As part of an education co-op, teacher Jim Lawlor travels Kansas' highways to serve students with disabilities.

Jim Lawlor eyeballs the clock and nudges the accelerator of the Chevy Blazer. The SUV lurches forward, the roaring wind rocking the vehicle as it hurtles down a skinny strip of blacktop that appears to lead nowhere. Suddenly, the hidden sun yawns, bathing fields of winter wheat in a gentle pink haze.

“Gotta put on sunglasses to protect [against] the cataracts,” Lawlor says, donning a pair of mirrored shades to shield his blue eyes. “In my line of work, you pay attention to that.”

Between the hours of 7 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. today, the peripatologist will log 300 miles on Kansas’ highways. He’ll stop at five separate spots to meet with five students with disabilities who attend schools sprawled across the prairie, and teach them to navigate their worlds with the help of white canes, wheelchairs, and walkers.

Lawlor, 50, expects this to be one of his easy days. On others, he bids farewell to his wife, Liz, as early as 4:45 a.m. Each month, he drives 8,000 miles to reach approximately 45 students living in 27 different communities throughout the state.

The instructor is one of 1,700 professionals shared by school districts across Kansas as part of an unusual arrangement that attempts to minimize the high cost of special education services and maximize efficiency. Twenty-four years ago, 259 of the state’s 303 districts formed regional partnerships and set up independent school districts, called cooperatives, designed to serve as common pools of special education personnel to meet the demands of federal law.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, up for reauthorization this year, requires states to provide a “free, appropriate” public education for the nation’s 6 million students with disabilities.

Sharing staff members makes sense in a largely rural state like Kansas, says Keith Reimer, the director of the Southwest Kansas Area Cooperative 613, the oldest and geographically largest cooperative in the state. There simply is not enough work to employ full-time specialists in every school, nor do districts have the money to do so.

The idea is popular, adds Richard W. Mainzer, an associate director of the Arlington, Va.-based Council for Exceptional Children. Districts in about 25 other states have also banded together to form cooperatives to provide special education services. Today, 39 cooperatives operate in Kansas, state officials report. Participating districts pay for services on a per-pupil basis as well as an annual fee of $10,000, which entitles them to an array of offerings.

“We couldn’t afford special education without this,” says John Dunn, the superintendent of the 300- student Macksville district in central Kansas.

Despite the long hours and lengthy drives in what passes for a portable office, Jim Lawlor loves his work. The Blazer is surprisingly tidy for someone who spends 60 percent of his day on the road. A cellphone is hooked to the sport utility vehicle’s dashboard, three or four bulky walking aids are loaded into the cargo space, and a cooler, stuffed with an array of beverages, rides in the back seat.

“Yes, we’re going to be right on time,” Lawlor says, gripping the wheel tightly.

|

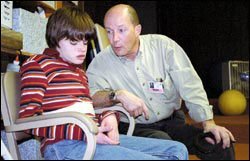

The mobility specialist explain’s the day’s lesson to Darcy Aves Macksville High, Macksville. Lawlor and the 18-year-old have been working together since she was 2. |

He is nearly obsessive about the ever-ticking clock on the dash. Having only about 45 minutes to spend with each student, he knows he must arrive precisely on time and engage the children as quickly as possible. Lawlor’s charges see him only twice a month under his tight schedule, which compels him to traverse the interior of the state as well as the borders along Nebraska, Colorado, and Oklahoma.

“I live my life at 65 miles per hour,” he says, noting that he’s never stayed overnight in a hotel and remains undaunted by adverse weather. In this part of the High Plains, that mostly means battling extreme winds or dirt storms.

Lawlor’s schedule is, in fact, about as hectic as it might have been if he had stayed in the suburbs of New York City, where he grew up.

The peripatologist—a specialization in teaching those with physical disabilities to be mobile—was the first “floater” hired by Cooperative 613 in 1977. At the time, the newly minted Boston College graduate was the only such specialist in the state; he guesses there are still fewer than 10 in Kansas today.

“I just hated the thought of going into New York City every day,” he recalls. “I don’t like to have people on top of me all the time.”

|

When the offer came from Kansas, Lawlor moved to a wind-swept farm and adopted a German shepherd who traveled with him to schools for years until she became sick.

Lawlor puts up with the relentless demands of the road, he says, because he has a heart for kids, though he has none of his own. “We’re only as strong as our weakest among us,” he says.

The small man in the leather jacket knows what it is to flounder. Stricken with polio as a toddler, he has never been able to run or even walk quickly.

“They told my folks I’d never get out of bed,” he says, his left leg visibly bowed. “Now, I’m providing a service that was provided to me.”

Not that his pupils articulate their thanks.

“The only people who don’t appreciate me are the kids,” he says. “I make their stigma present and hand them a white cane and say, ‘Now you’re different.’ ”

Lawlor pulls into the parking lot of Felton Middle School in Hays and unloads what he calls the “rockin’ ‘n’ rollin’ monster red,” a white cane with an enormous ball at the tip that permits the visually impaired to feel for obstacles.

