Too often, when I look around at what passes for innovative practices or cutting-edge policy recommendations, I see something very different: I see us perfecting our ability to succeed in a system that no longer serves our interests.

Two recent articles reinforce this point -- and light a different path, one that will actually help us reimagine education for a changing world.

The first highlights the thinking of John Abbott, the head of the 21st Century Learning Initiative. Some of what Abbott says, like the need to replace the Industrial-era model of schooling with something more personalized, has been said by lots of people, in lots of places. But other insights frame the challenge in ways I found to be both new and helpful -- such as the notion that a child’s path through school should be based on the biological system of weaning -- i.e., gradually reducing children’s dependence on teachers. “Teacher-student ratios should be high in the early years,” Abbott contends, “then decrease dramatically in adolescence, when the whole community has to become a place of learning, with mentorships, apprenticeships and other hands-on learning experiences complementing highly self-directed classroom learning.

“Children learn most from what they see going on around them,” he explains. “We become who we are based on things around us that we admire or not. Children don’t just turn their brains on when they go to school.”

The challenge, then, is how to operationalize the sort of blueprint for a 21st century learning model that Abbott describes. And the second article profiles the school that, for my money, is doing this better than anyone else: the MC2 school in Keene, New Hampshire.

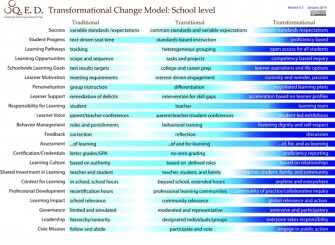

Founded by Kim Carter, who also leads the QED Foundation, an organization that has mapped the past, present and future of teaching and learning with prescient clarity (see for yourself below), MC2 is the rarest of places -- a public school that is consistently and holistically designed to reflect the latest research on adolescent development, motivation, and learning sciences.

In fact, its design mirrors the recommendations of Abbott by way of its description of the learning process as a J Curve, or a rapidly accelerating path to self-direction and engagement, based on heavier investments in adult mentoring and support at the earliest stages of the learning process.

What would the next phase of school reform efforts look like if greater attention was paid to the insights of experts like Abbott and Carter?

That’s a question I’d like to see us answer.

Follow Sam on Facebook.