As schools try to make up for lost learning from the pandemic-related closures last spring, every missed school day is a step backward. School and district leaders have seen wildly different guidance from states when it comes to balancing the need to make sure students attend school and limiting the potential for sick students to spread the coronavirus among classmates and teachers.

New research suggests that setting up systems that allow schools of different sizes and grade levels to quickly adapt to changing community infection rates can be vital for not only preventing outbreaks, but also keeping attendance more consistent for students.

The research group Mathematica used data from Pennsylvania schools to run some 400,000 simulations, using different levels of community spread of the virus, different sizes and grade levels of schools, and different approaches to remote or in-person instruction and quarantine for potential outbreaks.

For community infection rates, the researchers ran five different simulations, from as low as 10 per 100,000 people each week to as high as 175 per 100,000 each week. That’s because studies have suggested, based on the number of people who carry COVID-19 without symptoms, that true infection rates in a school or community can be about five times as high as the positive cases counted.

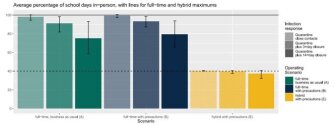

The Mathematica study found that while schools that used full-time, in-person classes could reduce infections by instituting schoolwide three- or 14-day shutdowns, these approaches tended to be more disruptive and result in more overall absenteeism than using a hybrid remote schooling model from the start, coupled with preventative health measures and rigorous contact tracing and quarantine for students and staff who tested positive for the coronavirus.

“There’s no way any school can guarantee zero infections because the school doesn’t control what kids and staff and families are doing outside of school,” said Brian Gill, the lead researcher for the study. “And so the question is, can you operate in a way that reduces the additional infections being spread in the school? The good news is that the modeling suggests that there are ways to dramatically reduce any additional spread of infections in school.”

Using health precautions including mandatory mask-wearing, keeping six-foot social distancing, and preventing students from mixing together outside of their classrooms together significantly slowed the spread of infections. “And when you combined precautions with part-time hybrid operations in small groups,” Gill said, “it is likely that most infections brought into the school will not lead to any additional transmission within the school.”

The study found part-time hybrid schooling kept outbreaks lower and school attendance higher at all community infection levels. Hybrid models reduced the number of contacts that any individual student had, reduced the amount of time students spent with others while in school, and reduced group sizes enough to allow better social distancing within classrooms.

Beyond ‘Rules of Thumb’

The results come as school districts grapple with how to translate public health and contact-tracing guidelines into classroom practices, at times leading to confusion. Iowa, for example, follows a common rule of thumb in identifying that anyone who came within six feet of someone infected with the novel coronavirus for 15 minutes or more as being at high risk of exposure themselves. These are the people generally asked to self-quarantine. But in the wake of a dramatic jump in school COVID-19 cases recently, educators have reported being told to ask students to get up and move around every 12 to 14 minutes in an effort to keep them from being close to any given student for 15 minutes.

But there’s no reset button on COVID-19 exposure; there’s simply a certain amount of risk in being near a person who has the virus for any length of time, and that risk goes up the closer you are and the longer you stay in contact. In fact, there’s some evidence that moving students around a poorly ventilated room every 10 minutes could actually increase the number of students they are exposed to over the course of a school day, thus upping their overall risk of infection.

“I don’t think it would be wise to make an assumption that there’s some magic 15 minutes,” before someone could become infected, Gill said. “There’s no good evidence” that having students move every few minutes would reduce their risk of infection.Rather, the study found that hybrid-model schools that rigorously traced and quarantined students who had been in contact with those who were positive for coronavirus were able to significantly reduce infections without needing to use the more disruptive three- or six-day schoolwide closures.

“The districts that are really on top of mitigation are really working on preventing spread instead of being reactive,” said Sara Anne Willette, a data analyst who tracks school COVID-19 cases in Iowa, but who was not involved with the Mathematica study.

In fact, the trade-offs between time and number of contacts led to at least one surprising finding: The Mathematica study found comparatively little health benefit to using full-time in-person instruction with block scheduling or “pods” for all students; while students had fewer contacts, they still stayed in relatively larger groups for longer periods of time.

Matthew Stem, deputy secretary for elementary and secondary education at the Pennsylvania education department, said his state plans to use the Mathematica research to help districts evaluate and adapt their protocols for responding to the pandemic as it evolves. The state required its districts to develop multiple re-opening plans for in-person and remote schooling.

“We do see significant variation across counties and across the Commonwealth, and on the strategies being employed by school districts related to instructional models,” Stem said. “Our district leaders almost universally have multiple plans, not only for how they were going to reopen, but how they would pivot to a more restrictive or conservative approach depending on changing conditions in community spread.”

Chart Source: Mathematica