Raylynn Lumpkin, 13, is not impressed. Ask her if she likes working with a cane, and she shakes her blond head “no.”

|

Lawlor sighs. He knows the cane represents independence. Without knowing how to get around in their communities by themselves, many students raised on isolated farms would not be able to understand the layout of a small town or of a city like Topeka, where they are more likely to find jobs. With their families tied to agriculture, Lawlor knows they’ll likely be alone in the city or stuck on the farm reliant on aging parents.

Raylynn’s special education teacher, DiRae Boyd, assures Lawlor the girl is making some progress. The peripatologist has taught Boyd how to reinforce his lessons between visits.

“I really rely on him,” she says. “I don’t have that kind of expertise.”

Lawlor bids Boyd and Raylynn farewell, and he heads back into the SUV with its ticking clock. He spins over to a nearby high school, pops his head into a classroom, and exchanges jokes with a student he only occasionally teaches before racing back out to the vehicle.

An hour later, he arrives at Eisenhower Elementary School in Great Bend.

Lawlor hustles 9-year-old Johnny Raat and his white cane out the front door for a lesson on directions. Nancy Meeks, a vision consultant also employed by the cooperative, trails behind them listening. She, too, is learning Lawlor’s techniques in an attempt to reinforce the skills he tries to impart.

Today, Raat struggles with Lawlor’s review questions. Meeks attributes the child’s difficulties to the fact that the pair can’t get together more than twice a month.

“He has too many other students to come more frequently,” she says of Lawlor.

Meeks herself does a lot of “windshield time,” traveling between 450 and 500 miles per week. Last year, she logged 750 miles weekly, but is no longer required to do so.

“I just felt so stretched,” Meeks says. She spent so much time on the road, she had difficulty fitting in both time to teach and to meet with classroom teachers, as the IDEA requires.

Lawlor escorts Raat back to the school and asks Meeks to join him for a fast-food lunch. Twenty-five minutes later, he’s back on the road bound for Macksville, where Darcy Aves, 18, waits for him 35 minutes away.

Upon arriving, the peripatologist makes adjustments to the girl’s walker, inadvertently receiving a rare grin from her. After working together for 16 years, teacher and student are almost family. Still, Lawlor administers tough love as he props her up on the walker and ushers her out the door for a trip down the school hall.

“I am not doing it; you do it,” he says, his hands placed firmly on her hips to afford her support. “It won’t happen if you don’t do it.”

She shuffles slowly. Right. Left. Right. Left.

“He is the reason my daughter is walking,” says Faye Aves, her mother.

Other floaters, however, haven’t been so dedicated. They are so busy or get so burned out, they don’t even bother to call and introduce themselves, Darcy’s mother says. Turnover is high in some of the jobs in the cooperative, she adds.

That’s one reason some don’t fully endorse cooperatives.

Critics also charge that cooperatives aren’t the cheapest way to do things. For-profit agencies, they say, could provide even less expensive services. What’s more, many dislike the way services are dispensed in Kansas’ more urban areas, where students with similar disabilities travel great distances to be grouped into one school.

“There are cooperatives that are wonderful, and others that are at the very end of the spectrum,” says Connie Zienkewicz, the executive director of Families Together, a Wichita-based nonprofit group that provides information about special education. “It depends on who is running the show.”

Dunn, the Macksville superintendent, says he gets a good bang for the buck: For $78,000, his schools this year receive the services of three full-time special education teachers, another part-timer, several paraprofessionals, and a mobility specialist, as well as physical, occupational, and speech therapists. They help about 40 students.

Wayne Sailor, a teacher-educator at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, says school districts could save even more money by employing distance education and contracting with private agencies.

The suggestion seems to annoy Lawlor, who contends students like Raylynn Lumpkin, Johnny Raat, and Darcy Aves need hands-on help. Services for children with special needs are expensive no matter who arranges them, he points out.

Though usually affable, Lawlor is not immune to the stresses of the job. An hour after he leaves Darcy Aves, he is in Larned, negotiating a neighborhood with Sarah Peterson, who attends the middle school there. He asks the 6th grader to find her way back to school, then realizes he’s made a mistake. There’s no road where he expected one to be, and he’s misdirected the girl.

‘If I didn't do this, they'd get service maybe one time a month or one time every three months.’

He shakes his head and adjusts the mirrored sunglasses. He knows he’s supposed to have memorized the physical layouts of the towns he visits, yet he’s responsible for children in so many places, he can’t always remember the towns.

Lawlor quickens his pace back to the SUV.

“When I started out, I came every week, but the number of kids has tripled,” Lawlor says later, adding that modern medicine and more accurate diagnoses produce more children with special needs.

Could he take on fewer students?

“If I didn’t do this, they’d get service maybe one time a month or one time every three months,” he says.

The late-afternoon light is growing purple. Lawlor guns the engine of the Chevy. “My wife,” he says with a smile as he zips down the highway, “is making fish stew tonight.”