Guest post by Andrew Ujifusa

One of the words frequently associated with rural education is “challenges.” It’s one that U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan used last year to describe what faces many such districts, which are educating a poorer and more diverse set of students than they used to. So how can policymakers and others help to create rural schools that thrive?

That’s the main question addressed in “Uncovering the Productivity Promise of Rural Education,” a set of four essays in the latest volume of the State Education Agency of the Future edited by Betheny Gross and Ashley Jochim. Specifically, the four writers address what state education agencies can do to provide more support for rural schools on issues ranging from technology to giving them breathing room on keeping up with regulations.

‘An Attribute of People’

The title of the first essay by Paul Hill, of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, is blunt: “States Could Do More for Rural Education.” In addition to highlighting the leadership challenges and the number of high-achieving students who get overlooked in such districts, Hill encourages readers to move beyond demographic descriptions of rural schools.

“But rurality is more than simply an attribute of place. It is an attribute of people who do certain kinds of work (e.g., farming) or have certain relationships to land and community. It is also a set of attitudes about tradition, close-knit community, a relaxed pace, and a preference for recreation in wild and unpopulated areas. These ways of being rural are not perfectly associated with the hard, data-based distinctions used by the Census, the Office of Management and Budget, or [the National Center for Education Statistics].”

As far as solutions, Hill advises funding flexibility as well as greater incentives for rural districts to share resources and strategies.

But he also advises that rural districts may need to approach politics differently than some of their peers: “A distant or legalistic relationship might work for big urban districts, with their own dedicated lobbyists, lawyers, and elected officials. But rural leaders need the kind of leadership that they themselves provide: personal, case-specific, and focused on solutions, not rules.”

Outliers

In her essay “Promoting Productivity: Lessons from Rural Schools,” Marguerite Roza of Georgetown University challenges some of the conventional wisdom about rural schools and their performance. She acknowledges that rural schools on average have a relatively low “return on investment,” or ROI, when their academic performance is measured against their financial support from states.

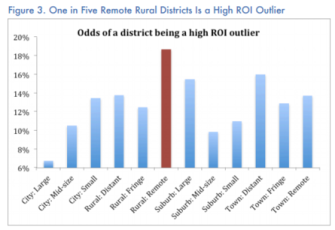

However, Roza points out the odds of a rural district being an outlier and providing high ROI is actually quite good, nearly 1 in 5, compared to other types of districts, as her chart below shows:

She says that thinking about rural schools in terms of their deficits might not be a reliable approach:

“We might consider how isolation and smallness could foster conditions that increase the chances of education innovation, seeing these rural factors as opportunities instead of only deficits. Where districts don’t have the need or capacity to implement large operational systems, perhaps they are better able to capitalize on the strength of specific staff or community.”

Here are a few of her recommendations for state education departments to consider:

• Allocating funds based on students and student characteristics: “Staffing expectations, cost reimbursements, or other input requirements constrain decisions for rural communities.”

• Eliminating specifications around service delivery: “Allowing these districts to create service delivery structures that take into account local schedule preferences and maximize locally available resources may provide a higher ROI.”

• Promoting shared services across districts, instead of consolidation: “Consolidating rural districts may impede a district’s ability to be innovative, nimble, and more highly productive.”

Infrastructure, Flexibility, and Training

“How Productivity Can Boost Productivity in Rural Schools” is from a panel of academics and other experts (including Gross and Jochim) about the different technology platforms that can help such rural districts, including virtual learning and online professional development.

Among other strategies for states, the panel recommends that they prioritize broadband Internet access, help start regional collaborations so that rural schools have economies of scale when it comes to technology, and ensure that virtual schools don’t get a pass on issues where traditional schools are subject to close scrutiny.

Noting how former Idaho Superintendent Tom Luna’s push to enhance technology didn’t go smoothly, the authors write: “Recognize that the state plays a limited but critical supporting role. While many smaller, rural districts appreciate state support, universal mandates are less likely to be responsive to local needs and can become a political lighting rod.”

Meeting Unique Needs

The final essay in the compilation deals with how rural schools can better assist students with special needs. “How States Can Help Rural LEAs Meet the Needs of Special Populations,” by Tessie Rose Bailey of Montana State University and Rebecca Zumeta of the American Institutes for Research, notes research indicating that half of administrators for rural schools report challenges in hiring teachers to work with such students, and how those students in turn rarely get instructional services tailored to their specific needs.

And the funding set-up from both the federal government and states doesn’t give rural schools a lot of freedom, Bailey and Zumeta wrote: “For example, [a local education agency] may find itself with six new ELL students with no immediate funding or resources to provide those services. Low incidences of special populations can also limit access to state programs and funds, especially when SEAs require a minimum number of students in order to qualify.”

Here are a few suggestions Bailey and Zumeta have for states:

• Ensure rural LEAs have access to alternative methods of service delivery for special populations: “Over the last decade, several states have piloted teletherapy programs for services delivered by speech language pathologists, occupational therapists, and physical therapists.”

• Ease the burden of compliance monitoring: “For example, SEAs could consolidate reporting requirements to simplify the process of reporting progress on multiple projects.”

• Support efforts to implement e-mentoring programs to retain quality teachers of special populations: “Supported by the Kansas State Department of Education, E-Mentoring for Student Success focuses on curbing attrition of new special education teachers by providing a matched mentor. The mentor and the rural teacher meet at least two times a week, and the mentor is always available via email.”

Read “Uncovering the Productivity Promise of Rural Education” in full below: