in targeting a civilian population with nuclear weapons, a line had been crossed, a precedent set, and from that moment, the world has hung by a thread. I wrote to Kim:

I’m not sure why it is that Hiroshima is calling me. ... Perhaps it’s a sort of pilgrimage. I want to understand what happened better. As for why I want to visit a school, that’s even harder to ex plain, but I suppose it’s a tiny gesture I want to make, a small token of good will, perhaps even a penance. I’m not exactly sure.

Kim, eager to help, made some calls and found a high school pleased to have me visit. Then he asked if he could come along. “You see,” he wrote, “I was born in Hiroshima three months before the atomic bomb exploded. I was there only one short year and never have been there since. ... So it could be a wonderful sentimental journey to me.”

Kim didn’t elaborate on this extraordinary revelation, but it wasn’t hard to imagine his infancy. I’d been reading Barefoot Gen, a graphic novel by Keiji Nakazawa that shares with Art Spiegelman’s Maus an uncanny, searing power. Set in Hiroshima in 1945, it tells the story of a boy named Gen, whose artist father is passionately against his country’s war, a position that makes the family pariahs. When the bomb explodes, Gen and his pregnant mother are the only two in his family to survive. The trauma induces labor, Gen’s mother gives birth surrounded by the flames of the destroyed city, and the boy is sent into the horrors of Hiroshima to search for food and water.

I told Kim I’d welcome his company, and he promptly made arrangements, booking trains and hotels. When I boarded a plane for Tokyo in June, everything was set.

Kim met me at the airport. He was short and lithe, with a thick head of hair, and looked closer to 45 than 60. Both of us were nervous, as if on a blind date, and because each was eager to honor the other’s customs, our greeting was a farcical confusion of bows and attempted handshakes.

“Finally, we meet!” he said with his elfin laugh, both sad and merry, a laugh I’d hear often in the coming days.

!["I immediately felt at home in Tokyo," Swope writes. "It had New York [City]'s energy and craziness and sophistication" — with one difference. The American city is much more multicultural.](https://epe.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/570a464/2147483647/strip/true/crop/300x225+0+0/resize/300x225!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fepe-brightspot.s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com%2F53%2Fff%2Fc310d1fd764b3ba8beda3ec93510%2F3japan2.jpg)

Also there to greet me was Shin-ichi Yamaura, my Japanese publisher, who was a handsome, genial man in his 40s.

“Very pleasure to meet you, Swope-san,” he said, using the Japanese honorific granted to both males and females.

Although all Japanese study English for six years, they get little practice speaking it. Because of phonetic differences in our languages, it’s hard for native Japanese speakers to distinguish between English r’s and l’s, and Yamaura almost always mixed them up, turning “clouds” into “crowds,” “rice” into “lice.” At the same time, he was a wonderfully animated speaker and made liberal use of Japanese exclamations like “Honhhh?” and “Mghmghmghmgh”—which aren’t precisely words, but are enviably expressive.

On the train into Tokyo, Yamaura gave me a gift, a handsome Japanese paperback, and it took me a moment to realize this book I couldn’t read was written by me. Yamaura pointed to the title and confessed he’d changed it to The Pencil Is a Magic Wand.

This was within his contractual rights, so all I could do was smile and nod. Given the change, though, I wondered why the English words “I Am a Pencil” were also on the cover.

“In Japan, English language cool,” Yamaura explained. “English word make very good sale!”

The Japanese, I’d discover, often use English as an element of design, but because no one cares what the English actually says, designers don’t bother to get the words right. That’s why I’d see so many T-shirts emblazoned with puzzlers like “It is a success to the person with the same heart!”

I asked Yamaura why he’d published my book.

“Pencil book very sensoorahity. You are very sensoorahity.”

I couldn’t be hearing right. I asked Kim, “Is he saying sensuality?”

Kim wasn’t sure. After conferring in Japanese with Yamaura, he said, “Yamaura-san means your book has much sincerity.”

