Although reaction to new international testing data has focused mostly on the middling performance overall of American 15-year-olds, the results also serve as a reminder that the United States is not exactly a world leader even in producing a cadre of top-tier performers in mathematics and science.

Only about 10 percent of U.S. students scored in the two highest achievement categories in math on the Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA, well short of the figures for a host of other nations, from South Korea and Japan to France, Germany, and New Zealand. In fact, the U.S. results were below the average for the 34 nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

In science, the U.S. position was more favorable, but not dramatically so. With 9.2 percent of American students meeting levels 5 or 6, the United States was about average among OECD nations, trailing more than a dozen PISA participants, including Finland, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, and South Korea.

At the top of the pack in math and science was Shanghai, China, one of a handful of non-national education systems that took part in the assessment in 2009. In math, for instance, about half of Shanghai students were in the two highest categories.

However, a variety of analysts caution that Shanghai is not representative of China as a whole; it’s widely seen as at the vanguard of that nation in terms of its educational performance.

The PISA results from December arrived months after the National Science Board—a prominent panel that advises both the White House and Congress—issued a report sounding an alarm that the United States is failing to sufficiently identify and nurture the next generation of high-achieving innovators in the STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and math—and that the situation puts at risk the nation’s long-term prosperity. (“Expert Panels Tackle Ways to Improve STEM Education,” Sept. 22, 2010.)

‘Disturbing Findings’

Some researchers say the latest PISA results reinforce concerns not only about how U.S. students fare on average, but about the nation’s relative share of top performers.

“In many ways, this is one of the most disturbing findings,” said Mark S. Schneider, a vice president at the Washington-based American Institutes of Research and a former commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics. “In the modern economy, you need a lot of well-trained, smart people to drive innovation, to drive creativity,” he said, “a cadre of highly trained and highly trainable people.”

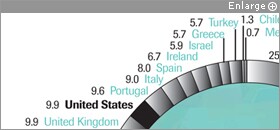

Percentage of students scoring at the two highest levels on the PISA mathematics exam among OECD nations

SOURCE: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

Eric A. Hanushek, an economist at Stanford University, also expressed concern about the data on high achievers, noting that while the United States has traditionally attracted plenty of talent from abroad to fill the gap, it’s getting harder to do.

“Historically, we’ve been able to import a lot of people to be our [engineers and scientists], but some of these people go back to their own countries now,” he said. “The competition for highly skilled workers has become much more intense.”

The one bright spot appears to be reading, where the proportion of American students reaching the two highest achievement levels on PISA—9.9 percent—beat the OECD average of 7.6 percent.

PISA compares the performance of U.S. 15-year-olds in reading, math, and science literacy against their peers internationally. In all, 34 OECD nations and 26 other countries took part this year, as well as several other education systems, including Shanghai and Hong Kong.

The assessment seeks to gauge what young people have learned both inside and outside school and how well they apply that knowledge in real-world contexts. The results are scored on a scale of 1 to 1,000. This was the fourth assessment cycle since 2000.

Overall in the latest round of PISA, American students’ science performance climbed to the OECD average. The U.S. score of 502 increased from 489 in 2006, not measurably different from the OECD average of 501. At the top in science among the OECD nations were Finland, Japan, and South Korea.

In math, despite gains from the last round of testing in 2006, U.S. students, with a median score of 487, remained below the OECD average of 496. In all, 17 OECD nations had statistically higher scores. The top-three scorers among OECD countries were South Korea, Finland, and Switzerland.

Finally, in reading—the subject that received more in-depth focus this time—U.S. achievement was roughly flat, at 500, compared with previous testing rounds, and about average among the OECD nations.

Out-Educated?

“The PISA results, to be brutally honest, show that a host of developed nations are out-educating us,” U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said the day the results came out.

Mr. Duncan noted that 15-year-olds in Finland and South Korea on average were one to two years ahead of their American peers in math and science.

On PISA, students are generally ranked into one of six categories based on their level of proficiency. In science, students rated at level 5, the second-highest category, can identify the scientific concepts of many complex life situations; apply scientific concepts and knowledge about science to those situations; and can compare, select, and evaluate appropriate scientific evidence for responding to life situations, according to an OECD document. In math, students at level 5 can develop and work with mathematical models in complex situations, identifying constraints and specifying assumptions, the document says. They can select, compare, and evaluate appropriate problem-solving strategies for dealing with complex problems.

In math, the 9.9 percent of U.S. students at level 5 or higher compared with 35.6 percent in Singapore, 25.5 percent in South Korea, and 21.6 percent in Finland.

In science, the 9.2 percent of U.S. students who at least reached level 5 compared with 19.9 percent in Singapore, 18.7 percent in Finland, and 17 percent in Japan.