Today’s Guest post is written by international Formative Assessment expert Shirley Clarke. Clarke is located in London, England.

My passion is the practical application of the principles of formative assessment - working with action research teams across the UK and the US to experiment with ways in which we can maximize student achievement. Formative assessment, through its unfortunate mislabeling, has sometimes been misunderstood to be continuous summative action or something a teacher does to students to get information.

Formative assessment is, in fact, a number of elements which enable rather than measure progress, and result in students becoming assessment literate. These are:

- A learning culture of a growth mindset (Carol Dweck) and meta cognition or learning ‘powers’ (Guy Claxton)

- Involving students in planning units of work

- Effective talk and discussion

- Effective questioning

- Knowing lesson learning targets (confusingly called lesson learning objectives in the UK) and co-constructing success criteria

- Knowing what excellence looks like

- Effective ongoing self/peer and teacher feedback

Let’s take one of these - the use of fantastic questions at beginnings of lessons, engaging students instantly in the subject matter and establishing prior knowledge.

Many teachers start lessons with recall questions and a culture of ‘hands up’, during which many students opt out. Once talk partners are established (my research shows that randomly paired talk partners which change weekly are most effective), the ‘hands up’ can go, because every question to the class is followed by a very brief discussion with the talk partner. Named popsicle sticks out of a can are used to determine which pair then answer, thus providing maximum focus. Unlike the ‘hands up’ scenario, every student has to talk and think.

Recall questions are often our default, so one aspect of my work has been finding brilliant question templates which can be used for any subject or age group. These can effectively convert recall questions into highly worthwhile questions which will deepen and further student understanding rather than simply measuring it, providing the perfect lesson start.

So far, I have gathered at least 10 templates, the most popular of which are:

- A range of answers

- A statement

- Right and wrong

- What went wrong?

- Starting from the end

- Odd one out

- Opposing standpoint

- Order these

- Always, sometimes, never true?

- Real life question

Remember that all of these strategies have most impact when talk partners are asked to discuss their thinking first, rather than as whole class. Let’s take a look at some of them...

A range of ‘answers’

Notice the juxtaposition of ‘answers’ which are right, wrong and ‘maybe’. The more ambiguous planned ‘answers’ promote the most fruitful discussion between talk partners. For young children pictures are used.

The statement

The question here is whether the students agree or disagree with the statement, after short paired talk, giving their reasons. This technique can be used across all subjects. This table shows a traditional recall question converted into a richer statement for discussion:

One teacher in a Scottish school showed her class a picture of a Viking and asked ‘This picture shows a Viking. Do you agree or disagree?’ Those who agreed gave reasons such as ‘His badge has a Viking sign on it'/'He is wearing a cape’ and ‘He has a scruffy beard’. Those who disagreed said, ‘He is not wearing a helmet. All Vikings wear helmets!'/ ‘He doesn’t have a sporran.'/ ‘He has the wrong sword’. At the beginning of a lesson on Vikings, students’ prior knowledge and misconceptions were quickly revealed.

The statement can also become ‘Is it always, sometimes or never true?’ such as in

- Multiples of 3 are odd numbers

- Odd numbers multiplied by even numbers have odd answers

- The heavier the car, the faster it will travel down the ramp.

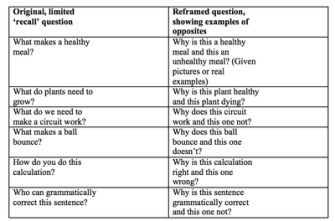

Opposites, or one that works and one that doesn’t

Being presented with right and wrong answers appears to give children more prompts, odeling and opportunity for thinking and discussion than simply being asked to work something out from scratch. Some examples:

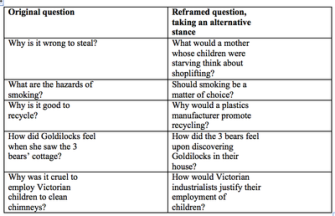

The opposing standpoint

This is a very effective strategy for discussing PSHE issues. Notice that the original questions are actually good questions, but follow expected and conventional thinking. The reframed questions force children to think of issues from an unconventional standpoint. Some examples:

Instead of asking ‘How did Cinderella feel about her stepmother?’ one teacher asked ‘How could Cinderella have helped her stepmother become a better person? ' One usually low achieving student commented:

'Cinderella didn't really think much about herself. She needed to stand up for herself. She just took it. She should have told her she was upset with her. The stepmother probably needed someone to stand up to here to stop her from being silly. She could have given her more friendship tokens or told her she loved her. Then her stepmother wouldn't have been jealous and might have liked her.'

‘Odd one out’ and ‘What went wrong?’

Both of these strategies link particularly well with mathematics. I watched a teacher start a lesson on equivalent fractions, asking which was the odd one out between 1/3, 25/50, 1/2 or 50/100. Their responses on whiteboards showed that 2 children didn’t understand, who were immediately asked to chat to their talk partner to see why they got two different answers.

For a lesson on properties of 2D shapes, ‘Which of these shapes is the odd one out? How many different answers can you find?’ produced a wealth of ideas and clear indication of which properties students already knew.

Using old pupil work to start a lesson with the question ‘Where did they go wrong?’ demands that students analyze and deconstruct, thus demonstrating their knowledge but also helping them reconstruct it. After learning about multiplication grids, one teacher asked the class what had gone wrong here:

The mistake is not obvious, which means some thinking has to take place....

The teacher from my second DVD presents his students with success criteria and an incorrect calculation for them to deconstruct.

So what did elementary students think about these questions?

'I like it when we have a question like this as it does make me think and you have to explain it. It is really challenging!' 'I think that answering 'right or wrong' questions is good, because it helps us to think more and we are able to argue against one another. "I think questions are good because they give us something to think about and give us time to think and I also like that we hear what other people think.' 'We get time to talk. The lazy people have to give an answer. It doesn't get boring for us."

For more information regarding Shirley’s latest book ‘Outstanding Formative Assessment’ and DVDs of teachers in action, please click here.

For more information about Shirley Clarke, please click here.