“Yah,” said Yamaura. “Seen-cer-lah-ty! Very much sales Japan. Yah. I think so.”

Upon arriving in Tokyo, Yamaura, a bon vivant and a generous fellow, invited us to dinner. What would I like? Italian? French? American?

“How about Japanese?”

Yamaura was shocked. “Really? You like Japanese food? You like sushi?”

“Very much.”

“Ah, so!” he cried, delighted. But he took us to a Chinese restaurant, anyway.

I immediately felt at home in Tokyo. It had New York’s energy and craziness and sophistication. There were skyscrapers, subways, lots of cabs, plenty of shopping, and crowds on the street dressed in everything from Ralph Lauren to grunge, just like in New York—except for one startling difference. In New York, the faces come from all over the world. In Tokyo, they are overwhelmingly Japanese. I felt I’d entered a Twilight Zone version of the city I call home.

Unfortunately, I didn’t see much of Tokyo because I was held prisoner in my hotel suite: day after day, interview after interview, the same questions over and over again. It was heady, in a way, having so many people eager for my opinion, but before long I was sick of my own voice.

Sometimes, though, the questions gave a glimpse into Japanese education. Several journalists were fascinated by the idea of teaching creative writing because it’s not a subject taught much in their country. One was surprised I wrote that I’d fallen in love with my class. “Japanese teachers aren’t so involved,” he said. Another explained that Japan’s economic slump had prompted debate about whether schools should encourage creativity to build a more innovative work force. And many mentioned a rise in violent incidents in Japanese schools, leading some to wonder whether creative expression could help the situation.

My biggest media moment would be an appearance on a television program so popular that Bruce Willis had been a guest. Yamaura translated its title as Everyone Must Speak English Tonight! but I never got a clear idea of the show’s format. All I knew was that I’d be in a segment featuring a teenage model who had written a journal in English.

Earlier in the week, the show’s producers had dropped by to give me samples of her writing. This was a typical (and complete) entry:

Which my hair do you think better? It’s looks grow side hair. And It’s looks child front hair. I don’t know which I do. That’s because I take a CM audition.

“You put this on the air just like this?” I asked.

The producers nodded proudly.

“But it’s full of mistakes!” I cried. “It makes no sense!”

My shock delighted the producers. They were all smiles. “You be harsh with her!” they said. “Berate her!”

“Does she speak English?”

“Not really.”

“How can I teach if she won’t understand?”

“No problem. We fix everything in editing. You talk to model, but audience learn, too. Model represent audience. You teach audience, through model. No problem.”

I smelled fiasco, but what was I to do? Yamaura had said, “TV show very important sales for Pencil book!”

The show was taped in a vast studio, but the set was small, just a blackboard and a table at which sat the teenage model, with toothpick arms and foot-long earrings, worrying over her nails. I was hoping we’d do a run-through first, but suddenly—

“Lights! Camera! Action!”

Immediately the model and I were all smiles.

“Hello!” I said. “How are you today?”

“Hello!” she mimicked. “How are you today?”

“Good, thanks. And how are you?”

“And how are you?”

“No: How are you?”

“How are you?”

This was going to be worse than I’d thought. I leafed through her journal and said, “Your writing would be better if it were more specific.”

“Espesfik?”

“Spuh-sif-fik.”

“Spukicifikik!”

“You need to use more details.”

“Details?”

“Because details help a writer paint a picture with words.”

“Enh?”

The poor girl wasn’t understanding, but I’d taken the producers at their word and was talking through her to the audience. “Good writing is tactile,” I continued. “We want to see, smell, hear, touch, and taste your sentences.”

“Taste sentence?”

“But you don’t just want a list of details. That would be boring. You must tell an interesting story.”

“Tell story?”

“What’s an interesting thing that happened to you recently?”

“Enh?”

I spoke slowly: “What ... do ... you ... want ... to ... write ... today?”

“Today? Write?”

“Yes. Are ... you ... ready ... to ... write?”

“I ready. I was join my crub fakal yesterday. So I didn’t bring sport.”

“Enh?”

“I tie clab lestahlant. I was all-you-can-eat!”

It took forever to get a few comprehensible sentences out of her, and by that time, both the model and I were exhausted, but the producers seemed satisfied.

“Sank you,” they said, bowing. “Sank you a rot.”

The next morning, Kim and I boarded a bullet train and whooshed across Japan. We stopped in Kyoto for the afternoon to see gardens and temples and to visit Kim’s haunts from the 1960s, when he was a student at Kyoto University, Japan’s equivalent to Yale. Given Kim’s living situation back then, it’s amazing he passed the entrance exams. After being orphaned at age 12, Kim was taken in by relatives who eked out a living making rubber gaskets on an appalling machine that sat in their tiny home, filling it with clatter, dust, and the stink of rubber. When Kim wasn’t pressing gaskets, others were, making it difficult to sleep or study. But thanks to brains and perseverance, he aced the notoriously difficult exams, got a scholarship, and earned a degree in English literature.

We found the residential street where he’d lived, but his building was gone. The home next to it still stood, however, and Kim stared at it, then made a sound that seemed a cross between a sigh and a moan. He told me he’d tutored a young woman there. Each time he came to teach, she’d have a meal prepared. Kim said, “She loved me so much!” In those days, Kim lived a lie, hiding his Korean identity by using a Japanese name. When the young woman somehow discovered his secret, she immediately cut him off, and Kim was no longer welcome in her home.

I asked Kim if he, or anyone, could tell by sight whether an individual is Japanese, Korean, or Chinese. “No,” he said. “In most cases, you can’t tell at all.”

This is bigotry at its most abstract. It isn’t based on anything you can see, like gender or skin color. And it isn’t based on beliefs or behaviors, like religion, politics, sexuality, or disability. How strange—to love someone and then not, simply because they’re of Korean stock, the same stock that, evidence suggests, migrated from the Korean peninsula and settled in Japan in the third century B.C., bringing the agricultural and metalworking skills that would transform the island’s Stone Age culture.

We arrived in Hiroshima that night, and by the time we checked into our hotel, it was after 10. Kim went to bed, and I went for a walk. Our hotel was downtown, surrounded by office buildings, department stores, restaurants, and boulevards. It was jarring to experience Hiroshima as a thriving and completely reconstructed city. If I hadn’t known where I was, I never would have guessed. As I wandered, inevitably my mind dwelled on death, which may explain why my cat Mike entered my thoughts, giving me a twinge of grief. This was soon displaced, however, by the sight of a baseball stadium, so incongruously American that I did a double take. I shouldn’t have been surprised, of course. The Japanese are crazy for the game, and Hiroshima, I’d learn, fields a pretty good team.

Then I heard a meow.

Across from the stadium was a park, and sitting on a pathway was a cat. I crouched and held out my hand. She didn’t come, so I took a step forward. She darted down the path, then stopped to see what I’d do next. Again I approached. Again she ran. Like a creature in a fairy tale, she led me into the park until we came to the gutted remains of a brick-and-stone building, a former exhibition hall, one of the few structures left standing on August 6, 1945. This ruin, now a memorial, once had a domed roof, as on a church. It was beautifully lit, and the setting was romantic, with lovers strolling arm in arm and the Ota River flowing nearby and reflecting the moon.

I tried to imagine that morning 60 years ago. The weather, I had read, was fine, the sky deep blue. Shops were open. Horses drew carts along the streets. Teachers were in their classrooms, clerks at their desks. At 8:15, they all heard a massive explosion, which was immediately followed by a white sheet of light. The heat was so ferocious that the eyes of anyone gazing at the sky melted. Clothes turned to ashes, and survivors stumbled to the river, skin dripping from their bodies like wax. Perhaps as many as 100,000 people died instantly, and tens of thousands more suffered lingering, unbearable deaths, including Sadako Sasaki, who died of leukemia 10 years later at the age of 12—but not before she’d folded the thousand paper cranes that became an international symbol of peace.

Where do history and blame begin?

In the 17th century, Japan’s ruling shogun expelled all foreigners and locked the island’s doors. For more than 200 years, no outsiders were allowed in and no Japanese were allowed out. Remarkably, throughout this long period of isolation, Japan was at peace. Commerce and art flourished. Warriors, with nothing else to do, became bureaucrats.

As the 19th century reached its midpoint, clouds appeared on the horizon. The United States, responding to the economic imperatives of capitalism, went in search of new markets, and in 1853, Yankee warships entered Tokyo’s harbor, forcing Japan to do business. Our history books call this “the opening of Japan,” but what we really opened was a Pandora’s box.

Compelled to play the Westerners’ game, the Japanese abandoned feudalism, became capitalists, and rapidly built an army that astonished the world, one strong enough to defeat its Russian and Chinese counterparts and support a brutal empire whose colonies would include Taiwan, Manchuria, and Korea, which Japan annexed in 1910, shortly before Kim’s mother and father were born.

In the latter ’30s, Japan began expatriating Koreans and other colonists to slave for its war machine and die on the front lines, but Kim’s parents emigrated as economic refugees desperate for work. Life in Japan proved hard for them, though, and both died young, never seeing their homeland again. (Korea remained a colony until Japan surrendered in 1945.)

By the time Kim set eyes on Korea, he was in his 40s and it was a divided country. Of his first journey to his parents’ home in present-day South Korea, Kim told me, “When the ship was crossing over the straits which my parents crossed in the reverse direction [more than 50] years before, I cried and cried, which I couldn’t stop.”

In the morning, Kim and I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which is impressive and harrowing. In describing the events that led to the bombing, the various exhibits acknowledge Japan’s aggression and describe the debate over our use of the bomb, then let the subsequent devastation speak for itself. Kim was heartened to see so many school groups there, but he lamented that in Tokyo, students had little knowledge of the war or of the bombing. I said few American students knew that history, either.

On this disheartening note, we arrived at Motomachi Senior High School, where an American flag had been raised in my honor. Waiting outside was a smiling delegation led by principal Yoji Matsumoto. After we all finished bowing, we entered a vestibule, removed our shoes, and put on slippers that, as always in Japan, were too small for my American feet.

Motomachi High, just a few years old, is officially, and movingly, devoted to the study of peace and art. It’s a stunning building, all steel and concrete and glass. The design is both elegant and severe—what a prison by Armani might look like. As Matsumoto showed us around, he was particularly proud of the sun-filled studios for painting, sculpture, pottery, calligraphy, architecture, and computer design. Classes were in session, so the long, broad corridors were empty, and when we rounded a final corner, I was startled by a confusion of television cameras and photographers and the sound of cheering children.

It took a moment to realize this fuss was for me, but there was no stopping things. At once mortified and flattered, I was rushed under an archway festooned with flowers, swept along a line of applauding teenagers, and delivered into a classroom set up for a round-table discussion with 16 students, most of whom wanted to be artists. They were charmingly shy at first, and after a few silly questions—my favorite movie? favorite food?—a girl with a pixie haircut raised her hand.

“Please, Mr. Swope. How writing can contribute to peace?”

“It’s risky to write with the intent to give a message,” I said, repeating advice I’d given many students who’d turned in sappy stories about universal love. “The message must grow from the narrative. Because without a good story, your message has no power. Does that make sense?”

The children looked at me intently, but no one responded. Perhaps they hadn’t understood. Or had I said something wrong? Was my answer too negative? I scanned the room. It was impossible to tell. To fill the silence, I asked, “What’s it like to grow up in Hiroshima?”

The girl with the pixie haircut said, “I feel is privilege born in Hiroshima. Children here are always doing lesson about peace. When I went first time to Peace Museum, I couldn’t believe my eyes because it was very terrible and I cried. So born in Hiroshima very great fortune because it is my wish to spread all over the world what I learn here.”

Such idealism, coming from a child in Hiroshima, was chastening. I was still reeling from the selflessness of this response when another girl asked, “Please, Swope-sensei. How can we teach children peace?”

Swope-sensei! “Respected teacher”! But what could I tell her? I had no answer to this question and I couldn’t make one up—not here, not with these kids, not in Hiroshima.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I don’t know. Perhaps you can tell me?”

“I think,” she said, struggling for the English words, “we can teach children peace by teach them about war.”

Her answer left me speechless. But she was right, of course, and had offered up the great lesson of Hiroshima, the mission its survivors took on in the wake of their disaster: to advance the cause of peace by testifying to the catastrophe of war. They would not let the world forget.

I expected to leave Hiroshima depressed. Instead, I was inspired. Kim was, too. But when I asked him how it had felt on a personal level to return to his birthplace, Kim said he’d felt nothing. And, on reflection, how could it have been otherwise? He’d been so young at the time, less than a year old. Inevitably Hiroshima became an abstraction, a place he couldn’t remember and one his parents never discussed—perhaps because they’d died before Kim was old enough to be told what terrors they’d been through.

Our trip had, however, led Kim to the “awakening,” as he called it, that his life hadn’t truly begun in Hiroshima. “When I was young,” he explained, “I kept asking myself: Why am I not a Japanese? Why must I hide my identity? Why can’t I have their same jobs, hopes, dreams?” The answer, he now knew, was that his life journey had started before he was born—in Korea. But if this understanding brought Kim peace, it also condemned him to wonder what might have been, which in turn explained why he’d wept so fiercely on the ship that took him to Korea.

As with all children of immigrants, Kim is caught between the culture his parents left and the one in which he grew up. “I like Japan, and I will always live in Japan,” he said. But it was clear he’d do so at a remove, unable to fully embrace the country that never fully welcomed him.

Bit by bit, Kim told me, discriminatory laws in Japan were being repealed. Yet despite the fact that he could now become a naturalized citizen, Kim chooses not to. When I asked why, he didn’t mention the indignity of having to apply for citizenship to the country of his birth, the country whose policies had forced his parents’ immigration and stunted their lives. He merely said, “Pride to my roots.”

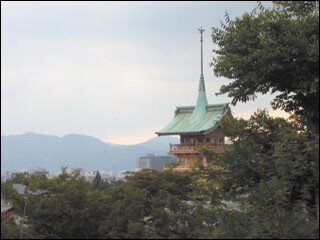

As a coda to our trip, Kim took me to Koyasan, one of Japan’s most sacred places, a mountaintop where bald Buddhist monks tend to more than 100 temples, the first of which was founded in the ninth century. Kim made reservations for us in one of them and gave me the nicer room. It was spare and elegant, classically Japanese, with murals on the walls, tatami mats for a floor, and the only furniture a low square table and a few cushions.

A shoji screen opened onto a private garden, where a waterfall tumbled from the mountain forest into a pond full of carp and surrounded by grass, azaleas, rhododendrons, and delicate maples. The Japanese have a genius for gardens, and perhaps this has something to do with their ancient belief that gods inhabit every tree, every stone, every flower. Whatever the explanation, they are mysterious, enchanted, spiritual places, and immensely calming.

At prayer time, I heard monks chanting in the distance.

In 1945, it was said that no plants would grow in Hiroshima for 75 years. Yet the following spring a tree, burned black by the bomb, began to bud, and devastated survivors gained strength from the emergent green. Sixty years later, I, too, had taken heart. For the first time in my life, I could imagine a world without the bomb. Peace wouldn’t come easily, of course, and might require another cataclysm, a destruction worse than any seen before. But it seemed at least plausible that out of the ashes could come a charismatic leader, a Gandhi, a Martin Luther King Jr., a warrior of peace who perhaps once had worn a pixie haircut when schooled in the lessons of war at a place like Motomachi High.